Jason and Brian Stoavic, eight and seven, slim sun browned figures without shirts, stood still on the creek bank in a warming wind staring with wide eyes and hunter’s instincts into the cold rippling water. Each had cut and trimmed a poplar pole about nine feet and put a wire on the narrower end shaped in a circle fashioned to close tight when pulled against weight. They kept the tips of the poles with the open snares very still in the water so they wouldn’t disturb the fish when they came close. From behind them the high late morning sun took some of the reflection off the water and they could see clearly the shimmering stone creek bottom and everything that moved over it. Granny Stoavic told them, ‘get a big mess of suckers!’ for sucker patties and they had snared twelve and wanted a dozen more.

“A huge trout!” shouted Brian pointing excitedly.

“Calm down or you’ll scare him!”

Brian squatted low, moving the end of the pole slow in the water, following the trout’s motion, distorted and shimmering through glassy fibrous current. He stealthily moved the snare around the fish without touching it until it was just behind the pulsing gills then stood up fast, drawing hard and quick, twisting around at the same time pulling it from the water. His whole body shook violently, gripping the bending pole hard against the weight of the flopping glistening fish, spraying a spiraling pattern of cool sparkling drops, arcing it over him to thump onto the new slender grass.

“Granny’s gonna love that,” he said proudly.

Every few minutes small schools of spawning fish moved upstream, flitting their tails and drifting smooth, suspended in the current with their shadows moving over the stone and gravel bottom, propelled forward by instinct against the current and they’d scatter when one was pulled from the water and slowly drift back.

After an hour the boys were spent and happy, thoroughly smelling of fish with all they wanted. They threaded pieces of yellow nylon rope through the moving gills making four bundles that were very heavy when they lifted them. They labored through the dense scrub and tall budding poplars and came out of spotted sunlight into the full sun again on the river road. Their knees were bent and unsteady and the slimy tails gathered dirt and tiny pebbles from dragging on the road. A half mile away they could see the small logging town and the houses were small through trees and over a brown field with a green haze of young grass. When they were close to the railway tracks that marked the beginning of town they could see their home and in front of the general store a green truck hitched with a boat. The boys froze and watched the truck start to move.

“The game warden!” shouted Jason and ran off into the trees with his fish and Brian dropped his bundles in the middle of the road and followed. They crouched low behind fallen rotting black spruce in thick underbrush and watched.

“Why’d you do that?!” said Jason angry, looking at the fish on the road and was ready to dart and get them but the truck was already coming over the tracks.

“I didn’t mean to,” said Brian.

“Shit! They’re not suppose to be here till tomorrow. Oh shit here they come.”

The ministry truck bounced slow over the potted road stopping just before the two bundles of suckers with the big trout. Two conservation officers, dressed in brown uniforms with pistols in brown leather holsters on their waists stepped out and studied the fish scarred by snares.

“Come on now boys, I know you’re in there,” said the older taller one looking into the trees. He was well known to the people of Suspan, Ontario and considered easy going.

“It’s useless hiding. We know who you are,” snapped the young short slender one. The boys recognized him as the new warden from last spring. He had hid in the bush while it was still dark waiting until late afternoon in the damp cold at the creek determined to catch people snaring. But everyone knew he was there and a few teased him in that small town way he didn’t appreciate.

‘How’d you make out there warden. Catch any of those poachers. I hear they might be down closer to the river. Did you try there?’

The young warden tossed the fish in the back of the truck and stood at the edge of the road.

“We will come in there if you don’t come out!” he said scanning into the trees seeming to look directly at them and Brian started to get up. Jason pulled him back hard and put his finger to his lips sternly.

“You’re going to be in more trouble if we have to come and get you!” said the young warden impatiently and the men conferred quietly.

“They didn’t see us. They can’t prove it’s us,” whispered Jason harshly and Brian looked as if he was going to cry. “We don’t have to worry as long as we don’t get caught. He’s bluffing. There’s no way they’re coming in here.”

The men stood quiet for a moment then suddenly broke into a run off the road into the trees.

“Run!” Jason yelled and bolted up leaving the fish, running deeper into the forest but Brian wasn’t following him. He looked back through the trees and he was just standing and the small warden had him by the shoulder.

“I don’t want to go to jail!” Brian wailed and Jason kept running into the bush, splashing through the cold creek stumbling up the bank, deeper into the forest not stopping until he was panting then listened. It was quiet and the tops of the trees stirred just a little. When he heard the truck rattling back to town he made his way hidden in the trees until he could see his house and the green truck parked in front. From the shadows of black spruce and balsams he watched and the big warden came out first carrying a heavy sagging green plastic bag into the warm early afternoon looking around casually and the small one followed staring down at his notes. After they drove out of site he went into the house snapping the screen door shut behind him and sat at the kitchen table in wet soiled jeans, dirty and scratched. Stout granny Stoavic with a long gray ponytail over her fatty hunched back just continued stirring a pot not turning around then ladled stew into a bowl, took her cane and limped to him.

“They’re going down stream after they put the fish in Randy’s freezer,” she said glancing at him expressionless and put the bowl on the table. “They won’t be back for a couple days.”

