Every view of the world that becomes extinct, every culture that disappears, diminishes a possibility of life. ~ Octavio Paz, 1914- 1998

There are some things that can never be recovered once they are lost or ripped away from us. Barbara Nolan is doing all that she can to preserve her beloved ancestral tongue. This spunky 68 year old Elder is a vibrant speaker of her first language- Anishinaabemowin, and she is deeply compelled to create speakers of the language.

Barbara Nolan -about six years old. Photograph taken at the Indian Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. “You lose quite a bit. They try to take your language. Some lost their identity and a sense of who their family was- the connection is lost.”

Barbara Nolan -about six years old. Photograph taken at the Indian Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. “You lose quite a bit. They try to take your language. Some lost their identity and a sense of who their family was- the connection is lost.”

Like so many of her People and generation, Barbara is a residential school survivor. When she was five years old and her sister was six, Barbara’s parents packed the little girls into the car and headed to Spanish, Ontario where the nearest residential school was located.

“We were happy, we were going to school. We didn’t know that our parents were going to leave us there. When we got there me and my sister were in awe. The floors were so shiny.” Barbara extends her arm slowly towards the ceiling, “And the walls were so nice and there was a big statue there – but we didn’t know what it was.”

We are sitting at Barbara’s dining room table in Garden River, Ontario. She is a soft-spoken lady. Her voice is calming even in the telling of such a distressing memory.

“We were just admiring the place and I guess my parents must have just stepped out quietly. And then we turned. And then we looked for our parents. And then these nuns came and we cried. Then we were told not to cry. Then we didn’t know what they were saying. Then we got scared. And then we started talking to each other in the language. Then we got hit for speaking our language. You don’t speak your language there. I received a lot of strappings over the four years I was there.”

Though they would try, not one person in that oppressive and abusive institution could beat the Anishinaabemowin language out of the tiny five year old.

Findings from the 2011 Census of Population and the 2011 National Household Survey indicate that:

- 213,490 people reported an Aboriginal mother tongue

- Many Aboriginal languages were reported as mother tongue by less than 500 people

- Cree languages, Inuktitut and Anishinaabemowin were the most frequently reported Aboriginal languages

- 19, 275 people said that the Anishinaabemowin language was their mother tongue, 34, 110- Inuktitut and 83, 000 – Cree

- One in six Aboriginal people can conduct a conversation in an Aboriginal language

- More than 52,000 Aboriginal people were able to converse in an Aboriginal language that was different from their mother tongue, suggesting that these individuals acquired an Aboriginal language as a second language

- Among the population reporting an Aboriginal mother tongue, 82.2% also reported speaking it at home

Barbara has been invested in saving the Anishinaabemowin language for over forty of her professional years.

She returned to her home in Wikwemikong First Nation at the age of 9 yrs. to complete her elementary education and then attended high school in North Bay. After her high school graduation Barbara headed to Toronto with her trendy beehive and snappy pointed high heel shoes having landed a good job with Shell Canada in their Accounts department. She met her husband there and returned to his home in Garden River, Ontario in 1972.

Barbara was immediately hired with the Roman Catholic School Board as a family counsellor. While working at St. Hubert’s school the principal came to her concerned that their First Nation students were performing poorly in their French language classes. Barbara took to the schoolyard at recess time to get to the bottom of these low grades. “Miss?” the students addressed her. “Why do we have to take French? We should be learning to speak Anishinaabemowin.”

And Barbara decided to make it so.

1972- Barbara is 24 years old and working with the Sault Ste. Marie Separate School Board. While working at St. Hubert’s School as a Family Counsellor, Barb would make history bringing Native as a Second Language into the elementary school system for the first time anywhere in Ontario.

1972- Barbara is 24 years old and working with the Sault Ste. Marie Separate School Board. While working at St. Hubert’s School as a Family Counsellor, Barb would make history bringing Native as a Second Language into the elementary school system for the first time anywhere in Ontario.

She approached the principal and said, “Let me put a proposal together so we can teach Anishinaabemowin as a second language.” The principal agreed that it was a good idea and Barbara got busy. The proposal went to the Ministry of Education. And it was approved. Then she thought to herself. “Oh no! Now we need a teacher!”

Back in her dining room Barbara said with quiet pride, “It was the very first Native as a Second Language program offered in Ontario. Other schools followed suit. But it stemmed from the proposal I wrote for St. Hubert’s School.”

