Editor’s Note: Original date of publication January 8th, 2013

It’s the day before New Year’s Eve and it’s coming on dusk. Outside it’s cold, northern Ontario cold. The air is so icy that your frosted words snap off at the end of your lips. We’re bumping north up Goulais Avenue in Shannon’s SUV and heading to Nettleton Lake. It was her brother’s favourite place. Over the radio ‘If I Die Young’ comes on. Shannon flashes her eyes, filled with concern, to the rear view mirror.

“Mom. Are you ok?”

“Oh jeez yeah. Just leave it on but I might start cryin’ again.” Sandra chuckles briefly. She has a throaty laugh but these days it’s hard to come by. Her eyes are bloodshot. A lot of tears were shed this afternoon.

*****

Scene of the crime, located at the centre of the Sault Ste. Marie’s ward 2. This ward experiences the highest amounts of crime in the City.

January 8th, 2013 marks the second anniversary of 29 year old Wesley Hallam’s gruesome murder in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Four days after his murder, two young boys walking along Landslide Rd. discovered Wesley’s decapitated and dismembered body that had been dumped into a deep ridge along the side of the road.

After a relentless investigation by local police, Ronald Mitchell, 27 yrs., Eric Mearow, 27 yrs., and Dylan Jocko, 28 yrs., were charged with first degree murder and being a party to indecently interfering with Wesley’s remains. Forensics determined that Wesley was murdered January 7th or 8th 2011, during a house party at 30 Wellington St. East.

I arrived at Sandra’s home earlier that afternoon. She swung open the screen door and pulled me in out of the cold. She was smiling and that meant that her bright blue eyes disappeared, instead replaced by twin rainbows that sat atop the apples of her cheeks.

This wasn’t the first time I met Sandra. We got together a few weeks earlier to discuss today’s visit. And of course I had observed, from a respectful distance, Sandra and her daughter, Shannon, during autumn’s preliminary trial regarding Wesley’s tragic passing. Shannon arrived shortly afterwards and Sandra’s mom, Jackie, joined us. We broke the ice for a while and then went outside so that I could meet Bob, Wesley’s grandpa.

Bob is a soft spoken gentleman with a grandfatherly beard. He doesn’t seem to be expecting us when we crash his refuge. The garage is toasty warm. Bob is sitting on a porch swing and curled up next to him is Chummy, a border collie with a thick black coat.

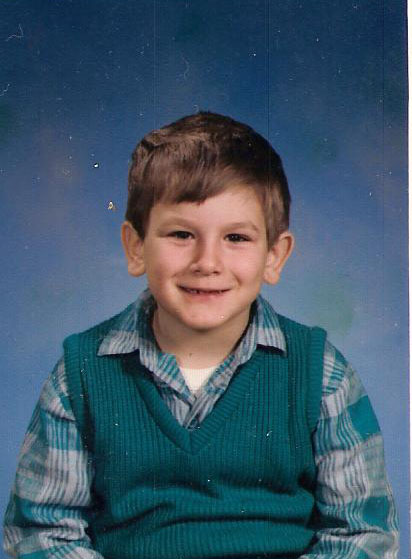

Bob and Jackie were very close to Wesley. Both Wesley and Shannon spent a lot of time with their grandparents. With some difficulty Bob shares a few memories of Wesley as a little boy.

“He caught his first fish with me. I took him to Ranger Lake. We have a picture. It was a grey trout,” he pauses. “We certainly miss him. He was raised here. We’ve got pictures though…,” his voice trails off. Bob looks away. His eyes are glassy. His mouth becomes a tight line beneath his beard and his chin quivers.

When he continues his voice is a bit stronger. “What I can’t figure out is why that house on Wellington St. is still there. That place should be closed up. There were gangs in there. It’s not right.”

Bob is onto something.

Accessing annual crime data from Statistics Canada for municipal police services, Maclean’s reported that during the year 2011, Sault Ste. Marie ranked 5th overall among Canadian cities with the highest rate of homicide per capita.

Local statistics for the same year collected by Sault Ste. Marie Police Services indicate a swell of criminal activity within division two of the city. This downtown division is marked by Pim Street on the East, Huron St. on the West, St. Mary’s River on the South and Wellington St. on the North.

In a 13- month period from January 1st, 2011 to February, 2012 police services received 7,273 callouts for division two that included: 4 homicides; 21 sexual assaults; 157 assaults; 34 assaults causing bodily harm/or with a weapon; 4 assaults of a police officer; 164 break-ins; 483 thefts under $5,000; 36 fraud; 191 mischief; 251 bail violations/breach of probation/court absences; 16 arsons; 262 domestic disturbances; and 257 noise complaints.

Wesley was murdered on Wellington St. East just at the top of Gore St., the centre of division two. Increased rates of crime in this area may be attributed to high vacancy rates in the downtown core and more businesses re-locating to the north end of the city. Moreover, elevated crime rates in this neglected end of town can certainly be linked to a vibrant drug culture that flourishes among the abandoned buildings and higher occurrences of poverty in the area.

