At the centre of North America lying south of Hudson Bay and west of and south of James Bay is the world’s third largest wetland- the Hudson Bay Lowland. This area is the size of Japan and larger than the United Kingdom and Germany, (The World’s Largest Weltlands: Ecology and Conservation, 2005).

In 2002 DeBeers, the world’s leading diamond miner and trader, ventured into Ontario’s Far North seeking the precious stones but instead discovered copper and zinc. Following the discovery other exploration efforts boomed and discoveries of volcanogenic massive sulphide, nickel, vanadium, titanium, platinum and gold were made.

In 2008 prospectors uncovered for the first time in Ontario’s Far North, and anywhere in North America, commercial quantities of chromite. When chromite is processed as an alloy it is used in the production of stainless steel and other products. It is valued for its ability to increase hardness, toughness and resistance to corrosion. Four countries account for 80% of the world’s chromite production- South Africa, Kazakhstan, Turkey and India. Current world resources are sufficient to meet demand for centuries. The lack of North American production makes Ring of Fire deposit attractive however the price of chromite dropped about 60% in past five years.

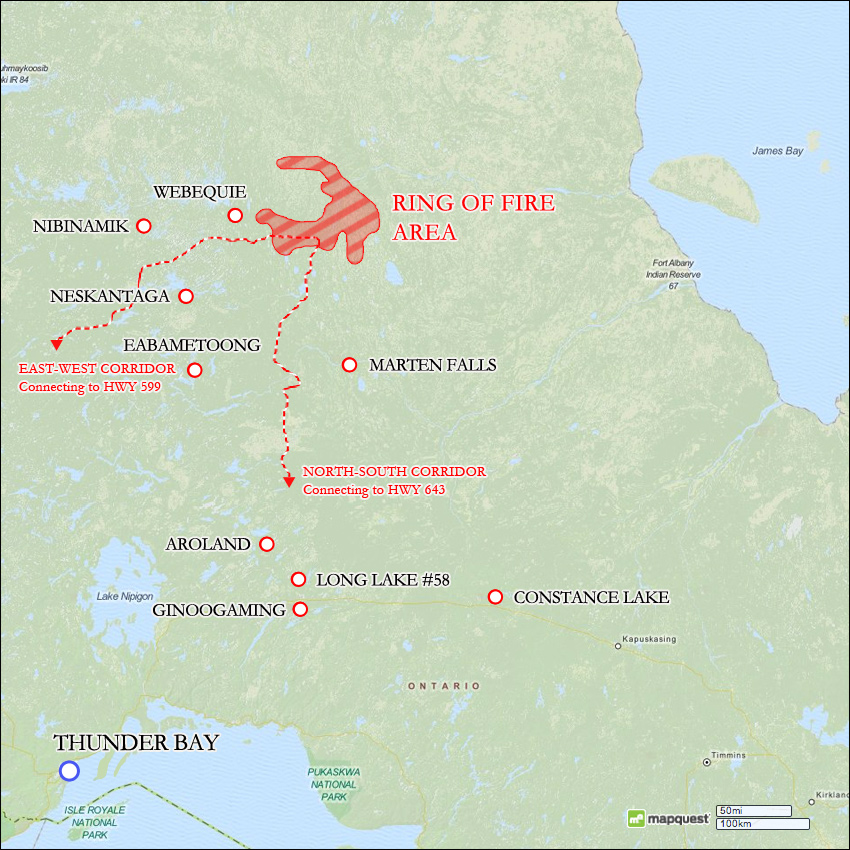

This crescent shaped and mineral rich area is approximately 240 kilometers west of James Bay and 500 kilometers northeast of Thunder Bay and has come to be known as the Ring of Fire. The Ring of Fire encompasses an area of 5 120 sq. kilometers, covering an area slightly smaller than the Calgary Metropolitan Area. Experts say there is enough chromite in the Ring of Fire to meet North American needs for 200 years.

The Ring of Fire’s location in the James Bay Lowlands places it within the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Together, these areas form the largest peatland (a type of wetland) in the world and acts as an important carbon store. Wetlands are a naturally saturated environment, meaning that managing tailings (residue) and waste rock would be particularly challenging. The area also includes six out of twelve of Canada’s major rivers that converge and flow into James Bay.

Ontario’s Far North contains the world’s largest area of boreal forest that is free from large-scale human disturbance. The Environmental Commissioner of Ontario (ECO) describes the Far North as “a stronghold for biodiversity” that includes at-risk animals such as caribou, wolverines and polar bears.