Barbara borrowed the French curriculum to adapt a Anishinaabemowin language program and taught the native students at St. Hubert’s until a teacher was hired- all while maintaining her regular position with the school board as a counsellor.

Barbara was called to teach. Throughout the course of her entire career Barbara frequently taught in the immersion language programs. During the summers she worked at Bay Mills Community College in Michigan where she taught Anishinaabemowin immersion programs. In the mid ‘80’s she accepted a position at Sault College of Applied Arts and Technology as a student counsellor. She took an early ‘retirement’ in 2003 and has a schedule that is committed to leading culturally relevant classes. Today she is works as a Cultural Advisor at Sault College on a part-time basis and two days a month at Algoma University College.

And even when she is not employed in a teaching capacity Barbara still teaches. It is simply her nature to share her knowledge, to nurture others.

In her ‘off’ time she teaches an immersion program at Sault College made possible by temporary funding provided through Employment and Social Development Canada. Her students are comprised mostly of Elders.

Of her students Barbara shared, “Some may have gone to residential schools. Not all of them, but some of them. When they left the residential schools they went home, became of childbearing years and raised kids. In the residential schools they were told that their language was bad. And they never passed it on to their children.” Her face crumpled and then she whispered, “Much like myself.”

A language is endangered when its speakers cease to use it, use it in an increasingly reduced number of communicative domains, and cease to pass it on from one generation to the next. That is there are no new speakers, adults or children[1]. There are over 50 Indigenous languages in Canada and only three are expected to survive: Cree, Anishinaabemowin and Inuktitut.

| Degree of Endangerment | Speaker Population |

| safe | The language is used by all ages, from children up. |

| unsafe | The language is used by some children in all domains; it is used by all children in limited domains. |

| definitively endangered | The language is used mostly by the parental generation and up. |

| severely endangered | The language is used mostly by the grandparental generation and up. |

| critically endagered | The language is used mostly by very few speakers, of great-grandparental generation. |

| extinct | There exists no speaker. |

Source: UNESCO

UNESCO’s Atlas of the Worlds Languages in Danger considers a language endangered if it is not being learned by at least 30% of the children in a community. The 2001 Canadian Census (Norris, 2003) indicates that only 15% of Aboriginal children in Canada are learning their Indigenous mother tongue, a decline from 20% in the 1996 census[2].

Enduring all spectrums of abuse, in addition to being stripped of their culture and language, has left many residential school survivors struggling to reclaim their identity. This effect can be passed on to the next generation. However, people like Barbara are a living testament and powerfully demonstrate that the resiliency and heritage ofFirst Nation Peoples is greater than the legacy of residential schools.

Though most of the Anishinaabemowin speakers are of the grandparental generation, the Anishinaabemowin language has not yet been lost.

It is well known globally that prior to colonization indigenous languages were a spoken language only. After failed attempts to wipe Indigenous People off the face of the earth, colonizers strategized ways to assimilate the native culture through the diffusion of Westernized communicative strategies – such as the creation of a phonetic Anishinaabemowin double vowel system.

Barbara teaching at her Anishinaabemowin immersion class at Sault College. “There are some that are ready to speak but you can’t force them to. It will come in time.” Interesting to note- Barbara who was quite soft-spoken in her home becomes quite a lively and exuberant teacher in the classroom! Buckle up!

Barbara teaching at her Anishinaabemowin immersion class at Sault College. “There are some that are ready to speak but you can’t force them to. It will come in time.” Interesting to note- Barbara who was quite soft-spoken in her home becomes quite a lively and exuberant teacher in the classroom! Buckle up!

Despite the educational system’s best intention to contribute to native language revitalization efforts, the formalized and unfamiliar instruction of the Anishinaabemowin language as a written and read curriculum are Western impositions that set back progress around Ancestral Language Acquisition.

After seventy years or so one might expect to get a little recognition for their knowledge- Barbara doesn’t however. But she did express how frustrating it was – especially having learned fluent English through assimilation, or rather- ‘immersion’ (whatever one prefers) in the Residential School Institution, when her lived knowledge about acquiring fluency in any language is rebuffed.

“The school system today want you to teach the four communicative concepts- listening and speaking, reading and writing. Well, we were never a reading and writing tradition. We listened and we spoke. That was it.”

