A Rough and Ribald Story of a Lifetime in the Bush

~by Robert Cuerrier

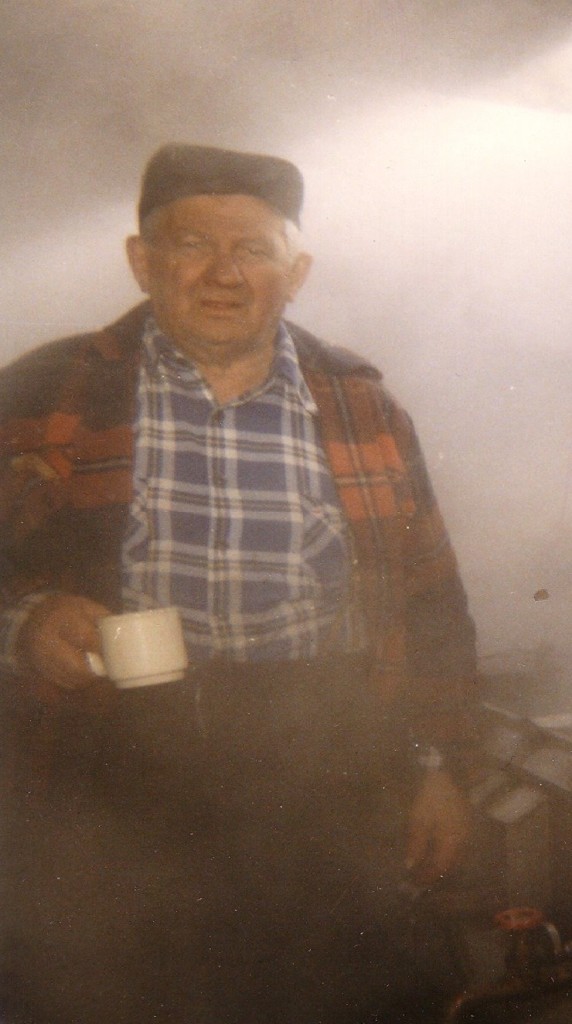

Chapter 2 Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

The old man was a rough-cut. After grade eight he went to the logging camps. He used to say, proudly, that he was illiterate in both official languages.

Firewood (Farwood)

Perhaps the most important wilderness skill is being able to make and maintain a campfire for cooking, warmth, and comfort. I have always prided myself with being able to do this with ease- scanning the bush with a glance to find dry deadfall for wood, locating sheets of birch bark for tinder. My gifts were only a small spark next the conflagrations that was the huge talent of Leonard St. Jean Baptiste.

On the moose hunt one sodden autumn we were damp coming onto mean- day after day of driving rain. We were ranging further and further to find dry wood and not very successfully. You couldn’t dry out around the fire at night; the rain was too persistent. We were hunting and didn’t want to stop and work on the dry out during the day. So we crawled into clammy bedding each night and it was getting colder. The strong drink had run out days before. There was no comfort.

Coming in and off the stand one night I could see a plume of heavy smoke behind the camp. The Old Man had found a towering standing dead white pine that was hollow at the bottom. He had loaded it up with large sheets of birch bark and put a match to it! The hollow acted like a draw, a chimney, and the fire raged like you could never expect in that weather. We stood well away from it. After a while the tree came down and shattered into thousands of bone-dry slabs, which we hauled back to camp for a fine dry out fire.

Leonard had always had a particular flare for pyrotechnics that went back to his days busting out new land on the farm, a job the pioneers did largely with matches.

An Old Boot

“If I’d a known I was going to have to make a life in the bush I’d have asked God for hooves.” ~ Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

First Aid

Old Leonard St. Jean Baptiste committed, for him, an unnatural act. He cut himself, and badly (with the bucksaw) between the thumb and forefinger. I looked at the wound and suggested we bail out. It was one hell of a deep and ugly gash. We were hunting, way down and off the Sand River, miles and many portages from the ACR track. There was a down train the next day but nothing until a week after that. I figured that if we hurried, we’d make that train.