The boreal forest is used by nearly half of the birds in North America each year and contains wetlands that filter millions of litres of water a day. The boreal forest makes up almost one third of the world’s forests, stretching as it does round the northern parts of North America and Eurasia. One third of this forest is found in Canada, stretching more than 5 000 km in length from Newfoundland and Labrador in the east to Yukon in the west, and extending south 1 000 km in length from the edge of the arctic tundra, the boreal region occupies more than half of Canada’s land area.

Development of the Ring of Fire will affect 24 000 First Nations people that are dispersed among 31 small communities who still depend on hunting and fishing to maintain their lifestyle and possess inherent rights to the land. There are 9 First Nations communities most affected by proposed mining developments comprise the Matawa First Nations and include: Nibinamik First Nation, Aroland First Nation, Eabametoong First Nation, Ginoogaming First Nation, Long Lake #58 First Nation, Marten Falls First nation, Neskantaga First Nation and Webequie First Nation.

It is estimated that about 30, 000 claims have been made in the Ring of Fire. Three key players have put forward proposals for development. Noront Resources of Toronto Ontario are developing a $610 million project to mine nickel, copper and platinum reserves. In an attempt to mitigate environmental impact the company is proposing an underground mine.

KWG of Toronto owns 30% of the ‘Big Daddy’ chromite deposit in partnership with the third developer, Cliffs Natural Resources of Cleveland, Ohio. Cliffs is the main proponent in the Ring of Fire.

Cliffs also purchased the ‘Black Thor’, the largest chromite deposit in North America, for $240 million dollars in 2010. In 2012 observers cautiously estimated that the combined Noront and Cliffs project could spend up to $1.3 billion dollars on the project and create more than 1 000 jobs between the mining site and production facility in Northern Ontario. This cost did not include the expense of transporting materials back and forth which could be estimated as high as $2 billion dollars. The direct economic benefit alone would be close to $3.5 billion dollars.

Cliffs also purchased the ‘Black Thor’, the largest chromite deposit in North America, for $240 million dollars in 2010. In 2012 observers cautiously estimated that the combined Noront and Cliffs project could spend up to $1.3 billion dollars on the project and create more than 1 000 jobs between the mining site and production facility in Northern Ontario. This cost did not include the expense of transporting materials back and forth which could be estimated as high as $2 billion dollars. The direct economic benefit alone would be close to $3.5 billion dollars.

In a March 2014 report prepared for the Parliament of Canada indicates that the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC) suggests that the Ring of Fire could contribute $5.1 to $10 billion to the province’s GDP in the first 10 years and $14.4 to $27 billion in the first 32 years.

The report goes on to state that Ring of Fire projects would also have an impact outside Ontario. In the first 10 years, the GDP impact outside Ontario would range from $2.1 to $6.3 billion; in the first 32 years, the GDP impact outside Ontario would range from $5.8 to $16.8 billion. The OCC report also estimates the tax revenue that Ring of Fire projects would generate. In the short term, $870 to $940 million would accrue to federal reserves. In the long term, the federal government would receive $2.89 to $3.25 billion in taxes.

However, facing internal pressures to sell off its Canadian interests as well as ongoing barriers, Cliffs suspended operations on the chromite project after the fourth quarter in 2013 stating, “The Company determined that it will not allocate additional capital for the project given the uncertain timeline and risks associated with the development of necessary infrastructure to bring this project on line.” The company will close its Thunder Bay and Toronto offices, but will continue its work with the provincial government and First Nations on the infrastructure issue.

The lack of a transportation route to the site has been a major barrier, in particular an all-weather road, in developing projects in the Ring of Fire. The company had been seeking financial support from the Ontario government to build a 340 kilometer road that cut through wetlands, rivers and the boreal forest. The Liberal government has said that they would be willing to commit 1 billion to develop infrastructure that could be used for either roads or rail.

The Ring of Fire Regional Framework Agreement was signed in March 2014 between the Matawa Chiefs Council and the Ontario government. The Ring of Fire Regional Framework Agreement is intended to ensure a community based approach among the nine members representing the Matawa Chiefs Council and the province when developing the mining project in Northern Ontario. The plan allows the First Nations to collaborate around priorities that include environmental monitoring, resource revenue sharing and infrastructure.

However, the announcement by the Ontario government this past August regarding a newly formed Ring of Fire Development Corporation has some First Nation Chiefs frustrated. The Corporation is an interim board, made up of four Ontario public servants. There is not any representation of First Nations on the board at this time. Earlier this year, the Matawa Chiefs Council wrote the Premiere requesting that Deloitte, the firm hired to assemble the development corporation, be released from its contract. The Chiefs Council stated that it was prepared to discuss options for a developmental corporation with the province.