As we head back into the house Jackie speaks with such tenderness about her grandson. “My husband spent a lot of time with Wesley around here. He was such a great kid. He was very lovey and cuddly when he was little. That last day we saw Wesley he came in the house and gave his grandpa a big kiss. And that’s something special. Bob is English and doesn’t demonstrate affection that way.”

Jackie laughs and her voice, soft, says, “I rocked Wes until he was too old to rock. He loved being rocked to sleep and having his hair played with…”

“Oh yeah,” Shannon cuts her off. “That only ended two years ago.” We all burst into laughter. The moment is bittersweet.

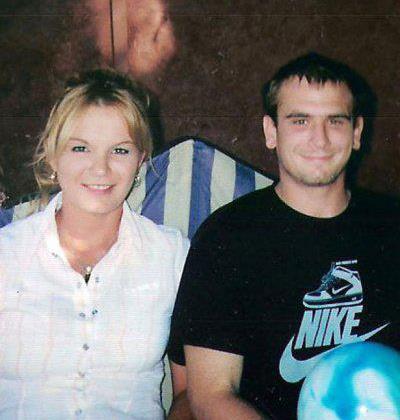

Shannon smiles. It’s the same smile as her mom, little rainbows. “I never thought that I’d have a brother that old that was still so affectionate. He was always giving us hugs and kisses and he was always messing up our hair. He was very affectionate.”

Jackie giggles. “I remember too, on that last visit when I was looking out the window. Wesley was out there keeping Bob company and on his way back in he scooped up Sandra’s little shih tzu puppy. He was kissing her and cuddling her up to his cheek.”

“People didn’t know that side of Wesley, how loving he was,” Sandra smiles. “He loved to give bear hugs. And every now and then a good old fashion noogie.”

“And he never said a bad word about anybody.” Jackie proudly nods her head once as she says this.

“That’s right,” Shannon added. “You weren’t allowed to say a bad thing about anybody. He always found something good to say about someone.” Shannon’s pretty face lights up. She shares her last memory of her brother.

“He just dropped in on me that Friday. He came in and flopped on the couch and said, ‘Oh Shaaan! I’m starving can you make me a sandwich?’ So I made him a grill cheese and ham sandwich and he ate it up. And then he said, ‘Oh, you make the best sandwiches. Can you make me another one?’ So I did.” She has a big smile as she’s telling the story, perhaps harkening back to the image of Wesley sprawled on the couch with a plate of sandwiches balanced on his belly.

“He laid around for a while and we talked. Before he left he gave me a hug and a kiss, told me that he loved me and messed up my hair a bit. I’m glad I had that with him.”

It’s so painful for Sandra to remember her son out loud. When she is recalling moments of her boy’s life she often weaves in and out of the past and present. “Wesley and I took his son shopping on January 3rd. We had a cart full of stuff, whatever he wanted, including a four wheeler. When we brought him back home he said, ‘Mommy! Daddy wants me to go to a Blue Jay game with him’.” Sandra is tearing up. “That’s one of the most heartbreaking things. He’s waiting to go to that Blue Jay Game with his Daddy.”

When Wesley’s was killed his son was just five years old.

Since Wesley’s murder the media and community members have posthumously burned him at the stake. The family doesn’t deny the Wesley had a history with the law but the claims against him have been brutal and often ignorant.

For their part in Wesley’s murder, Melissa Elkin and Kayla Elie were charged and found guilty of being an accessory after the fact, interfering with a dead body and obstructing police. They are both walking free today. Jaclyn MacIntyre was similarly charged but remains in custody. It is difficult for the Hallams to think about the two non-consecutive years Wesley spent paying his time in jail.

“My brother served almost two years for menial things as well as a few assaults. It makes me sick that these two women are walking around free today. My brother was murdered.”

“He spent so much time in jail. They don’t rehabilitate anybody. So when he got out he didn’t know where to go or what to do. So that’s where he’d end back up again. I see a pattern. I always thought that for my brother if they taught him a trade or something then maybe he wouldn’t have reoffended. It was all he knew.”

There are over 72, 000 people that live in Sault Ste. Marie but the community feels much smaller. If you don’t know somebody then they’re at least a familiar stranger. It’s also a place where your past sticks to you. People don’t forget in the Sault.

“He had to get out of town. He couldn’t do that lifestyle anymore so he moved down south. He had a job in a potato factory.” Sandra pronounces potato ‘poh-taa-dah’. Everyone laughs.

“He liked that job. He loved working. People don’t think he had anything in him but he did. He was waiting for a superintendent position in an apartment building. He was making a new start for himself. But then I asked him over and over again to come home for Christmas. I’ll never forgive myself.”

