For Derrek Coccimiglio, Red Bull really does give him wings. Catching air and zipping around tight corners on a polished iced surface at speeds ranging from 45 – 70 kilometres an hour, has become the norm for the Sault Ste. Marie native. Ranked 50th in the world overall, Coccimiglio has become one of the hottest contenders in the death-defying Red Bull Crashed Ice competition, which is taking the world by storm as one of the newest extreme sport crazes.

The Red Bull Crashed Ice, or ice cross downhill as the sport is commonly known, involves four people, dressed as ice hockey players, racing on a sheet of ice in an urban setting. Unlike other ice skating events, ice cross downhill occurs on a specially designed race track, outfitted with jumps, moguls, tight turns, inclines, and declines. The track ranges from 250 metres to just under 500 metres in length, and comes equipped with its own cooling system to ensure the ideal racing surface. “It takes a little bit to get used to at first,” says Coccimiglio, who just returned home from Quebec City after racing at one of the stops for the Red Bull Crashed Ice world tour. “You’re sending your head for a loop, more or less.”

Yet, for Coccimiglio, who has been on hockey skates since the age of three, ice cross downhill came easily to him. So easily, in fact, that he came in 4th place out of 250 other skaters in his first ice cross downhill competition tryout.

Coccimiglio first became interested in ice cross downhill after seeing a commercial on television advertising the phenomenon in 2011. “It was between me graduating from college and finding a job that I saw this commercial for Red Bull and before it was over, I was hooked. I was fired up.” Despite having played hockey since childhood and having made Junior B hockey teams in both Listowel and Sarnia, Ontario, Coccimiglio knew he would never have a future in professional hockey. “Skating was always my strong point in hockey. I always hit the post so it didn’t progress me to the next level,” he adds with a laugh.

After doing some research to better understand the sport and the playing structure, and further developing his strengths on skates, Coccimiglio applied to race in one of the preliminary tryouts in Windsor, Ontario. Finishing 4th enabled him to qualify for one of the main events on the Red Bull Crashed Ice world tour. He competed on the world stage for the first time in Quebec City, finishing 83rd overall with 5.6 points.

Now in his sixth season, Coccimiglio has had 15 Red Bull Crashed Ice performances (including in Minnesota, Quebec, Alberta, and Northern Ireland) and countless Rider Cup finishes. His last race in Quebec City was his best to date, finishing 23rd overall, bumping him up from being ranked 65th overall to 50th in the world. He finished the race with 80 points and was the 7th Canadian to cross the finish line. In the New Year, he plans to travel to France and Finland to compete in two Rider Cups, hoping to podium, and further improve upon his world ranking at the main Red Bull Crashed Ice event in Finland.

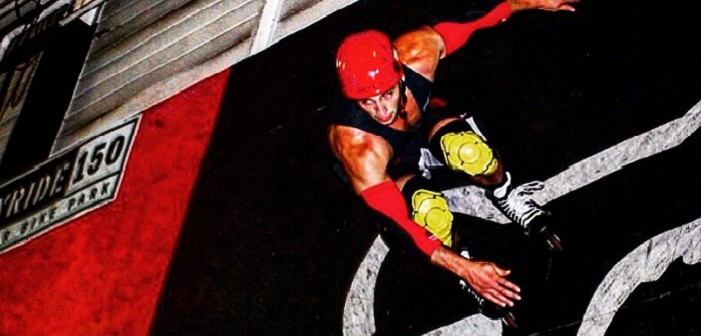

Despite finding his footing in the sport early on, success hasn’t been easy and takes great dedication and motivation. Coccimiglio trains daily, whether in the gym, or conducting exercises at race tracks, outdoor rinks, or at a special pump track in Markham, Ontario. “For me, I do a lot of inline skating. I train in Markham at a place called Joy Ride 150, which is designed for BMX and mountain bike riders, but they’ve been great allowing most of the Ontario racers to train there. I also use the city oval a lot and do parachute training and laps. The more outdoor rinks I’m on, the better because the ice isn’t perfect. And the ice is far from perfect when we’re racing.” Coccimiglio also competes in the summer months in fire fit competitions and in the St. Joseph Island Duathlon to stay in top physical shape. He bikes, has switched from snowboarding to downhill skiing to perfect his stance and speed, and works hard to maintain his weight, tipping the scale at 200 pounds. He is hopeful that the City of Sault Ste. Marie will install its proposed pump track sooner than later to prevent him from having to travel to Southern Ontario to receive training on similar conditions to those he races on. “We all train a lot. The training has really stepped up in the past few years as we’re working on making ice cross a professional sport.”

Former World Champions and top competitors from Austria have designed two wooden plank tracks that mimic an ice cross downhill track to practice year round, taking the competition to a whole new level. Federations have also started to form in the ice cross downhill sphere in hopes that one day, they can reach the pinnacle of sport as Olympic Champions. “There’s a new movement in the sport right now to create a bunch of federations. So All-Terrain Skate Cross (ATSX) is our governing body. There are a few other ones in other countries right now, too. ATSX was founded this year. There are plenty of talks about making this an Olympic sport – though I’ll probably be too old by then to be competing.”

