George pulled the ropes tight over a thick worn canvas covering four months of supplies and tied them to metal loops on the side of a wood sled he built twenty-five years ago. When finished he was tired and leaned against it. It was just starting to get light and spruce, pines and cedars glowed blue with thick snow weighing their branches down and a full moon was high above them. He could see his wife in the lit window watching and he stood straight and went to the shed to get gas for the snow mobile. When he came out she was gone.

Still a couple a years left in the old ski-doo, he thought topping off the gas tank and went back to the shed.

He looked around before shutting off the light. There were rusted foot traps hanging on chains, snow shoes, skin stretchers, an old wood stove and a lots of junk he collected over the years. He felt tired again and sat on an old wood swivel chair he’d taken from the train station before they tore it down. He’d spent a lot of time sitting in it skinning beaver and martin and it was long worn through the thick varnish. Sometimes he just like to sit in it because it came from a time when he was young and strong, a time when trappers worked the land with knowledge. Many things changed since then. Twenty-five years ago he would have taken a dog team. Now they use a dog team just for prestige and attention.

His mind drifted over time to people and events and circled back to a familiar contemplation.

Damn him, he thought to himself. If he just waited for the ice to set right it would have been okay. Damn him. I tried to tell him.

It had never been right with him and his wife after their son died. She still cooked the same and took care of things at home. She was still a good skinner and could do many of the demanding jobs like chopping wood as well as he could. But she wasn’t there anymore. The pain had eaten away at the thing that gives life to a person’s eyes. She stopped hating him but it had been very bad for a long time.

He could remember the sound of snowmobiles climbing the hill to his home fifteen years ago and knew something terrible happened. They found the ice had been broken through and frozen over again. Through the clear ice and dark water they could just make out his son’s yellow snow mobile at the bottom of the Mawgi river.

“I didn’t want him to trap! Why? Why should he be a poor trapper? He should have gone to school! Not a damn trapper. You should have made him go. He’d be alive now. Damn you!” Lena had screamed hysterically with a Cree accent and threw herself on the bed and didn’t speak again for months. And when she spoke she wasn’t there anymore. And a deep loneliness grew and settled into him that he never knew before.

His powerful hands were gone. The last year he had to find ways of doing things around the weakness that was steadily growing.

“Maybe you should let it go this year George,” Randy said standing in front of the store watching him loading supplies onto his sled feeling pity for him. “Maybe it wouldn’t hurt to see a doctor George.”

“If I went to a doctor he might find something I guess. Or maybe he’d just tell me I was old.”

Through the open shed doorway he could see his wife looking through the window again. Her hair was long and still dark brown and the cabin looked beautiful set against the snow and the stars were still bright in the morning sky.

There’s enough wood for the spring. She’ll be fine.

He closed the door behind him and down the hill he could see the entire town of Suspan surrounded by dark wilderness. Smoke rose straight up from chimneys and only a few houses were lit.

No need to drive through town, he thought.

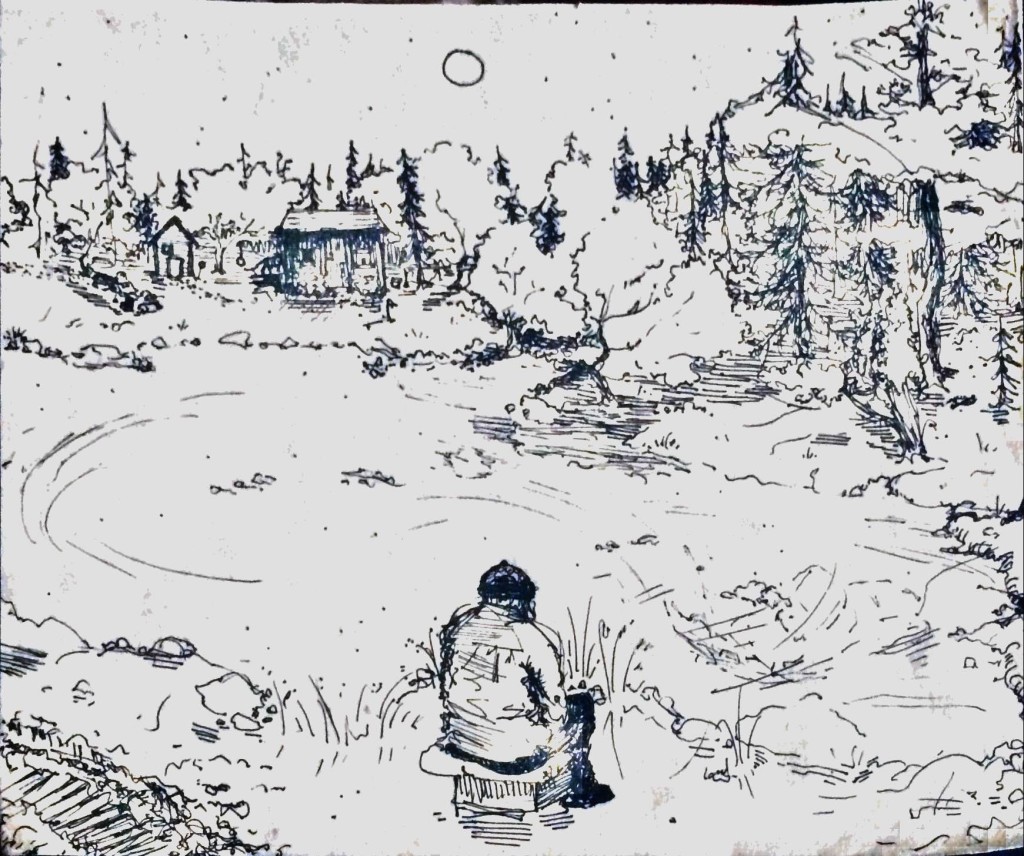

He sat on his snow machine, gripped the starting cord with his left hand, pulled hard as he could but wasn’t strong enough and had to get off the machine to pull with both hands. He put his mitts on and let the motor warm for a minute, looked to his house and his wife wasn’t in the window. He’d ride along the Mawgi until noon and instead of going east along the Albany River he planned go west to Kennedy Lake. He had a cabin there he hadn’t used since Lena stopped trapping with him.

She was standing in her night gown listening and could hear the snow machine idling. All week she watched him preparing to go out to the trap line and helped him quietly. She knew it was absurd but couldn’t stop herself from going through the motions. She knew he had nothing left inside. He could hardly lift a bag of flour. There was no way he would survive the winter trapping by himself. For many years she went with him but stopped after their son’s death. She listened to the engine pitch climb pulling against the heavy sled and the dark void inside her suddenly filled with profound anguish and the stubbornness of her spirit broke and the anguish surpassed that of her parents passing and the death of her son. She lunged to the front door and threw it open not noticing the cold air. She could see the trees lit by the snow machine light as it twisted along the trail.

“George!” She yelled as loud as she could and ran bare foot on the snow.

“George! Come back to me please.” And she was sobbing hard.

*****

About the author: Glen Louttit was relocated from Thorold, Ontario at the tender age of 6 years old when his mother moved their family back to her home town in Northern Ontario. He grew up in Oba, Ontario where the population during his life time never exceeded eighty-five. It was shocking and beautiful and after a short time Glen forgot that he ever lived in southern Ontario. Always a writer, over the last two years Glen has written a collection of short fiction, most of it set in the North. Says the author, “I think some of these stories came out of a longing to be there. At fifty seven years old, living and working in the Sault, I look forward to retirement so I can go back.”