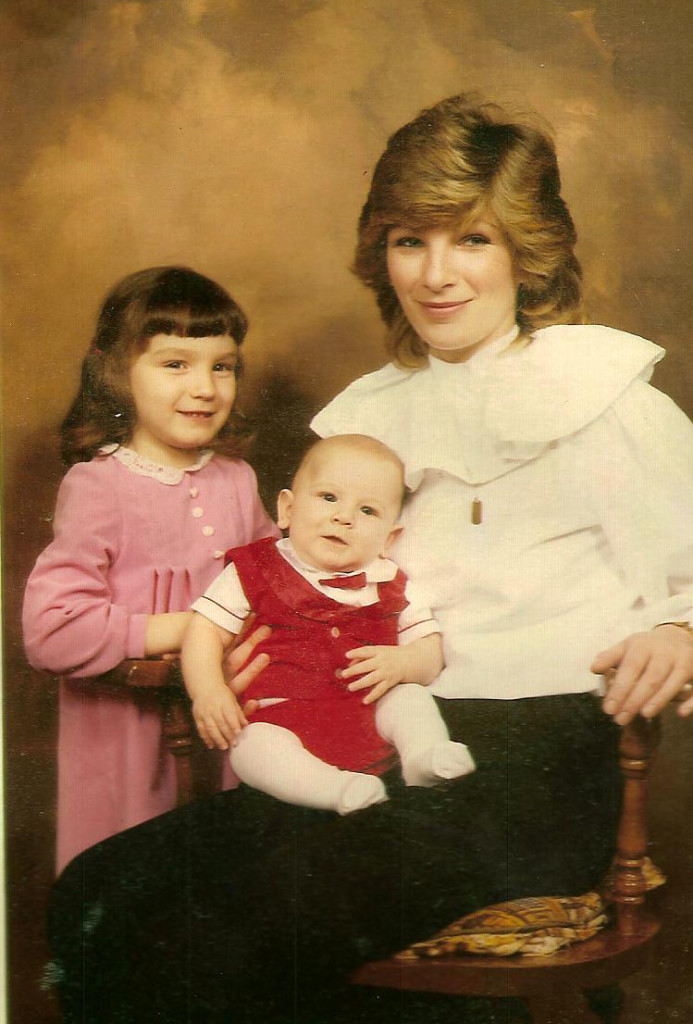

Mom- Sandra Hallam and her two children. Shannon is about 3 years old and Wesley is about nine months old.

Sandra is weeping, unable to go on. Shannon comforts her. “It’s ok mom. You’re doing good. You haven’t talked about anything in such a long time.”

Sandra begins to wail and moan. It is the sound of a mother who has lost a child. She is in agony. “How can I go on when I hear him in my head screaming ‘help me!’. I just want to go away and cry.” She is choking, gasping for breath. “No one knows…I have to pretend that I’m ok all the time and I want to cry. I want to cry so bad because I’ll never see my son ever again. My poor baby….”

Even though it has been two years since Wesley’s passing the grief is still fresh for everyone. It is not unusual for co-victims of murdered loved ones to be stuck in a perpetual loop of horror and mourning.

The Canadian Parents of Murdered Children writes, “Society offers many misconceptions about grief. Many people believe it is a lineal experience where the bereaved person goes through various ‘stages’ of their grief, eventually reaching some kind of ‘acceptance’.

When a homicide occurs, the family’s grief is often worsened by a seemingly drawn-out legal process, of bail hearings, preliminary trials, adjournments, mental health assessments, more adjournments and perhaps finally the trial. For families bereaved by homicide, the constant involvement in the investigation and the legal process creates a situation where survivors of homicide victims re-live the horror of what has happened to their loved one.”

Two years later and the courts have stalled halfway through the preliminary hearing. But perhaps most heartbreaking is that the family still hasn’t been able to say good-night to Wesley. Parts of his body have not been cremated and won’t be until his flesh is no longer needed as proof of evidence.

It was Shannon who identified her brother’s remains. Even though his killers did their best to defile Wesley’s body beyond recognition, Shannon was still able to identify her brother by a tattoo on his arm.

“I just want to know if they feel any kind of remorse. Do they feel anything? From what I see they don’t. And they deserve a different punishment than other people because what they did was disgusting. It was inhuman. Animals act like that, not people.”

Shannon, who has been a rock for the family, is sobbing now. “It’s just been so hard. There’s such anticipation about what’s coming ahead. You don’t think it’s ever going to end. I just want him to …rest.”

*****

We’ve arrived at Nettleton Lake. Sandra and Shannon are cheery. They’re happy to be here, where Wes loved to be.

Shannon and Sandra follow a short trail to the lake. They’re hanging on to each other trying not to topple off the path into the snow. The sky is beautiful, purple and navy blue. Shannon and her Mom are standing in front of the lake laughing and hugging. The moment feels good.

After taking a few pictures we head back to the car. This time Sandra losses her footing and Shannon goes down with her. They sit in the snow for a while, unable to get up, giving over to uncontrollable laughter.

When we finally reach the car, Shannon brings out the bottle of Budweiser that she had brought along. It was her brother’s usual. She twists off the cap, holds the bottle up and says, “To Wesley!” It’s a toast. Everyone takes a swing. The bottle makes its way back to Shannon. There’s a mouthful left.

She turns around and looks back across the lake. She’s quiet for moment. “This is for you Wes.” She throws the bottle into the trees. “I love you.”