The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has fulfilled their five year mandate to inform all Canadians about what happened in the Indian Residential School System. The testimonies from over 6,750 residential school survivors have been documented and have become a part of Canada’s historical record in perpetuity. In its report, the Commission issued 94 calls to action to the Government of Canada.

A component of the TRC has focused upon preserving the legacy of its work by establishing mechanisms that allow history to be passed on throughout the generations. These constructs are meant to keep the spirit of reconciliation alive. The Commission identifies two elements contrived over the five year process that are intended to keep the torch of reconciliation moving onward.

- Hosted at the University of Manitoba, the National Research Centre will “house the statements, documents and all other materials the Commission has gathered during its five-year mandate.” The NRC is also identified as a cornerstone network that will mobilize various agencies, institutions and individuals to pursue the 94 calls to action.

- Honourary Witnesses, or history keepers, have been identified and have the important task of bringing what they have learned to share with their own people.

So now what?

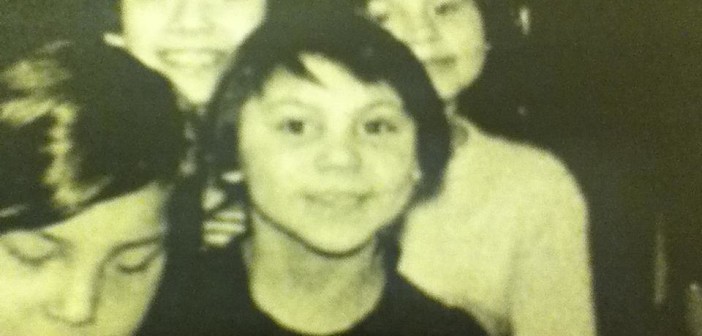

It is a question that many have asked including Garden River resident and residential school survivor, Barbara Nolan. Barb and her two sisters were sent to St. Joseph’s School for native girls and her two brothers were placed just across the road in Garnier School for native boys in Spanish River, Ontario.

“If the TRC is dismantled because they have reached their mandate to come up with this thing, who will hold the government responsible?” She said jabbing a finger at the 388 page executive summary of the final report. “Our political leadership?”

The final report is just over 800 pages. Barb notes that the account has value in providing a written testimony of residential school survivors but is dubious that the onerous document won’t become just another paper weight.

“I have a feeling that this will be a thing to talk about. But people aren’t going to understand this. Who’s going to read this big fat document? Us common survivors probably won’t,” remarked Barb. “What every community needs is to have someone organized through the TRC to come in and run workshops about this report so that we can all know what’s in here- and know what it means.”

It is Barb’s opinion that the TRC’s longevity should be extended to cover the implementation of the 94 calls to action. There is an expectation that the government of Canada will accept the document as a serious report. However, historically the government has exerted resistance in advancing First Nation concerns. In fact the current government inherited the TRC process from the prior Liberal administration. Even the apology from Stephen Harper was issued only because a judge ordered it.

“That apology meant nothing to me,” said Barb. “The apology from the Pope meant more to me. It meant more that the Church apologized to us. But the politicians’ apology- it didn’t mean anything.”

Barb and her siblings were kept in the residential school systems for four years. She was five years old when she and her eldest sister were dropped off at St. Joseph’s school. Her little sister would join them a year later. The little girls spent four years at the residential school but Barb benchmarks her time in the system next to the students who were held there for their entire ‘education’- 12 years.

“They never left. We went home at Christmas and in the summer. But they never did. They were just babies when they went there. They left not knowing who they were, not knowing their family, not knowing their community.”

Barb is grateful that she never lost her language but she bears the emotional and physical scars from her time at the residential school. Perhaps more difficult than the strappings she received on a regular basis for speaking her language was witnessing the abuse of other survivors.

In 1985, Barb had a breakthrough in her own recovery process. She was attending a workshop about grief in her role as a counsellor for students attending Sault College. That day she expected to acquire new tools that would assist her work with college students but instead was confronted with an unanticipated reckoning of her past.

“There was a medicine man running the group. We were in a circle- like a healing circle,” she recalled. “A woman in the group was sharing her experiences about being in the residential schools and my heart went right to her. There was a flash of my entire four years at the school through my mind. And I cried and I cried and I cried. I cried for my loss. My loss of dignity, innocence and childhood.”

Barb turned to her culture for healing and spoke about her experiences with other survivors. “I think the last part of healing is forgiveness. I think I am almost there. But I will never forget. I still have the painful memories but I have gone beyond that. And I’m willing to help other people.”

Before TRC’s inception was the Aboriginal Healing Foundation. Barb was hired by AHF to contribute to the development of a healing and wellness plan for communities dealing with the repercussions of systemic abuse wrought by residential schools. Among her many roles in her community Barb is also a language teacher. She has dedicated much of her adult life to creating new speakers of Anishinaabemowin.

The TRC’s report couldn’t make it plainer: Canada’s Indian Residential School System, a church-state partnership between 1892 -1996, actively pursued the cultural genocide of First Nations people.

It is written in a section of the report, “States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institution of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next. In its dealing with Aboriginal people, Canada did all these things.”

Among the plentiful call to action items, number 13 calls upon the federal government “to acknowledge that Aboriginal rights include Aboriginal language rights”.

“If the government really wants to do anything with that call to action they need to pump money into immersion programs,” remarked Barb. “We have speakers of the language that aren’t trained. Create schools to train the speakers to become Early Childhood Educators and teachers. Once we have men and women trained in this way we can open up daycare immersion programs and follow them right up to Grade eight. By the end of Grade eight you’ll have fluent speakers.”

For now, Barb remains cautiously skeptical knowing that the challenge of implementing the recommendations in the TRC report comes with an arduous and dedicated legal and political battle.

“If you don’t have the right people in government believing in this then you’re not going to get any action,” she commented. “If the TRC dissolves because their mandate is complete, this report is just going to become another book on the shelf.”

(feature image, Barbara Nolan -about six years old. Photograph taken at the Indian Residential School in Spanish, Ontario)