The Old Man said that wouldn’t do and called for the first aid kit. Well, we rooted through the packs and couldn’t find it, so he took up the search all the while calling down his dumb-assed sons. When he brought it to hand, it turns out to be a small bottle wrapped in a rag. It was Holy Water from the Church and right out of the font where the entire parish had dipped their fingers. Hell and perdition! So he anointed his wound with this, all the while invoking the Spirit of the Blessed Virgin and pledging a Novena. He wrapped the near amputation with his rag.

I let it all go and didn’t’ say damned thing until a few days later when curiosity got the best of me. He could have had gangrene setting in, and yet he’d never blink and say so. I asked to have a look; see, I was camp cook, and doctoring was a part of that role, so he had to acquiesce. There wasn’t a hint of putrification. It was knitting together perfectly. Amen.

Child Rearing

You always knew the Old Man was out of patience when he spoke to you like he did the dogs. “Git and lay down!” ~ Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

Tabor Line Camp

Something seemed to come over the Old Man when he hit the bush. I came to understand through time that it wasn’t a complete metamorphoses but rather more of him just being himself in a way that just wasn’t as apparent in town.

Something seemed to come over the Old Man when he hit the bush. I came to understand through time that it wasn’t a complete metamorphoses but rather more of him just being himself in a way that just wasn’t as apparent in town.

First thing he’d do on arrival at his old trapper’s shack that he adopted as a squatter was to root in the trunk for a change of clothes- tattered vintage rags left over from his predecessor, stuff that had never been washed or patched in the last forty years. Changed everything but his underwear. It was just his nature to use everything up.

He also felt compelled to hike the whole trapline even though we could have caught all the fish we needed and hunted big and small game right from the main camp, successfully and with little or no effort. Leonard had to walk the line- just because he felt it was the thing to do.

This need brought us time to time to the Tabor line camp about three or four miles way up on the Tabor Creek. The first time we were there I was still a kid and my younger brothers toddlers. It was mid-November, the snow too light for snowshoes, too deep to walk through without effort. Leonard thought nuthin’of it.

The shack was about seven feet square and had a box stove way too big for it. The old man lit a fire and after a closer look around assembled us outside to show us the flames and sparks leaping out the short length of pipe on the rooftop outside the shack; we’d have to carefully bank the stove before sleeping in there.

We got moved in, and Leonard lit a candle, pushed away the cobwebs, and commented on how well-appointed the place was. Our dinner was light, since we didn’t have any luck with small game on the way in and didn’t have any time to fish or set snares before dark. The old man looked over the shelves and brought down a can of strawberries that I judged to have been better than twenty years old: opened it with his knife, stuck a finger in and licked it as a test before proclaiming it safe and offering it around. I shook my head negatively to the kids without him seeing, and they understood. We watched Leonard enjoying his dessert. He had the stomach of a wolf and felt no ill effects.

We readied for bed. Leonard settled commodiously into the single bunk. The rest of us were left to circle and sniff like dogs deciding on a place to lie down. The kids slept with their legs crisscrossed over one another, one with his head under a bunk. I opened the door a bit and threw a rain poncho over my legs that stretched out into the weather. You know none of this seemed unusual at the time, but my brothers and I sure get a kick out of the memory today.

Counterfeit Philosophies

Leonard was old school and might even be called a regressive conservative. He found nothing more disturbing than the emergence of the recent eco bush cult that he considered goofy- the belief that the wilderness can only be experienced if there’s a certain degree of risk-taking. EXTREME! You swim an ice-choked river, stay up for days, and tempt the fates at every turn. Maybe die. Have friends rationalize at the funeral “He died doing what he loved”. “This is nuts,” he thought.

This is such a contrast to the traditional bushmen, all of whom practiced cautious, deliberate thought and action. They often lived alone and harboured no testosterone-driven romantic illusions. Using an axe, traveling over varied terrain on foot and by canoe in all kinds of weather…well that can be risky enough.

Every time they put a foot down they knew where it was going. They didn’t have to look for trouble, for it sometimes came calling without invitation.

Leonard St. Jean Baptiste Cuerrier voiced his credo with a litany of cautious admonishments that he toted out every time you left the shack. “It’ll be all hardship and misery!” or “Mon Dieu, don’t even try that, you’ll perish!” And his favorite, delivered with just a hint of hysteria in his voice “Don’t take no chances boys!” Yet he enjoyed the difficulties dangers and the snarls- ever a Roman Catholic and a fine penitent. He even liked plenty of knots in the firewood he split.

