Much of Cree trapper Sam Samikee’s substance, from conscious into the unconscious and somewhere beyond, (where flesh and spirit are intricately and almost inexplicably fused) was bound to the undulating scrub laden boreal lowland of the vast Suspan Ontario Township. He trapped his allotted territory thoughtfully, working it with experience cured in time and a continuum of knowledge with half remembered or forgotten origins and a measure of myth. Looking at bark on a cedar, cut and peeled back with his old jack knife, he’d tell his wife, Emma, the mink would be leaving the area and wouldn’t be back for a long time and she’d look at him questioningly, wondering if he could really see such a thing and sometimes it angered her.

“How do you know that?” She’d demand and he’d look at her with a far-away expression unable to answer.

She had been sturdy and stout like him, breaking trails and managing the trap line without knowing a thing about reading cedar bark. For twenty-nine winters they had trapped together deep in the quiet snowy boreal in one of their small outpost cabins living mostly on moose, dried fish, potatoes, and bannock, drinking lots of sweet tea with powdered or canned milk. In snowy isolation, unhindered by the distraction of living among rancorous restless spirits they grew deeply content and became like one, knowing one another thoroughly and still loving. From the beginning it had been love but it was consummated, transformed and distilled by time and they didn’t need the reassurance of words. He only told her once he loved her. During their humble courtship thirty years ago sitting at her mother’s kitchen table with their earthy brown faces shining softly in muted yellow intimate light from an oil lamp’s steady flame he had looked up to her face and said shyly, “I think I must love you… I mean… I love you…that’s what I mean.”

“Me to,” she answered just as shy and in a darkened corner at the edge of the lamp’s glow, her mother had rocked in quiet approval.

They talked little compared to the manner of most other couples and bared their burdens happily. They often knew what the other was thinking and had a peculiar affection for humor. A joke could last days, weeks, years even. One fall, just before freeze up, beavers completely sealed a small creek culvert that flowed under a logging road. The water rose making a pond on one side eroding and flooding the road and as usual the logging company hired Sam to trap them. He and Emma drove there and a beaver was disturbing the still water, swimming boldly along the partly submerged scrub and stunted tamarack. Emma stepped out of the truck first into the crisp air taking the 22 automatic before Sam could. She shot quick making a straight sprite of water, missing, and the beaver dove with a snap of its tail. Sam stood beside her and they waited quietly watching the water. When it’s brown head surfaced she took two quick shots without hitting it and it dove and they didn’t see it again. She pointed the rifle down and looked at Sam beside her who was still looking quietly at the water and he turned to her and she watched it rising in his eyes and he held it back for just a bit then said, “That beaver had a good scare. He’ll go home and tell his wife I guess. Maybe they’ll have a good laugh too. He’ll say ‘It’s a good thing that woman can’t shoot straight’.”

The next afternoon he came home from setting the traps and there were three partridge on the table, each with a single neat shot to the head and she was standing at the stove drinking tea watching him. He sat and drank tea quietly with the birds before him and didn’t look at them once. The next night she made a savory partridge stew and they ate quietly and when he finished he looked up at her while she waited.

“That’s…that’s the best moose I ever had,” he said.

And it would keep going until the following autumn. He had got out of the truck with his rifle to take a beaver, brought the gun to his shoulder, pulled the trigger quick and it only made a dull click. He took out the clip and it was empty. He looked back to the truck and he could see the back of Emma’s head through the window. She hadn’t even turned around to watch it unfold, but unloading the gun on him completed the joke to her satisfaction.

But for the last two winters she remained at their home in Suspan, discontent, and pining while he went to their winter dwellings on his own and like her suffered loneliness. It came suddenly while piling fire wood like she’d always done and something gave in her back. Afterward the simplest movement could cause her to wince in pain and she’d have to find a chair while bent over holding her back. The only thing the doctor in Edison could offer was pills. Sometimes Sam drove his snow machine back to town without a practical reason and they’d spend a night together and her heart would jump when she’d hear the motor she knew well buzzing through the trees.

Then her knees started to weaken, becoming numb until she could only stand for a couple of hours at a time and needed to stretch them out for long periods. Sam would offer to rub them but it only annoyed her.

“You’re just trying to get fresh with me,” she joked in the way she always did without a smile but with laughing eyes.

Frequent urinating, weakness, and dizzy spells brought her back to Edison for tests and the doctor told her with all the gravity he could affect the seriousness of diabetes and showed her page after page of horrible pictures from a medical book of people (some of them native) who refused to manage it properly. Regardless, she wouldn’t consider denying herself bannock with wild raspberry jam or her sweet tea.

The last three months her lower legs and feet were often swollen making it hard to walk or stand very long and he made new steps and hand rails to put her weight on more easily. At the suggestion of the old Finnish store keep he bounced his old truck ninety kilometers over a poorly maintained dirt road to a furniture store in Edison bringing back a chair that heated and vibrated and he made her sit in it and she had laughed with playful scorn when he turned it on.

“I think this chair is for those weird people who like those shaky beds in the hotels. Maybe you’re trying to trick me,” she joked and Sam laughed inside and she could see by his eyes he laughed.

