DE BIG-SHOT TRAIN: A Northern Love Affair with Algoma Central Country

A Rough and Ribald Story of a Lifetime in the Bush ~ Robert Cuerrier

Chapter 8 Living Camp Life

MOVING ON

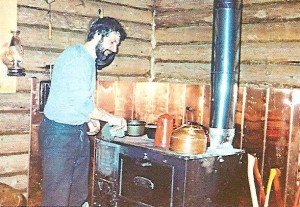

As soon as the roof was on a cabin I moved in, hesitantly, like a dog being allowed in the house for the first time. By this time it would be late summer and the rains started, so it was good to get out of a damp tent. The first few days I slept just out of cremation range of the woodstove, absorbing as much of that dry heat as possible.

The simplicity of the outdoor kitchen was still appealing though, and since I still had to build the interior, I didn’t want to get in my own way indoors. So I cooked outside.

I had a tree beside the fire that was my cupboard. On it hung the fry pan, a pot, my mug, a pair of gloves for oven mittens, a wrecking pan to do dishes in and a tin can that housed a knife and fork. There was a pail to fetch water from the lake, which was just a few steps away. The fire burnt up disposals, and there were no floors to sweep, no counter to wipe. I found it easier to cook outdoors until the snows came and the inside construction finished.

After I’d moved in full-time it came to me that living in a log cabin has none of the affected artificiality of the modern home. In many ways you’re living within the same natural rhythms that feel so good when you’re camping outside.

You can still feel the pulse of the earth and your connection to it. Rains beat on the roof and you hear it. You can feel the snows and blows, winds seep through crevices in the walls and doorways, sunlight shines through uncurtained windows, and then at night as the woodstove slows the temperature drops like it would outside. In summer a few maverick mosquitoes wake you up towards dawn. During those times in the night, when you come to semi-consciousness, you get a good feel for the weather outside.

Your body dovetails to the cycle of life. The evenings are lit with a candle and a kerosene lamp. There’s nothing more romantic than reading by lamplight just before bed. You learn to use the daylight, to go to bed early and be up before the dawn, to work longer days in summer and rest a little more in winter. I kept an ice hope open and toted water up in pails. Real, fresh and pure water, likely the cleanest on the planet.

Even in the coldest weather I’d let the woodstove burn out rather than feed it throughout the night. The eggs would be wrapped up and placed at my feet so not to freeze. There was a heap of coverings beside my bunk, and I added them as required as the night cooled Sometimes the weight of them could become oppressive.

In the mornings I’d skip across the cold floor and quickly toss birch bark, kindling, a few small sticks, and a match into the stove then take to my blankets again. After a few minutes with the fire burning strong I’d ;load the store right up and go back to sleep then wake up later in a warm camp. I always felt so wonderfully indolent.

It snows heavy up north so the camp roof would have to be cleared a few times. Soon the snow would reach the eaves, and holes would have to be cut out for the windows and doors. The snow made a fine windbreak and insulation, so it became easy to heat the cabin. Now I know that snow has been used throughout time as an insulator, but who ever thought of completely burying the camp. I thought that I’d made a breakthrough discovery and was sovereign in this belief until recently.

I saw a documentary about Hudson’s Bay posts up north in the twenties. They’d hire the Inuit to fortify their frame buildings against the weather with exterior snow block walls. And of course today they even have the ice hotels at major winter carnivals in Quebec City and in Europe.

You knew it was mid-winter when you’d wake up in the mornings to the sounds of the dogs running around on the roof, letting you know that it was time for breakfast.

OF MICE AND MEN

You take any bush camp and you know it’s got mice. Filthy little vermin. You take steps. All foodstuffs go into large airtight cans, onto open shelving that is easy to clean Pots and pans are hung up. An airtight trunk stores the bedding and other stuff they will assault. Minimize your outfit so there is less to deal with.

Of course there are all sorts of controls. Everybody’s got a better mousetrap. Two fellows I knew, who were hovelled up in an old, cramped, and decrepit log shack while on a prospecting chance, took extreme measures. It amused them to shoot the mice with twenty-two’s and they kept score in a competition. The whole camp and contents were scarred, chipped, and perforated. You were slow in your movements and nervous when you visited.

For a while, one winter I had a weasel living in the woodpile inside the shack, which I thought was as good as having a house cat. I never spooked him and, like any relationship you’re working on, I granted him a high degree of tolerance. But we didn’t make it.

The weasel all the time startled me- darting here and there, always in my peripheral vision with a sudden movement. It especially bothered me when reading or relaxing. I ended it, ran him off, and went back to tending the mouse trapline.

