“I’ve been fishing here for fifty years- since I was a kid and way before the boardwalk was built, and never seen this before. This is the first fishing season that I’ve seen anything like this and it never stops coming. Sometimes it comes in just like sheets. You can see it hangin’ on the rocks down there.”

The comment is from Saultite and hobby fisherman, Steve Hicks. It’s still summertime and the day is sunny and hot. Hicks is hanging out with a few other fishermen on a pier on the Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario boardwalk – close to the hydro damn. As we speak Hicks leans over the railing and gestures across the St. Marys River indicating long, gooey streaks of a slimy material moving through the speedy current and visibly clinging to the rocks beneath the water surface –‘rock snot’. Or if you can’t bring yourself to the vulgarity, didymo (Didymosphenia geminata).

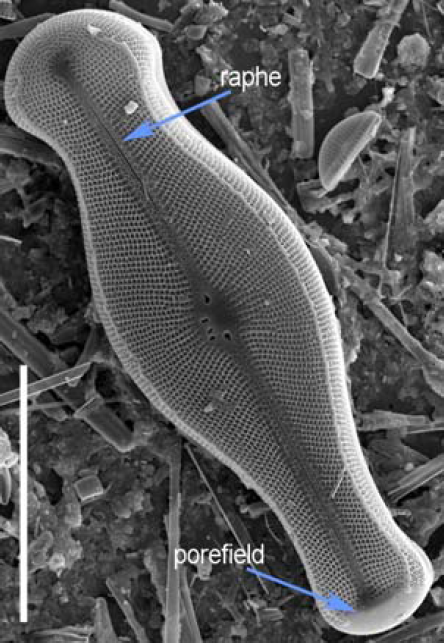

Didymo has the unpleasant appearance of nasal discharge and the texture of wet wool. Didymo, a species of diatom, is a greenish/brownish algae and one that naturally occurs in Lake Superior.

However, a recent article in the Detroit News identified that our southerly neighbours in Michigan have observed large masses along a stretch of the St. Marys River near Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Sarah LeSage, aquatic invasive species program coordinator states that the presence of ‘rock snot’ is a “full-on algae bloom. It’s a totally different scale from anything that we’ve seen before.”

Didymo- a single-celled, silica shelled algae was once pursued by the wealthy for it’s microscopic beauty.

Sharon Moen, Communications Coordinator for the University of Minnesota Sea Grant Program, explained in an interview this week that at one time didymo was a highly sought after diatom- a single cell phytoplankton that forms microscopic colonies taking on an appearance of glass-like zig-zags, fans, ribbons and star shapes, among the wealthy. Not so today where the species has become invasive in places like New Zealand and British Columbia, and more recently appearing as large masses in Lake Superior’s tributaries.

In a 2009 report written by Moen, Doug Jensen, Minnesota Sea Grant’s aquatic invasive species program coordinator makes mention of discovery of excessive algae along a few shorelines in Lake Superior noting that “Lake Superior is typically too cold and too nutrient-poor for algae to thrive en masse.”

However, observations from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and from Sault, Ontario’s own experts- local fishermen, indicate that didymo is indeed present in the St. Marys River though its origin is unconfirmed at present.

As Moen points out when asked about the influence of climate change upon she replied, “Things are changing and it’s hard to know what warmer climates and added nutrients in the water are going to do to the diatom community. Diatoms are sensitive to human impacts however. As far as didymos, shall we say, ‘fall from grace’, that was noted about twenty years ago in British Columbia. That’s when it started getting its name ‘rock snot’.”

After the invasive situation of didymo presented in British Columbia a similar condition transpired in New Zealand’s rivers. Moen’s report How Didymo Became Rock Snot details that it was in 2004 when didymo was first reported in the Southern Hemisphere “when it blanketed roughly 18 miles of river bottom in New Zealand’s Mararoa River.

After the invasive situation of didymo presented in British Columbia a similar condition transpired in New Zealand’s rivers. Moen’s report How Didymo Became Rock Snot details that it was in 2004 when didymo was first reported in the Southern Hemisphere “when it blanketed roughly 18 miles of river bottom in New Zealand’s Mararoa River.

Though extensive scientific exploration is required to determine how didymo has become an invasive species on the other side of the world, and why it is now appearing in Lake Superior’s tributaries, the general consensus among the scientific community points to the unintentional practices of fishermen. Didymo embeds itself in the felt-soled waders, treasured among recreational anglers, and clings to fishing gear.

Above: Despite didymo’s snotty appearance the texture has been compared to wet wool. Below: A piece of didymo -rock snot, drying on the Sault Ste. Marie boardwalk. Didymo takes on the appearance of tissue paper when it dries.

“Fisherman go fishing where there’s rocks and in streams while wearing their felt-soled waders. They are stepping on these diatoms that are sticking into these felt waders and then they may go to a different water body or a different fishing stream or lake and then leave those little diatoms behind,” elaborated Moen.

According to Moen there isn’t an identified solution to stopping the of didymo once it has become invasive, though the scientific community has observed ebbs and flows in the degree of biomass algae blooms once didymo becomes present in unnatural water environments.

“That’s the problem with invasive species,” remarked Moen. “It’s not like tossing a piece of trash out your window. It’s like tossing a piece of trash out your window that can reproduce- a lot.”

In its invasive form didymo can persist for several years though it has been observed that nuisance blooms can taper off after 3- 4 years informs Moen.

Recreational fisherman, Robert Nadeau, regularly hauled up rock snot on his line each day he fished this summer.

Didymo can survive for almost two months out of the water in damp conditions. Moen advised a few prevention strategies that fishermen can employ to prevent the transmission of the algae.

- *Avoid using felt-soled boots, the most likely way didymo spreads.

- *Remove any visible algae from fishing gear and sterilize nets and other field gear before resuse. A thorough rinse in hot water AND/OR a 30 minute soak in a 5% salt mixture (2 cups of salt per 3 gallons of water), followed by a tap water rinse.

- *Can’t bear the thought of giving up your felt-soled boots? Make sure your boots, waders and other equipment are fully dry for five days prior to re-entry into any water bodies. *Drain lake or river water from motor and boat water traps before leaving access.

Though there doesn’t seem to be a direct impact upon human health didymo’s abrasive silica shell can cause throat and eye irritation. However, the potentially invasive spread of didymo poses a risk to a tourism economy reliant upon the draw of freshwater fishing. Further, the impact upon a delicate ecosystem would be imminent.

“It covers everything,” commented Moen. “It’s like putting a wet wool carpet over everything – food, substrate, rocks where small creatures may live and light for photosynthetic plants if blocked out. Much like any invasion, a didymo invasion can create a mono-culture of itself.”

Back in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario Hicks has seen enough of that rock snot. “I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s non-stop every day. And when I come down to fish at night it’s non-stop all night. I was pulling up 10 pounds of it at a time.”

Expanding his arms wide open he adds, “I was pulling off streams of it this big from my fishing line.”

(feature image: Robert Nedeau, fishing on the St. Marys River in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. This summer he caught more rock snot than fish.)