Traditional Paddling Tune – Sung often by Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

“Au pres de ma blonde…

Qu’il fait bon, fait bon, fait bon

Au pres de ma blonde, qu’il fait bon dormir”

Social Grace

Leonard liked his solitude. When he was in the bush he didn’t care to have it broken. Occasionally someone might drop by, and when they got back into their canoe he’d whisper his goodbye as an aside to me “Come again when you can’t stay as long”. He often liked to work alone too. One day he was making firewood, a big log across the sawbuck and using a two-man crosscut saw by himself. I saw this and came over to help him, when I noticed he’d placed a work glove on the handle of the other side of the saw. I asked him what that was about. I knew he was in one of those moods and left him alone when he spit out a wad of tobacco juice and said, “That glove is as good as any man I’ve ever had over there.”

Waiting For The End To Come Along

In the end old Leonard sat in his chair given to vaporous reminisces and thousand yard stares. You could see that he was drifting back to when he was young and strong.

Leonard St. Jean Baptiste, This Was His Eulogy

Dad passed away a few days ago, Leonard St. Jean Baptiste Cuerrier. A proud member of the Métis Nation- his spirit now cradled in the arms of the Blessed Virgin.

Dad was tough and stubborn. I can remember long ago in 1951. It was a very rainy windswept November and he’d been ploughing with the horses every day. His shoulders swelled up double their normal size. The doctor paid a couple of visits (they did that then) and finally said to him, “Look Leonard, you’re going to have to buy a raincoat.” The old man looked back at him and said “Raincoats are for city people.” And that was how things were for him.

He had a strong faith. He was an old-time Quebecois Roman Catholic. The chief tenets of his religion were obedience, suffering, and hard work. “The farmer obeys the curé, the curé has his ear to the bishop, the bishop follows the Pope, and the Pope is spoken to by God.” He lived it.

Holy water from the Church had special powers for him. He dressed all his wounds with generous doses. He was thrifty- used to go to the basement and pull his own teeth before he’d pay a dentist. All his faith healings were abetted by liberal doses of strong drink.

Leonard was the product of a different era. He was hardened and sometimes brutalized by very hard labor in the bush, the farm and his trapline. We had no running water at home. He filled an icehouse with blocks cut from the creek. That was our fridge. He made firewood for the house and cleared new land for farming.

His view of women was old time and kind of funny. Women were cooks, child rearers and caterers. Leonard had the low mind of a lonesome lumberjack in his assessment of their beauty. He liked big, husky, robust gals. “Two axe handles an’a plug o’chewing tobacco wide across the beam” made a handsome woman, he said.

In the end he was just waiting on the Judgment Day. Old as he was, there’s not much sorrow in his death. As a family we celebrate his life for the good that was in it and for what inspiration we can draw for fulfillment in our own.

*****

Robert Currier, or as many know him- Farmer Bob, has lived on the land traditionally most of his life. He has built wilderness log cabins, logged, guided and prospected. He was the first recipient of the CBC/Big Brothers “Northern Moose Award” for best personifying the spirit of Northern Ontario.

Robert Currier, or as many know him- Farmer Bob, has lived on the land traditionally most of his life. He has built wilderness log cabins, logged, guided and prospected. He was the first recipient of the CBC/Big Brothers “Northern Moose Award” for best personifying the spirit of Northern Ontario.

Farmer Bob lives on his Mockingbird Hill Homestead Farm in beautiful Hiawatha Highlands, which backs onto Odena, Mile 9 on the Algoma Central Line. The farm is a singular burst of colour and beauty and one of Sault Ste. Marie’s premier attractions. It is open to the public year round.

Mockingbird Hill is a horse drawn replica of a Métis homestead in the thirties and forties. In summer the farm features wagon rides, market gardening, a petting barn, a corn maze, and a spectacular wild flower walk.

In winter Mockingbird Hill offers horse drawn sleigh rides and cutter rides on trails that are breathtakingly beautiful by day and romantically lantern-lit by night.

De Big-Shot Train by Robert Currier can be purchased at the Art Gallery of Algoma.

1.705.253.4712