Fine rain fell straight down and steady in late afternoon while Robert Mueller sat at his small desk with an open laptop. He’d drifted from the work he’d been doing since noon on a soon overdue paper for advanced macroeconomics and was gazing from his open second story dorm window to the courtyard below. He put his palms over his eyes pressing firm, trying to rub away the fatigue and eye strain then continued looking outside. Soft light permeated the overcast that covered the sky evenly and had an unusual hazy glow making the perfectly trimmed grass glisten and vibrant green. The cluster of dorms, with a plaque commemorating their completion and dedication in nineteen- thirty-eight, were red brick and perfectly preserved and every thing about the university was neat and proper.

Sounds of dorm life coursed through the long hall into his room -youthful optimistic chatter, doors opening and closing, banter, laughter, happy and restless, self-conscious and satisfied. He could have joined almost any of them and would’ve been readily accepted but it required more effort than working on a dreary essay. Natural relationships were difficult, more acting than enjoyment. It wasn’t arrogance or disdain. It was like he lacked what is inherent in others to be social. He was aware of his lack long ago and learned what people expected of him and was very good at playing his role. It helped he had a handsome face that conveyed trust and won people quick but when they grew too close sometimes they became confused, not certain who he was, so he was content to keep relations at school superficial and pleasant.

The students and steady gentle hush of rain gradually faded from his consciousness like a tide ebbing away and he drifted into one of his rare hypnotic reveries to another world, one he preferred not to remember, to early memories of Suspan Ontario, a thousand miles away into the remoteness of the northern boreal. They came as if by their own accord until he was far way from essays and red brick buildings. They came without the immediacy of feelings but they were somewhere, held in suspension just far enough away.

The clean shallow Mawgi creek came to his mind, a place of refuge, flowing beneath a glowing canopy of birches and tall poplars, over shimmering rocks in broken sunlight, and the wind carrying grandmother’s voice over a field of long grass and through stirring trees searching for him. She would call because it was meal time or getting dark or just wanted to make sure he was safe. She would continue to call until he came home, poised like an opera singer at the back of the dark gray unpainted house with curling red shingles where an old scarred tire lies with long grass in the middle. If the wind was strong and the trees really noisy she knew to call at a higher pitch, holding it longer and letting it drop just so, and it would carry better and find him like an ethereal bird gliding through the waving branches. Once he ignored her until she came over the field with long grass, erect, lifting her legs high, through the trees in her dress that looked like all her other dresses with a faded floral pattern and holding closed her worn sagging beige cardigan sweater. She found him and asked why he didn’t come. He told her he didn’t hear and got a sound licking. The next time she called there was a tingling on his behind when he heard her voice carried on the wind.

Things were never the same for Robert and his younger sister after they came to live with their grandmother. He was six and she was a year younger. On the first day it was the quiet strange tangible stillness in the air he noticed that was very different from his mother’s. And the smell was cleaner, slightly musty, but when he opened the plastic bag with all his possessions he could smell his home again -stale cigarettes, stale beer, unclean children, noisy nights, and his battered and dulled nerves reached out tentatively not knowing what to expect and their grandmother seemed distant at first. It was a long time before he could trust things were to be different forever.

Their grandmother, Anna Rebecca Polanski, was tall with a small low sitting round paunch, narrow shoulders and long gray hair kept in a ponytail or tight braided bun behind her head. She was sixty-three and looked ancient to him when still or rocking in her chair but when moving about her body was agile and fluid and could often catch his sister if she wanted and for a time frequently had to. It took a while for Anna to get rid his wild sister’s foul language and to stop scratching and making scabs on her forearms and legs, opening them over and over again and smearing blood. Anna would trim her nails and when it was really bad made her wear mitts and taped them firm around the wrist, making her sleep with them. Sometimes she bit off the tape and in the morning her sheets would be matted with dry blood.

He was deep into it, drifting from memory to memory and his sister’s boyish beautiful face with vivid angry green eyes came alive to him, and he remembered without emotion but they were there, always somewhere behind.

She had raged a terrific battle against Anna, standing her ground for a long time with the determination of a prize fighter. But Anna had an unfathomable strength and resolve resting on a code of morals that refused to yield. Emily’s rage withstood the spankings, isolation in her room and a call to chores was more often a call to battle. Then something occurred that seemed to come out of nowhere and she became calmer. She wasn’t broken or defeated but had gained an understanding. She was still the child with the wild green eyes that could flicker with rage and be defiant if she wanted but very suddenly she fell in love with Anna. It was a very poignant moment during one of their perfunctory battles, Emily bracing herself defiantly before her waiting for retribution but instead of the customary punishment Anna just bent down and took her into her arms. Emily struggled at first, then her tense body went limp and hung from Anna’s arms and Anna kissed the top of her head. And a gradual awareness emerged for them and she seemed to come to it first. An understanding of why they had rarely been brought to their grandmother’s and why their mother, who had seldom mentioned Anna, said only bad things when she did. And they knew there was another world other than the one they grew up in and Anna had become their guardian between the worlds. The world of rage and stifling darkness and Anna’s world. For a long time they were forbidden to take the mile journey on the black cinder path through the pines and an open field back to town without her. If they were to visit their mother Anna called ahead to make sure they were sober and always went with them. All this had come about because the school teacher finally seen enough and called the social worker in Edison.