“Where’s Brian?”

“In the bedroom…they took everything in the freezer. The little one figured there must be at least eighty fillets, but won’t know for sure until they thaw out. It was the little one that wanted to look in the freezer.”

He thickly buttered two slices of white bread and ate thoughtfully, coming to terms with his outlaw status, not looking forward to seeing his father. He went to his room and Brian was sitting on the edge of his bed shirtless flipping through an old truck magazine. Jason could see where a flow of tears had washed dirt from his tanned cheeks and dried.

“They said granny’s in trouble because it’s her house,” Brian said searching his brother’s face. “They took all the pickerel we caught. I didn’t tell them about the fish in the freezer, honest Jason.” And it looked like he was going to cry again.“What do you think dad’s gonna do when he gets home?”

“He’s gonna be mad for sure.”

At ten after five o’clock Andy Stoavic came home with his silver lunch pail and smacked it on the table.

“Where are the boys?”

“In the bedroom.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“What happened?”

She took a folded paper from between flowered porcelain canisters on the counter and gave it to him. He sat reading slow, rubbing his chin with his grime darkened hand and a dark band around his angry green eyes.

“Goddam it! Come on out here boys. Now!”

They stood before him not wanting to look up to his face.

“How in the hell?…you should know better. I told you they come early sometimes. What the hells wrong with you boys?”

“It Brian’s fault…” said Jason. “.. he dropped them and then…”

“It’s both your fault. Especially you Jason. You’re the oldest! Get back to your room. Both of you. Go!” he yelled stomping his foot and the boys ran into the bedroom.

“What’s done is done. Don’t go doing anything stupid Andy,” Jason heard his grandmother say.

It was after midnight and he couldn’t sleep. Without washing or changing from his work clothes his father had gone to the town’s only bar after supper and the house was dark and still. Across from him his brother was curled small under a heavy blanket sleeping. Looking up from his bed he could see the stars set in perfect darkness, dense and bright between opened curtains. He heard a pick-up and a bunch of boisterous men yelling and laughing and knew his father was with them. They bounced over the potted road past the house to the river and he was afraid. He imagined grim and violent possibilities, feeling the lonely cosmic anguish kids can suffer at the edge of impending disaster, at the mercy of adults who do or may do destructive and irrational things. He didn’t fall asleep until three in the morning and the men still hadn’t returned.

When he woke moisture on the window glistened with the sun just coming over the horizon and the house was cold. He put on a t-shirt, went to his fathers room and quietly opened the door just enough to peek in. He was sleeping very deep on his back over the covers still in his work clothes and boots with his mouth open. He went back to his room and Brian was sitting up rubbing his eyes.

“I think they did something bad to the game wardens,” said Jason.

“What?” Brian said looking at his brother blinking into wakefulness.

“Last night. I heard dad and a bunch of them going down to the river.”

“Is dad going to jail?” he said frightened.

“Ya. Probably.”

“Do you think they killed them?”

“…ya maybe.”

The warm May day didn’t pass in pleasant youthful idleness as it should have but instead with grim prolonged inertia. They were quiet, alert, staying close to the house, not seeing their friends or venturing the usual haunts. Andy Stoavic raised himself up, dirty and puffy eyed still in his work clothes in early afternoon with his perfunctory Saturday hangover and didn’t say much. He just sprawled with his legs raised, slouching in front of the TV in his easy chair drinking coffee with a familiar self absorbed gloominess like nothing was wrong, frequently pressing the remote. The boys were perplexed at his calm and frightened thinking he was probably a killer and avoided him. They even hid in the backyard when granny called out to them for supper, waiting until he finished so they wouldn’t have to sit with him.

“What’s gonna happen to us and granny when dad goes to jail?” said Brian reflecting sadly on the edge of his bed.

“I don’t know. Granny’s in trouble to. They’ll send us to a foster home in the city maybe.”

“I don’t want to live with strangers. I hate the city. Let’s run away!” said Brian ready to cry.

“We can go down river and make a place to hide until they stop looking for us.” said Jason as if he’d been thinking about it. “We just need an ax and fishing rods and…”

“Let’s do it Jason. Lets do it now!”

“We have to get things ready first. We have to do it so dad and granny don’t find out. Tomorrow’s best for sure. We can’t do it Monday ‘cus they’ll see us not in school and start looking right away.”

For the rest of the evening the boys secretly gathered what they thought necessary in pack sacks and hid them in the shed. Brian kept going back stuffing and re-stuffing as many comics and plastic action figures he could make fit with cans of food and half empty cereal boxes. Finally at the end of it all he determined an elf with a green frock and white sword was more important than canned peaches in syrup.

At breakfast granny Stoavic watched them curiously because they were too quiet and Jason blurted at her in a rigid scripted manner they’d be going to the sand pit and she frowned suspiciously. They went to the shed, put on winter coats, drew belts tight around their waists and helped each other mount the heavy pack sacks, somber and resolved. They’d planned a five mile hike west on the rail tracks to a metal beam bridge that crossed high over the Mawgi River. Then they’d go down into the bush along the river to a clearing Jason knew moose hunters used to tent.