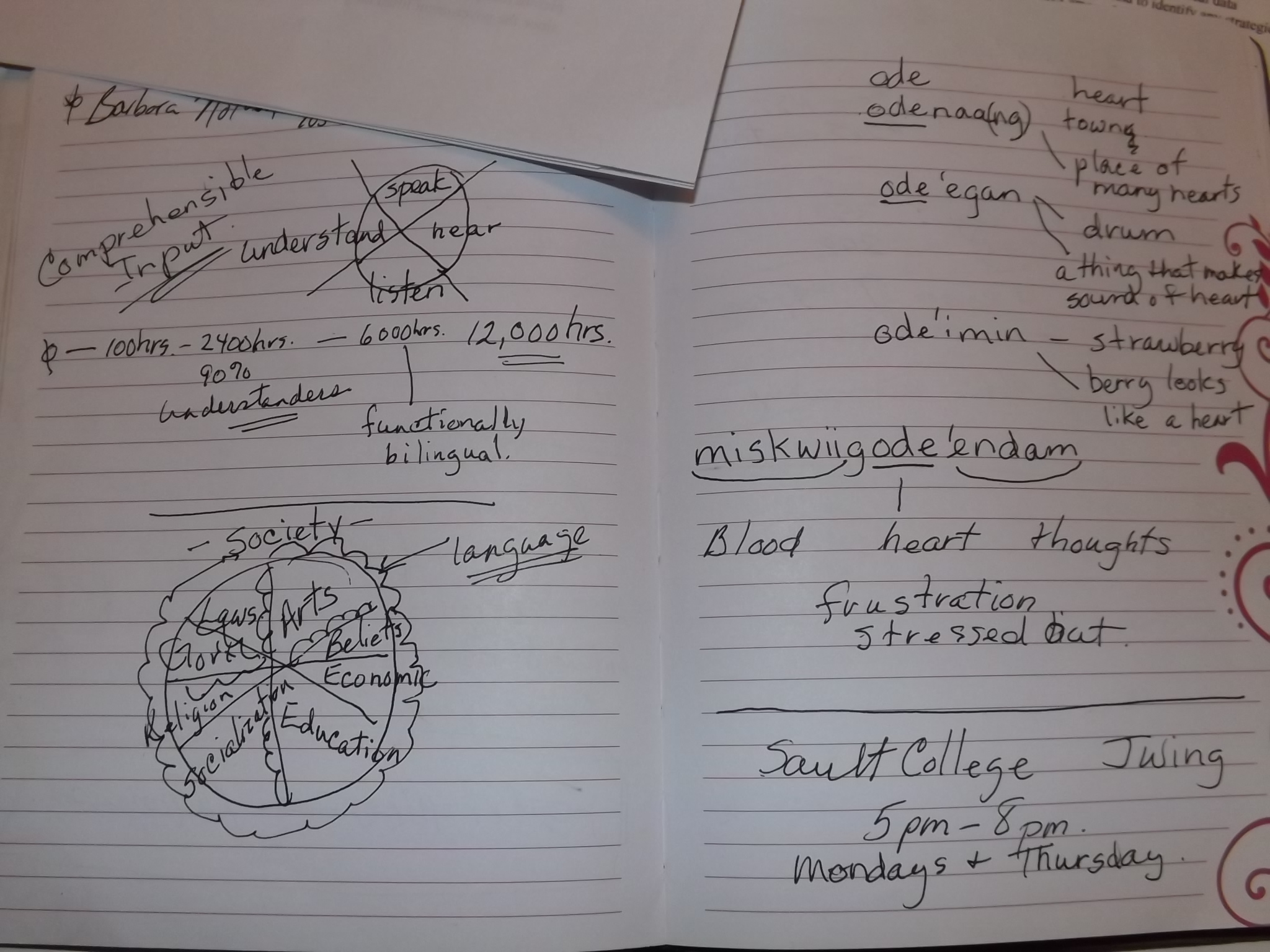

Language is steeped in tradition and culture for the Anishinaabemowin. In true teacher form Barbara reached across the dining room table to borrow my notebook and pen so that she could illustrate the process of language acquisition.

“First you have to hear the language, then you have to listen to what is being said. After that comes understanding the language and then speaking the language. The schools want you to speak and repeat first- they are doing it backwards.”

Birth to three years of age is a critical time for children to lay the foundation of sound making and language acquisition is easier for young children[3]. Much of the patterns of speaking in the ancestral language have been carried over and continue in the First Nations use of English.