The Chiefs Council has addressed several letters on the matter to the Minister of Northern Development and Mines, Michael Gravelle. Gravelle responded stating that the province is motivated to work with the First Nation communities and according to one CBC report that the “announcement was necessary to meet an election promise and to appease ‘other interests’.” Other interests could be industry pressures in moving ahead with Ring of Fire projects.

Gravelle commented, “The process we put in place through the modernized Mining Act, assigns some time lines that ensure, from the perspective of industry, a predictable and confident mineral exploration environment in Ontario.”

In the same CBC report, Gravelle also added insult to injury when one of the Matawa Chief Council members, Chief Peter Moonias of Neskantaga First Nation, expressed alarm over pending exploration permits stating that they are a violation of the Framework Agreement. Gravelle remarked that the permitting process had already been delayed for a year while Neskantaga First Nation dealt with a suicide crisis.

Neskantaga is a small fly-in community and home to about 400 people. In 2013 Neskantaga First Nation declared a state of emergency after 7 youth took their lives in the period of one year. In the same year 27 youth attempted to commit suicide. Since the declaration, 3 more young people have committed suicide.

Addressing the media in April 2014 Chief Moonias stated that “the suicide crisis is a direct result of the fourth world living conditions in his community” impaired by illness from contaminated drinking water since 1995, lack of housing, mould, food insecurity and lack of inadequate health services.

Chief Moonias has also noted with significance that, “The development of the Ring of Fire will allow my community to become self-reliant and self-governing.”

On August 22, 2014 Neskantaga cut the ribbon at the opening of a new state-of-the-art training centre that may help the community envision a more hopeful future. The Ontario government funded the centre that will prepare the people of Neskantaga for the jobs that the Ring of Fire will bring to the area. There isn’t a high school in Neskantaga and prior to the opening of the centre those seeking an education beyond grade 9 had to travel to larger urban areas to do so.

Concerns regarding the environmental impact have been expressed by numerous bodies and caution that development should not be rushed until thorough research of the region’s environmental resources and impact studies have been conducted.

In their Fall 2013 newsletter, the Wildlands League state that, “Any transportation corridor would have major environmental impacts since it would bisect largely intact wilderness, populated by caribou and other species highly sensitive to disturbance, and cross many rivers and streams. The right-of-way, and excavation elsewhere for gravel, could interfere with wildlife migration since animals employ higher, drier ground for traveling. It could also act like a dam, impeding west to east drainage in a relatively flat wetland-dominated landscape. Public access would open up pristine areas for hunting, fishing, tourism, logging and other activities.”

Interestingly the Far North Act, established in 2010, set out to preserve the area that is home to 200 sensitive species of animals that include the aforementioned caribou, wolverines and polar bears as well as bald eagles and beluga whales. The Far North is considered to be one of the world’s largest remaining intact ecosystems.

The goal of the Far North Act was to guarantee that First Nations had a greater say in the area’s future, protection and a greater share in its possible prosperity. Many First Nations believe that the Far North Act does just the opposite and assert that they were not fairly consulted during the process leading up to the Act.

The Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) is a political territorial organization representing 49 First Nation Communities within Northern Ontario. NAN has stated that the Act, “Appeared to be the product of discussions between the government and certain conservation organizations fixated on protection of the boreal forest in northern Canada, which was identified by Global Forest Watch Canada as the last of the world’s remaining intact forest landscapes.”

Critics of the Act, that include politicians, First Nations and other organized entities, say that the Act: allows government to decided how to use resources; removes 50% of the land mass of the Far North from potential economic opportunity; and was developed with limited consultation with Northerners. The Act protects huge swathes of land in effect trapping First Nation communities within certain boundaries.

The Act establishes a land use policy agreement that is open to First Nation input but the province can veto all elements of land use. NAN stated, “Even if a land use plan is “agreed” to, First Nations will not acquire any special development rights to the off-reserve territory left over. First Nations will still be subject to legislation like the Ontario Mining Act that do not give them any kind of preferential treatment or any assurance of benefit sharing.”

Brian Davey is the executive Director of the Nishnawbe Aski Development Fund. In the Fall 2014 edition of Onotassinijk Magazine, Davey encouraged First Nation communities to keep their eyes wide open when planning for the inevitable tidal wave of development in the Ring of Fire that will wash across the Far North.

His closing thought perhaps best summarizes the Ring of Fire’s economic magnitude and the role of the First Nations in the process. “The vision is First Nations prosperity and there are many different ways to achieve that end. In regard to the larger community, prosperity in the First Nations community means prosperity for northern Ontario as a whole by virtue of the principle of interdependence. Ultimately, our success in generating wealth will not only be felt locally but will reach throughout the province and across the country.”