SPOOKED

I was frightened and confounded – the hairs on my arms and the back of my neck were dancing. I’d come to camp alone after a long absence to make wood for the coming winter. No moon, black and overcast, you could hardly see your own thoughts without a light. I was awakened in the night by something metallic- sounding locomoting across the shack floor, bumping into one things and then another, never stopping –a real catamount!

For a long while I tried to puzzle it out as I lay there but had no theories. So I figured, hell, I might just as well light a candle and greet the aliens. But they weren’t so foreign. It was the minnow trap. I had baited it with some bread working ahead, planning on throwing it out in the morning. It was filled with mice, and they had run it like a treadmill: some were dead and cannibalized, others had run their little feet off to stumps. I threw it in the lake and went back to bed.

OUTHO– — — USES

Even today, the outhouse serves Algoma Central country: the privy, crapper, sugar shack, backhouse, shitter, or closet. And many of us who live or have lived there like them. It’s peaceful sitting there in solitude, watching nature with the door open. There is the silent tranquility of the no-flush and the immunity of being able to pee anywhere without fear of the neighbors bearing witness. My friend, Big Track, who has always lived in the old ways looks with beguiled amusement at the white folks with a toilet room in the same house where the cook, sleep and live.

I liked to make my privy kind of homey. There was a bin of hardwood ashes and after each use you’d sprinkle a scoop down the hole to eliminate odors. The walls were wallpapered with major news stories from the newspapers – at the time, the moon landing, Vietnam, Watergate, Nixon, the Beatles, and Hippies –something for everyone. And of course, in a salute to days gone by, the Sears catalogue was in the outhouse.

The catalogue was, in its day, an institution and so much more than toilet paper. It was the stuff of fantasy, of musing over things you needed, what you’d like to be able to buy, a link to a larger and seemingly more cultivated world. And to many generations living before family life programs were taught in schools, sex education was learned in the outhouse. The boys perused the women’s lingerie, the girls the men’s underwear. Didn’t matter that the women’s section was largely industrial foundation garments and the men’s heavy woolen longjohns. It was oh so erotic.

When I was a kid, only when company came would my folks put out real toilet paper. We often bought baskets of pears and peaches that we didn’t grow ourselves, and my older sister and I would flatten the soft fuzzy-papered fruit wrappers each piece came in and place them in the outhouse. That was nice for a while.

Old Leonard told me that when he was young the catalogue changed from rough to shiny paper causing one hell of an uprising among rural folks.

The camp woodpile is always practically located somewhere between the camp and the outhouse. Custom has it that on the way back the men take an armload of firewood for the wood box. Women bring back a basket of chips for kindling, and for the demure it kind of belies where they’ve been.

There were also thunder mugs and pee bottles under the bed for use on cold nights, but some memories are best repressed.

CONTEUERS DES CONTES

After a time in camp, a good storyteller becomes just as appreciated as a good cook. My buddy, Giroux, was the best. He could really lift your spirits and make you laugh. Around a campfire at night his stories were coming randomly, kind of like the way a horse drops manure.

Giroux was a throwback to the days before logging and exploration camps had TV or radio. Every camp then had a storyteller: some men were hired on just because they had this skill. After supper a hush would fall over the camp, and the men would gather as children for tis diversion. Some stories were short and could be told at a single sitting, many were serials and even epics that might take the entire season to tell. Men would change camps time to time to hear an unfamiliar or renowned storyteller.

Perhaps Canada’s most famous storyteller was Klondike Mike Mahoney. Mahoney had been a colorful musher during the Yukon Gold Rush, a man who had made and lost several fortunes. His most telling exploit had been taking out the body of a deceased judge through unmapped wilderness, a trip so perilous it weakened him to the point where he carried on delirious conversations with the corpse.

Anyway he became a multimillionaire who then enjoyed working the guest-speaker circuit as an amusement right up until his death in the sixties. He said he learned early that people were often disappointed with the unvarnished truth, so he began pumping up his stories.

He was regularly telling a whopper about witnessing the shooting of Dangerous Dan Mangrew, a character in the famous Robert Service poem.

Some young reporter thought it would be clever to expose him as a fraud and waited to do so until a well-publicized anniversary gathering of pioneers and aficionados of The Rush. He nailed old Mike, interrupting his story with a challenge. The old man stood speechless, vulnerable, crushed, exposed and alone.

The silence was only broken when, on after another, the old sourdoughs stood up to testify in defense of Mahoney, saying they saw it too or knew of someone who did.