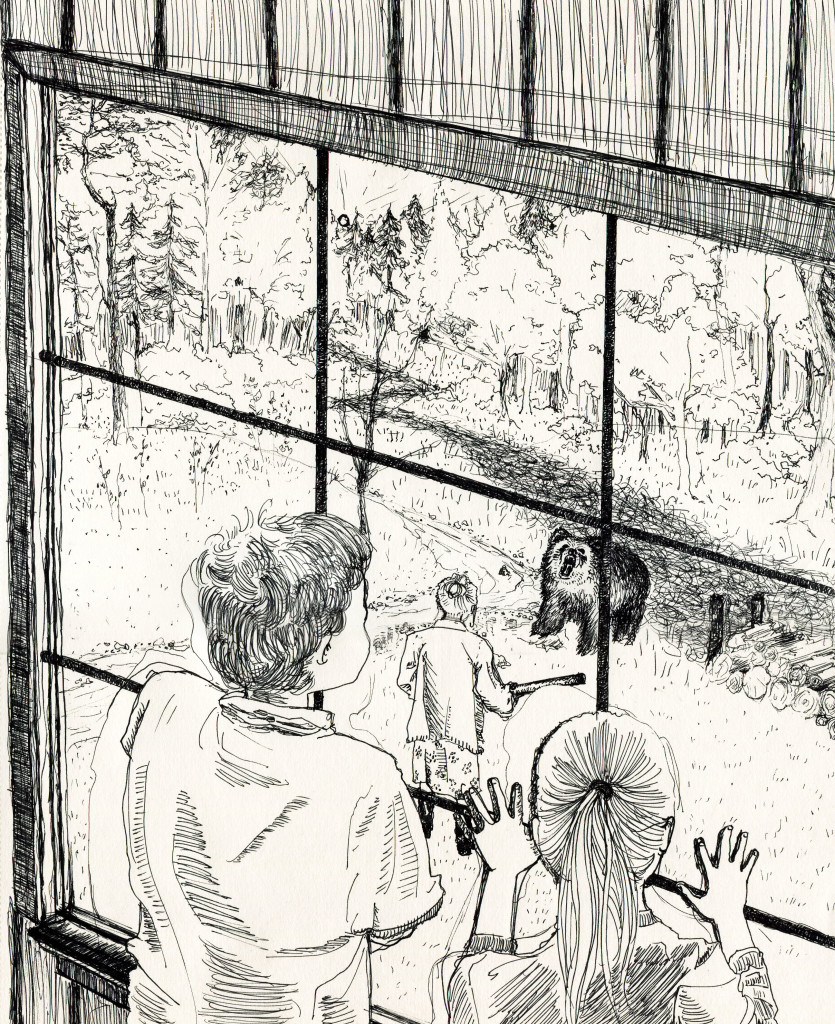

Robert was smiling faintly, unaware of his smile and that it was still raining, not hearing the noises of dorm life, remembering a cool early June when they had run swiftly into the house twice in three days telling Anna with wide eyes and frantic gesticulating they heard something big in trees and dense tall scrub at the end of the backyard. Each time she went out and listened attentively but always too late. There’s only four neighboring houses where they’d lived, a mile outside Suspan proper, and when the poplars were in full bloom the only one you could see from Anna’s was the corner of the Andersen’s porch. Throughout the week she’d sit outside on a crooked derelict wooden Adirondack chair watching them play and listening. Shortly after, very early as the stars were disappearing in the morning sky, he was awakened by dull thumping from Anna’s room across the narrow hall. Only curtains hung over the bedroom doorways and he heard clearly Anna rushing through her closet. When he pulled his curtain back to peek she was going down the creaky stairs sliding her hand along the rail with a shotgun under the other arm. He shook Emily from sleep in the bed across the room and they hurried down just as Anna was going outside. She turned and told them to stay inside and pulled the plaintive windowless wood door shut with a stern snap. They sprang to a window and watched her march by, holding the shotgun slightly bowed in her drooping cardigan and night gown, until she passed out of site. They bolted to the next window and she came and stood just before them. They strained with their heads against the glass trying to see what she was looking at but couldn’t see far enough around. Anna put the gun to her shoulder while they watched with fascination. The sun was still behind the trees and a delicate mist hovered a few inches from the short grass and around her green rubbers. The gun cracked twice pushing her shoulder back violently, startling them. She lowered the gun, observing for a moment then marched out of site and back into the house and they rushed to meet her.