And because of this new federation, the overall competition has changed. “This year is a whole new year in the sport. There’s a different way to qualify for the events.” This new qualifying structure has worked in Coccimiglio’s benefit, despite his original thoughts that it would hinder any possibility of advancement. “I wasn’t planning on racing this year. With the new changes, it wasn’t going to work out in my favour. Tuesday night before the race [in Quebec], I got a call from the Sporting Director asking me if I wanted to race. I was actually at work for my last night shift, and I said ‘yes’. So I packed up the truck the next day and drove down to Quebec and was there 12 hours later, ready to practice on the track on Thursday. Things work in mysterious ways. I jumped from being 65th in the world to 50th. I moved quite a few spots and will hopefully keep moving forward.”

The new racing structure follows the same model of four people competing per heat. Athletes have to complete two time trials, and the fastest 64 competitors qualify to race. Before, there were national and international groupings. The top 32 national athletes would race the 33rd – 63rd top international athletes in a one-round knockout. The top two would move on to pair up with the top 32 international racers. They would then race and dwindle the numbers down from 64.

“So now, it’s just one main group who goes to the race. We play down from 64, and from 64 to 32, to the quarterfinals, to the semi-finals of eight competitors, then down to the final four.”

With the new structure in place, athletes get more practice time on the ice and the chance of injury has also decreased. Competitors go on exploration runs on the Thursday prior to racing, where they navigate the track and figure out which path is the best to take. On Friday morning, each receives two more practice runs on the track followed by their two qualifying time trials. A team competition headlines Friday night, and Saturday, is the main race after a two-hour open track for further practicing and warm ups. “By the time we’re racing on Saturday, we know that track perfectly. And because there’s a lot less people racing on the track all together because of the new structure, the ice is in better condition. There are less ruts to worry about. Though, there are always ruts that will send you on your face.”

For the 5’11” St. Basil Secondary School graduate, he has been lucky to avoid any kind of serious injury in the sport. “I’ve come away with lots of bumps and bruises but nothing too serious,” he says, showing off two major scraps and burns on his forearms from making impact on the ice two weeks past in Quebec City. “I’ve seen lots of dislocated shoulders in the sports and lots of athletes in slings, but for the most part, it’s a pretty safe sport. If you skate within your limit, you’ll be fine. But obviously, you always want to be pushing your limit to win.”

Plus, protective gear helps offset the damage and impact to the body. Every time he hits the ice, Coccimiglio is sporting low profile elbow pads, as well as specially engineered padding for his torso, designed by his previous sponsor G Form. He wears his motorcycle gloves to better protect his palms and a G Form girdle underneath his regular hockey girdle. Coccimiglio wears a hockey helmet, which has been doctored to include a lighter lacrosse mask for the cage. His eyes are protected with regular alpine goggles. He skates on Bauers, though they’re not your typical blades. He uses Step Steel blades, which are made with the highest grade of Swedish stainless steel. “They have more depth and a box cut. There’s more blade touching the ice, which allows for more gliding, but they still have an arc at the front for jumps.”

G Form has been one of many of Coccimiglio’s sponsors over the years. Last year, he was sponsored by Sony Action Cam, and in other years, by local companies. Although finding sponsors can be difficult for a sport that is still relatively new, Coccimiglio has been luckily. Red Bull has been generous with helping cover costs, including hotel accommodations and food while competing.

Yet, despite its relative newness, the sport is growing. Thousands compete annually in ice cross downhill and between 100 000 – 120 000 fans frequent each Red Bull Crashed Ice venue. Sportsnet’s dedication has also helped grow the fan base in warmer climates. “They’ve talked about bringing the event to warmer areas in America because more people are tuning in. But, I’m not sure how well that will work. I don’t know if the ice will hold up. It’s only designed for up to 10 degrees Celsius.”

Plus, the gender ratio is becoming more balanced with more women taking to the track. The 2015-16 year marks the first season that there will be a World Championship for the women’s division.

When not competing on the ice, Coccimiglio is fighting fires in the City of Sault Ste. Marie. He has been a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Fire Department for three years, a position he earned after graduating from Lambton College’s Pre-Service Firefighting and Fire Science programs. “The fire department is really supportive of me. Especially because I only take holidays in the winter – they’re all summer holiday people,” he says, laughing.

While many still cannot even begin to grapple the sport and the overt danger associated with ice cross downhill, Coccimiglio says that the community at large has been extremely supportive, including his family. His mom can often be found in front of the television cheering on her son when he is away at competitions.

Although he is an older competitor at 27 years, Coccimiglio doesn’t foresee retirement in sight. “Although I went into the year thinking I wouldn’t compete, I’ve learned so much from this past race that I can’t walk away now. I’m not retiring. I’m going to keep working at it. When my body tells me enough, that will be when I retire.” To ensure he gets the best performance on the track, he is currently working on his mental toughness, envisioning success and working to channel his adrenal and new fame. “It’s hard going from being nobody at these races to somebody in front of 100 000 screaming fans. It’s a really awesome and weird experience at the same time. The crowds will send you for an adrenal ride. I’ve worked really hard to be able to hold onto that adrenal and leave it all on the ice during the race. It made a big difference in Quebec, and I know it will keep making a difference. I’m really proud of my results in Quebec. And because of that, I’m not quitting just yet.”