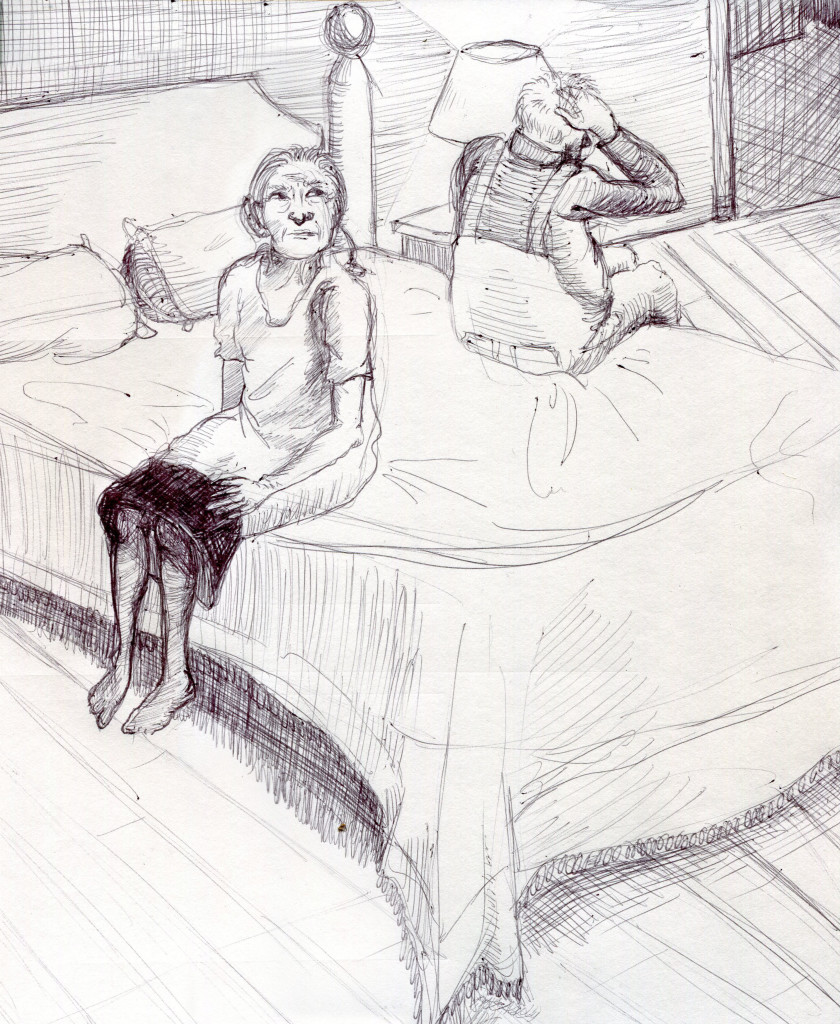

A warm summer set in and instead of working the fishing lodge he stayed in Suspan to tend to her. He listened to her moan quietly while she rubbed her bare legs sitting on the edge of the bed then tapped them lightly with open palms. He laid on his side over the blanket facing away in full body underwear. A small lamp on the dresser made a soft light and their shadows were big and hers was very big on the wall in front of him.

“Did you put Thunder out?” she asked. The husky would try to make himself small and stay out of site when it was time to go out.

“Yes”

“He’s got water?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t forget to pay the store bill tomorrow and pick up coffee.”

“Yes.”

She turned off the lamp and got under the covers slowly moving around over squeaking springs and settled facing away from him and their eyes were open in the dark.

“Sam?”

“Yes?”

“…I’m going to stay in Edison this winter.”

“…oh?”

“Ya. And I think I’m going soon, before the fall comes and stay there for good.”

“Oh?”

“It’s just too hard Sam.”

“…I can get one of those wheelchairs,” he said

“It’s too rough to stay here anymore. The hospitals there and Margret’s there. It’s better for me.”

He was quiet, not knowing what to say, troubled.

“Sam?”

“Yes?”

“When I go you should clean yourself up and go see Maureen.”

“Oh? …why?” he said confused.

“So you won’t be lonely. She’s got good strong legs and she needs a man too. I saw you looking at her once and she likes you too.”

He remained quiet unable to remember looking at Maureen in that way. That she wanted to live in Edison he could reason easy enough… but thinking she expected him to just take another woman shook him deeply. How could she not know how much he loved her, he thought. How could she say such a thing and he wanted to cry out in protest but kept quiet.

“She’s a good woman. She’ll take good care of you,” she said in the darkness.

“…I’m going with you.”

“…No…no…that’s no good. You can’t live in a big town…You won’t be happy if you leave the bush Sam. You won’t last,” she said like she’d been looking ahead for a long time.

He laid quietly, losing sense of time. His body seemed to dissolve into the darkness, to be part of it as if his consciousness was suspended in the darkness, and sadness came to him like an unwanted companion. He passed in and out of sleep but it didn’t feel like sleep and not quite like wakefulness and all the time the sadness deepening. And he dreamed; his dreaming mind suspended in an invisible almost weightless body, drifting over the still boreal deep in winter, drifting and gliding over frozen swamps through tamaracks and black spruce, over leafless poplars, rivers and white lonely lakes…and a voice calling…

He felt his shoulder being pushed over and over.

“Sam! Sam!”

“…wha…wha…what?” He said coming to wakefulness.

“Okay, you can come,” said Emma and turned over to go to sleep.

*****

About the author: Glen Louttit was relocated from Thorold, Ontario at the tender age of 6 years old when his mother moved their family back to her home town in Northern Ontario. He grew up in Oba, Ontario where the population during his life time never exceeded eighty-five. It was shocking and beautiful and after a short time Glen forgot that he ever lived in southern Ontario. Always a writer, over the last two years Glen has written a collection of short fiction, most of it set in the North. Says the author, “I think some of these stories came out of a longing to be there. At fifty seven years old, living and working in the Sault, I look forward to retirement so I can go back.”

For more stories by Glen Louttit click here.