“Are you sure you want to?”

“Ya. I’m sure. I’m sorry I messed up Jason.”

The windless blue sky morning was warming fast. They crossed a ditch up to the tracks and could see Matt Garson beyond a field on the river road with his fishing rod. He was in the same grade as Brian, always in a clean tucked shirt and neatly combed hair because his mother liked to fuss over him. He waved eagerly and yelled.

“Oh brother.” said Jason. “He’ll squeal on us for sure if he figures out were doing something.”

Matt bounced to them over the brown field with new slender grass.

“Hey, where you guys been and where you going with all that stuff?” he said studying them curiously. Their coats, much too heavy for the warming day, were drawn tight with belts, flaring below like ballet skirts above thin legs in worn jeans. Jason had a hatchet in his belt and Brian his father’s big sheathed bone handled hunting knife tucked in his.

“Just going fishing,” said Jason.

“What’s the hatchet for?”

“Just in case,” he said aware of the absurdity of his evasiveness.

“Are you suppose to be fishing after getting caught?” he said looking at the large frying pan dangling from Brian’s bulging backpack. “I don’t think you’re suppose to. What if the game wardens catch you?”

Brian and Jason looked at each other.

“They’re staying down stream for a couple days,” said Jason trying to appear natural.

“No they’re not. Didn’t you hear.”

“…hear what!?” said Brian, his voice rising with emotion.

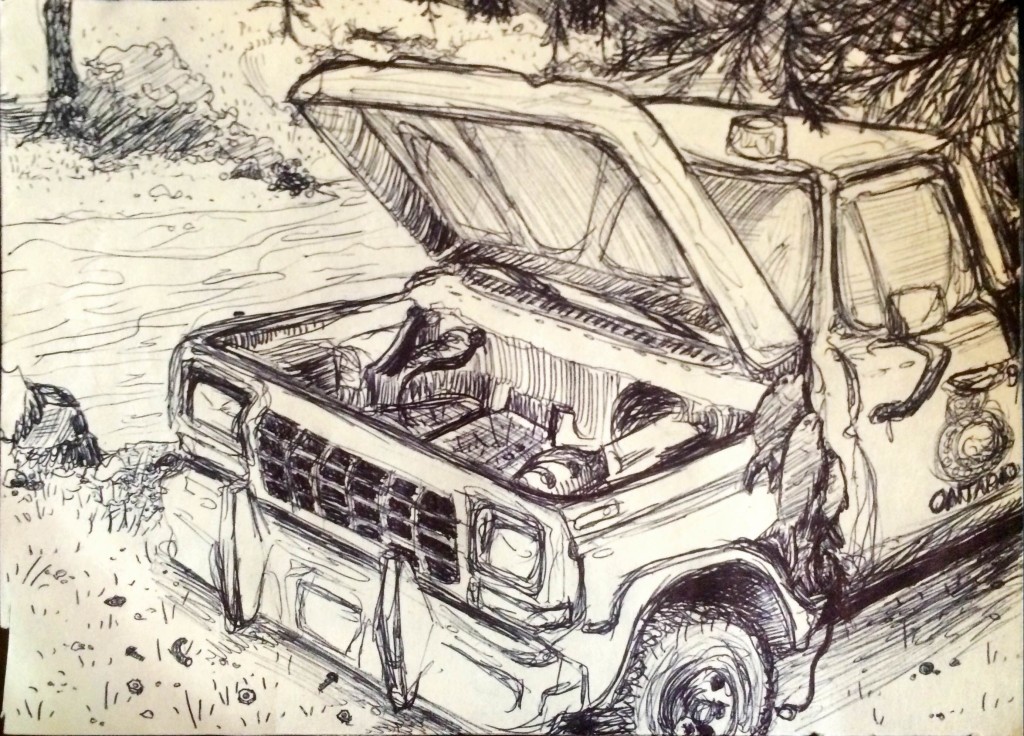

“They’re in the store right now. They walked up from the river just a while ago. They’re sure mad. They told Merrill someone took the engine right out of their truck. Said there’s gonna be alotta trouble. Took the engine straight out and put it on a palate with all the bolts and stuff all laid out neat.”

“In the store?….” said Brian incredulous.

“Yep. Lets go to the river and see it!” said Matt excited.

And Brian started crying and Jason told him to shut up.

“You guys sure have a lot of stuff for just fishing,” said Matt watching Brian curiously.

Jason wanted to laugh. He wanted to laugh hard but couldn’t. It felt like it was caught somewhere inside and couldn’t come out.

*****

About the author: Glen Louttit was relocated from Thorold, Ontario at the tender age of 6 years old when his mother moved their family back to her home town in Northern Ontario. He grew up in Oba, Ontario where the population during his life time never exceeded eighty-five. It was shocking and beautiful and after a short time Glen forgot that he ever lived in southern Ontario. Always a writer, over the last two years Glen has written a collection of short fiction, most of it set in the North. Says the author, “I think some of these stories came out of a longing to be there. At fifty seven years old, living and working in the Sault, I look forward to retirement so I can go back.”