Under a mid-morning sun Andrew Lacrosse parked his bent worn orange pick-up, rust eaten all along the bottom, in front of forty-six year old Trudy Bell’s small log home and gave the horn two sharp taps. It was two weeks since his wife died. Through the kitchen window with the open curtains lifting and rolling gently she watched his truck stop and froze hoping he’d quickly move on when she didn’t go out but he shut the engine off.

She resumed cleaning dishes watching him wait in the shade of his truck with no intention of obeying his summons. The truck roof hid the top of his head, a thick meaty wrist darkened with grime rested over the steering wheel and the other arm was relaxed on the door. Tall poplars bloomed full and a warm wind made them noisy and she had loved the day expecting her younger sister. Looking at Andrew changed everything. He turned his hand to look at his watch, honked quickly two more times and she felt outrage and pushed the window down and pulled the curtains shut.

Trudy mostly Ojibway and the remaining quarter or so French and Scottish of indeterminate proportion, is unusually tall, six two. She’s taller than all the men of Suspan, Ontario and her tallness seems to emphasize a natural dignity that most sensible people recognize immediately. Her long black hair, parted in the middle falls shiny and straight to her waist and her very dark almost black eyes are serious and thoughtful, radiating intense life through a soft sheen of knowing and far off sorrow. Four years ago she was widowed when her husband’s boat overturned crossing Big Magi Lake during a cold October storm. Like a lot of trappers he couldn’t swim and didn’t wear a life jacket. She remained in the small railway junction town she knew most of her life that never had a hospital, big supermarket or police. A couple hard years passed and when the pain and loneliness subsided she grew content to live a peaceable life without remarrying.

For three years Andrew rented a house a couple hundred meters from her down a gravel road separated by four weathered homes on spacious lots each with two or more derelict pick-ups like stranded ships in long grass and long dirt driveways. Before his wife’s illness, Trudy and most others in Suspan hadn’t been in the reclusive couple’s home. Helen Lacrosse, a stranger to the town like her husband, had had a polite curt manner, seldom smiling or offering anything beyond what was needed to get by in her dealings with people. Trudy always thought she seemed lonely and her cranky isolation had been created by circumstances that likely rested with Andrew. She thought there was something restrained and hidden behind his reclusive quiet sullenness.

When Helen became ill Trudy felt compassion and with a few other women started routinely visiting, entering the strange gloom of their home bringing casseroles, helping with laundry and cleaning. It was clear Andrew helped her through the illness. Trudy often found him supporting her with her arm over his broad shoulders and his strong calloused hand tenderly guiding on her waist making their way carefully to the toilet or to settle on the couch. He’d cover her with a blanket and did what she asked without the slightest hesitation. But he was quiet when the women visited and never joined them. He’d sit at a small table out of site, expressionless, in the small blue kitchen with crooked blue cupboard doors and silver scalloped handles.