Sometimes, so as to honor the tradition and to keep it going, you’ve got to let a man lie like hell, and you swear by it.

BOOKS

The pages of every book I’ve ever read up north are smudged, are encrusted with candle wax drippings and smell of woodsmoke. The near blank pages at the beginning and end of the books are full of my journal entries. There are few pleasures in life like reading by the woodstove and under candle light on a blustery winter night when you are alone in the bush.

I’ve read thousands of dusters, since they are a common currency passed from hand to hand up north. I’m sure I could put forth a doctoral thesis on the writings of Louis Lamour. His stuff blended into reading all of the Time-Life series on the West and on the Indians. I read volumes on the settlement of the Canadian West, on homesteading, on the fur trade. Lots of oral histories. Liked the stories about guys on the run in the wilderness – Albert Johnson, the mad trapper, and Simon Gun-nannot.

My favourite are those that are deeply expressive of the north and northwest: Pierre Berton’s Klondike, easily the best piece of Canadiana ever written, Maggie Siggin’s Riel and Peter Newman’s trilogy on the fur trade.

THE LAST CAMP

By the summer of ’74, I was sitting on the verandah of a camp I was building, feeling dissatisfied. Pissed off with flies, not enough money, no bright prospects, brooding, working alone, the lack of company of women, being dirty, boredom, hard labor, bad weather, the outhouse, yappy dog, with slivers, cuts, scrapes, being seventy miles form a Honky Tonk, and with the out-loud, angry, repetitive conversations I was having with myself. To paraphrase a guy, I’d seen the future and it was much like the present only longer. I was bushed, and the decision was made. I’d go downtown to the Soo and charge right into the most cosmopolitan lifestyle I could find.

WISDOM

“There’s no sense paintin’ up an old shovel.” ~ Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

DOWNTOWN

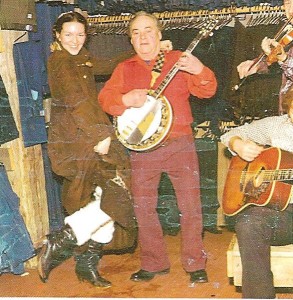

I opened and owned two smokin’ wilderness-themed clothing stores: Ogidaki Mountain, one of the most successful jean joints in the country, and Wildflowers, a contempra ladies wear store. I was scripting and arranging dance steps for fashion shows. And cool too, a media darling and the last word on hip. Just a few months before everything I wore came from the re-claim store. I was an entrepreneur, was said to have a genius for thematics and marketing, and the money was flowing in faster than I could have spent it on Saturday night. I was a ladies wear buyer with a propensity for lingerie, traveling and working in the big towns –Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa. Big Times. Eight years later I was broke and back up the ACR.

RIDING THE TRAIN DURING THE BIG TIMES

Of course I was bending like grass in the wind during the Big Times and often needed the bush as a reference, to get standing tall again. And so I’d go back in time to time. Brought in my homework too: Style, Vogue and other trade papers to read on the train. I’d tear the covers off lest one of the boys sitting down with me saw what they were.

COMPLEXITY

When your life and maybe your emotions were running over some rough country, the old man would bring it all down to basics for you. “Life is simple dammit. All you gotta do is breathe in more than you breathe out.” Spoken by Leonard St. Jean Baptiste.

*****

Robert Currier, or as many know him- Farmer Bob, has lived on the land traditionally most of his life. He has built wilderness log cabins, logged, guided and prospected. He was the first recipient of the CBC/Big Brothers “Northern Moose Award” for best personifying the spirit of Northern Ontario.

Robert Currier, or as many know him- Farmer Bob, has lived on the land traditionally most of his life. He has built wilderness log cabins, logged, guided and prospected. He was the first recipient of the CBC/Big Brothers “Northern Moose Award” for best personifying the spirit of Northern Ontario.

Farmer Bob lives on his Mockingbird Hill Homestead Farm in beautiful Hiawatha Highlands, which backs onto Odena, Mile 9 on the Algoma Central Line. The farm is a singular burst of colour and beauty and one of Sault Ste. Marie’s premier attractions. It is open to the public year round.

Mockingbird Hill is a horse drawn replica of a Métis homestead in the thirties and forties. In summer the farm features wagon rides, market gardening, a petting barn, a corn maze, and a spectacular wild flower walk.

In winter Mockingbird Hill offers horse drawn sleigh rides and cutter rides on trails that are breathtakingly beautiful by day and romantically lantern-lit by night.

De Big-Shot Train by Robert Currier can be purchased at the Art Gallery of Algoma.

1.705.253.4712