“Don’t go touching it. It’s full of ticks,” she told them and they rushed outside.

After studying the huge black bear lying in the misty grass on its stomach with suspicion and awe Emily skipped around it and chanted,“Gramma shot a bear. Gramma shot a bear!”

“It’s full of ticks,” he whispered in his dorm room not realizing he did.

Even now he had no explanation for his mother’s bizarre rage and anguish. It was like she was sailing away on a journey into darkness, away from light and life, in self-imposed bondage to a ship on a doomed voyage. Men would last about a year with her, drawn to her fine figure but were expelled or fled for self-preservation. The one there at the time had been with her the longest because he was a hard empty man with little to sacrifice inside and even took some pleasure from her dark bent.

She came to see them after a month with her hair pulled back tight like Anna’s, strangely quiet, very sober, and Anna was quiet and accommodating. Their mother struggled to be normal but the circumstances were just too outrageous for her and she seemed on the verge of crying. Robert and Emily were guarded and observant, especially Emily. She was fascinated with her mother’s effort. She hugged them very tight before leaving, almost painfully tight.

A couple visits later she was calmer and almost two had months passed and they hadn’t witnessed her dark side and they began to accept her coming to see them. Then one night the dark stillness was violently ruptured with yelling and banging on the front door and through the old house their mother’s familiar drunken raging obscenities reached them and they sat up frightened. Anna’s light came on and she pulled their doorway curtain back and told them to stay in bed but they followed and sat high on the steps watching through the spindles. Anna unbolted and opened the door, went quickly into the porch closing the door behind her and they heard thumping flesh and things being knocked over and their mother screaming.

“You evil bitch, they’re mine. You have no right!…No right! I’m taking them!”

And more dark obscenities. They couldn’t hear their grandmother saying anything and the thumping stopped and the screaming continued to the side of the house. They pattered quickly down the steps to the kitchen window and could see their mother in the kitchen light that reached into the darkness, backing away quickly almost falling backwards and Anna marching forward like she had with the bear until they were out of sight and Emily started screaming, clenching her fists tight, crying and shaking with rage.

“I hate you! I hate you. I hate you…”

Robert went outside unable to see them in the dark but the obscenities continued, further and further away into the darkness along the cinder path through the pines until he couldn’t hear them anymore. He waited until he heard his grandmother’s steps crunching on the cinders then went back into the house. She came in almost breathless and looked at them briefly, went to her rocking chair and sat resting her head back with her eyes closed looking very tired and there was sweat on her forehead.

“I hate her gramma. I hate her!” Yelled Emily shaking and crying. Anna looked at her then put her arms out with her head still back and Emily went running into them embracing her tight and Anna rubbed her back while Emily cried into her chest.

“I tried…I..” said Anna still gaining her breath and looking for words. “I did my best..I could only do my best..The Lord knows..”

“I hate her gramma.”

“Don’t say that my girl…Your mothers not well…You must forgive her for gramma…”

Loud rapping on his dorm door startled him.

“Mueller!?”

Without getting a chance to answer, the door flung open and short, slightly feminine Eric Foster was posed mockingly in a manly ready for action way.

“Mueller. All work and no play will make you a Martha. A crazy monkish Martha. You’ll end up old and alone rubbing all kinds of creams on yourself, running back and forth to the doctor with imaginary illnesses. Get up man! Rise off that chair of toil! Night is coming and my goodest goodliest and kindest parents sent me precious coin and…”

Robert turned around in his computer chair and his friend was silenced.

Emotion had touched thought and his eyes glistened and he looked at Eric with anguish.

“I left them behind! I left her behind. I don’t know why I did!”

Eric was stunned and helpless seeing his friend in such a state.

“…who bud? Who you talking about Rob?”

“I left her behind. It’s because of her… She protected us…”

They drove most of the night in Eric’s just reliable enough hatchback until daylight revealed a low iron gray sky over a small northern city with tall smoking steel plant stacks reaching high into the grayness. Lori and April, who knew Robert from the time he came to the university, couldn’t be stopped from coming along after Eric told them Robert’s story. They had chatted happily during the ride and he’d been mostly quiet, grateful for their distraction. They waited, huddled in the cool dampness at the train station and the girls hugged him before he boarded.

“Remember, we’ll be here Saturday, and say ‘hi’ to your grams for me Rob,” said Eric and they waved as the train pulled away.

*****

Read More by Glen Louttit HERE.

About the author: Glen Louttit was relocated from Thorold, Ontario at the tender age of 6 years old when his mother moved their family back to her home town in Northern Ontario. He grew up in Oba, Ontario where the population during his life time never exceeded eighty-five. It was shocking and beautiful and after a short time Glen forgot that he ever lived in southern Ontario. Always a writer, over the last two years Glen has written a collection of short fiction, most of it set in the North. Says the author, “I think some of these stories came out of a longing to be there. At fifty seven years old, living and working in the Sault, I look forward to retirement so I can go back.”