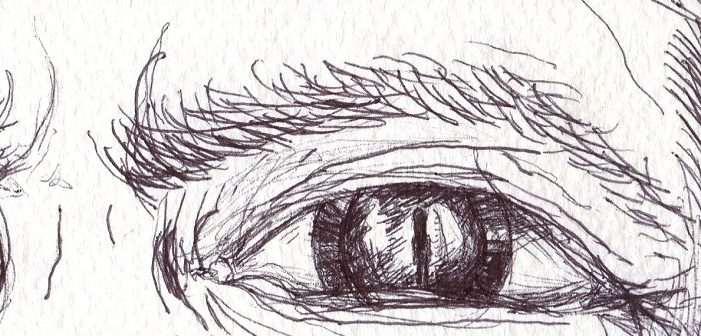

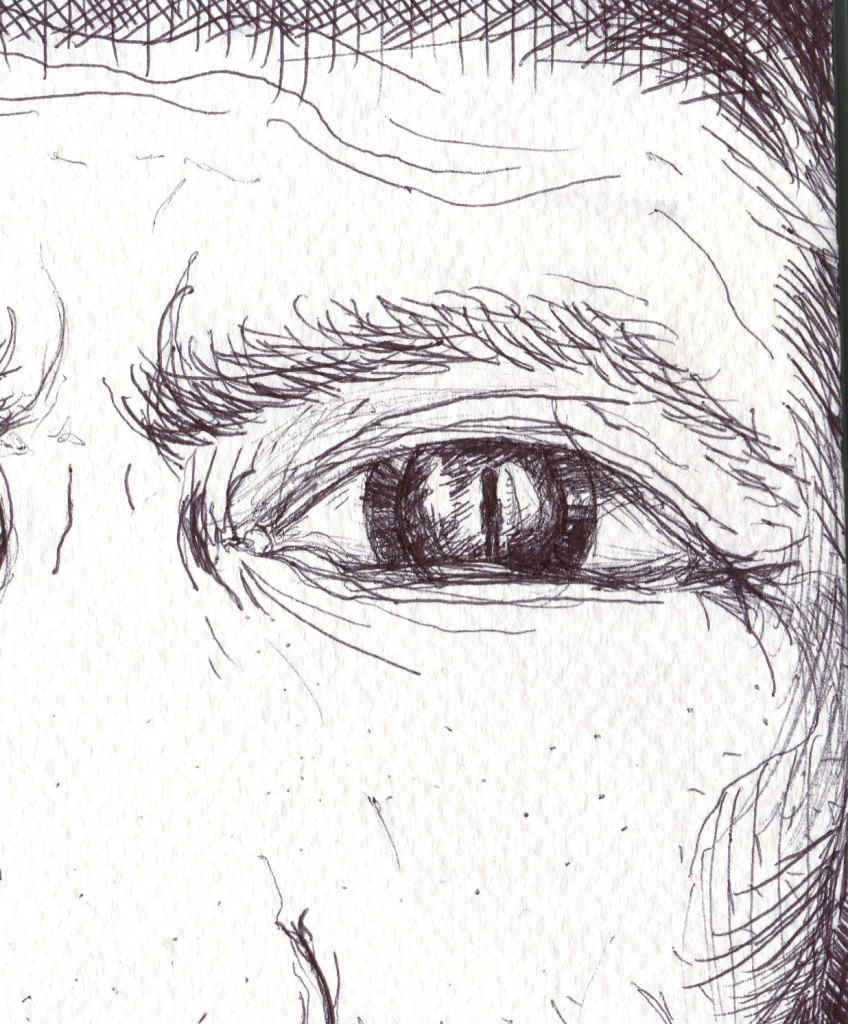

Helen wouldn’t remain in hospital after her treatments and with iron-will fierceness demanded to be home as long as possible. Andrew quietly and obediently obliged until it was just too close to the end. For her final trip to Edison he had put her on a mattress in the back of the pick-up unable to sit up, more unconscious than conscious, and rattled slowly ninety-three kilometers over a potted road. Afterward, all the women who tended her said there were times they felt uneasy around him. He looked unnatural, dark, brooding in the strange blueness with the lights out and kitchen curtains drawn closed muting the sunlight. From under his cap peak there seemed to be a dark band around his small green eyes that never settled on you, almost always in the kitchen out of view from Helen on the living room couch, and it seemed to Trudy he was waiting.

He’s not a bad man, Helen had told her looking to the kitchen with tenderness as if she knew what Trudy was thinking. It’s just his way.

Two weeks before that final trip, during a sunny morning just as the tree buds were opening Trudy went to their home. From the table he had looked up at her full in the face, staring uninhibited from under the long cap peek as she came through the door with the brightness of the day behind her shining into the blue gloom of the kitchen. In the revealing light fine details of his broad shiny smooth face were visible and she shuddered. His eyes looked yellowed, corrupted, sick with desire and he smiled to himself as if affirming something he’d been mulling over, something that didn’t belong in the light of the sun. He probably wasn’t even aware he smiled that revealing smile that seemed to possess some illicit promise to himself and a wave of revulsion passed through her. She had seen that expression, that particular look on a man’s face before. It wasn’t like the obnoxious flirt empowered by drink or a man convinced he was in love with her and was emboldened to seek her affections (which for a time she’d seen plenty of after her husband died). It was something darker, born and grown in darkness and long contemplated, rising to the light and surfacing to a smile. A self-promising smile.

Pinching the curtain open and staying still she watched and he hit the horn sending two long impatient blasts into the warm wind. She looked around nervously wondering what to do if he came to the door then dialed her sister and he started the truck with a roar, grinding violently, lifting blowing dust in the warm morning glow. She put down the phone and was relieved to see her sister coming onto her sand packed walk a minute later.

“What’s wrong with that Andrew guy anyways? He’s crazy,” Trudy’s sister said coming into the kitchen with amazement.

“Why?” asked Trudy.

“He almost ran me over going full blast. I had to move quick.”

And Trudy kept to herself what had happened.

At three in the morning her eyes opened suddenly, fully alert like she hadn’t been sleeping. She put on a light blue house coat, tied it tight quick and walked quietly to the kitchen. Keeping the lights off, she leaned over the sink pulling the curtain back and looked out the window. Except for a few far off dull porch lights there was only star light making the tree line just visible. She watched for a long time imagining things moving in the darkness and was frustrated with herself. Though she didn’t see anything she took her husband’s old unused twelve gauge shot gun and a box of old shells from the closet, put a shell in the chamber and placed it beside the bed. She tried falling asleep again but thought she heard something in the long grass outside her window in the back yard. She got up quietly picking up the gun and stepped slowly in the dark, her body very straight, pressing firm and silent on the balls of her bare feet over the cool linoleum then the carpet until she was at the back door. She drew the spring hammer back with her thumb until it clicked, ready to be released with a light pull of the trigger and breathed deep and even. Holding the shot gun in front of her with the barrel down, she stood quiet listening. There was no wind and she heard clearly something moving in the grass. After a long silent moment, frozen in the darkness, she could just see the gray round metal door knob creak slowly left then right against the lock. She raised the gun to her shoulder, positioning the barrel where a man’s stomach would be, braced herself for the gun’s hard kick, and pulled the trigger. There was only a dull metallic click. The shells were very old. She watched paralyzed but the knob didn’t turn again and it was silent and she could feel her heart pattering and her chest rose and fell quick.

She didn’t sleep through the long night, rocking with all the lights on in a chair that had been her mother’s and unwanted memories from childhood emerged and took life. Memories long secured in forgetfulness freed themselves as if by their own accord to join the present fear and quiet outrage.

In the morning she was at the general store when the store-keep unlocked the door and bought a box of shells. She slept lightly into mid-afternoon, made a pot of coffee, and watched the day turn to dusk and when the sun was about to disappear into the forest horizon she loaded the shot gun with a fresh shell and rocked in her mother’s chair waiting for darkness.

*****

About the author: Glen Louttit was relocated from Thorold, Ontario at the tender age of 6 years old when his mother moved their family back to her home town in Northern Ontario. He grew up in Oba, Ontario where the population during his life time never exceeded eighty-five. It was shocking and beautiful and after a short time Glen forgot that he ever lived in southern Ontario. Always a writer, over the last two years Glen has written a collection of short fiction, most of it set in the North. Says the author, “I think some of these stories came out of a longing to be there. At fifty seven years old, living and working in the Sault, I look forward to retirement so I can go back.”