Important metalinguistic aspects that would be important factors in ancestral language learning, including, turn taking, narrative pauses, narrative form, appropriate social speech requirements (such as kinship or elder respect, etc.), which come from the ancestral language, are already present in the English that First Nations currently speak. Present also are the factors of the language heritage, geographical familiarity, and pre-eminence that are intricately associated with learning the ancestral language.” [4]

Barb at the Idle No More demonstrations in 2013. “The oppressed are waking up and they want out.”

“Language should be started at home. But a lot of our people don’t speak the language anymore. It is because of the residential schools,” said Barbara. “Now they have to go somewhere outside of the home to get the language. If it can start early, the best and the next place would be daycare – much like the Maori’s did with their language nests.”

It is believed that the Maori People arrived in New Zealand sometime before the 14thcentury.[5] They settled and developed a distinct culture. Inevitable contact with European’s would not occur for another 500 years. Their language, their culture would nearly be eradicated but since the 1980’s the revitalization of the Maori language became an intense national focus. During that time ‘language nests’ were offered to preschool aged children (0-4 yrs. old) where only Maori was spoken. According to the Ministry of Education in New Zealand, in 2006 there were approximately 9,493 children enrolled in a language nest. Afterwards, children move into the elementary system where Maori is instructed through full immersion practices or as a language course.

According to a report by Al Jazeera, “the proportion of Maori people actually speaking the language is now around 25 per cent – up a few percentage points since the early 1980s. It might look like a meager result, but according to linguist Christopher Moseley it should be considered a success.” “Compared to how quickly a language can disappear, in just one generation in extreme cases, the figures are good,” he says. “They are actually quite encouraging.”

The 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples concluded that continuity of a language is dependent on it being used on a daily basis, ideally as the primary home language[6]. Regarding children, when the option of learning from a parent or primary caregiver is not possible, the next best alternative is for the child to participate in language immersion programs. If children are given the opportunity to attend early childhood heritage language immersion programs such as language nests they will have a chance to acquire their heritage language in addition to English at home[7].

Barbara has longed for local language nests. “If we could get full-time speakers in daycare that would be ideal. In the Great Lakes area there are only three or four places that have daycares that are total immersion. So by the time they get out of there the kids speak the language. But they need someplace to go afterwards so you may as well continue it on through all the grades.”

It is not unhopeful that the parent generation, or adults, can acquire their ancestral language. A significant number of Maori who are fluent speakers came to the language as learners. The challenge is the commitment required by adults to acquire their forgotten language.

“You know,” Barbara chuckles. “Adults have a lot of responsibilities. Babies don’t have jobs, they don’t have bills to pay. They don’t have to go to school. They’re just babies. That’s the difference. Adults have to squeeze in whatever time they have left in the day to give to learning a second language. But it is possible.”

Barb met John Paul Montano when she was teaching Ojibwa immersion programs at Bay Mills College.

“JP thirsted for the language. He wanted to become a speaker. So I put my energies towards that. That was 10 or 12 years ago. Every chance I got we met up and we would spend a few hours in the language. We’d go for rides or walks and we’d talk about everything. And now he is a speaker and a teacher of the language.”

So grateful for the gift of his ancestral language JP helped Barbara establish a website- barbaranolan.com, that has enabled Barbara to develop instructional language videos- and it’s all done through storytelling.

Language vitality -or the presence of a language, is not only determined by how often a language is spoken and by how many people it is spoken, but also how the language is perceived by the People. Perceptions are influenced by the attitudes held by outsiders to the culture as well as within one’s own cultural group.

In a report prepared by UNESCO about language endangerment it is stated that, “Internal pressures often have their source in external ones, and both halt the intergenerational transmission of linguistic and cultural traditions. Many indigenous peoples, associating their disadvantaged social position with their culture, have come to believe that their languages are not worth retaining.”[8]

There has been a revived interest among the younger generation to reclaim their language. “Our young people are rising up against the oppression and are showing that they are proud of who they are and of their culture,” Barbara exuded. “But I am fearful that we are not doing enough to save the language.”

Maintaining the language may become a race against time if active efforts are not pursued to increase learning opportunities for a new generation of learners. A language without children is in great jeopardy of being lost.

“We need to create more speakers. We need more immersion programs. And we need more speakers to begin speaking the language so that people can start hearing it again, and listening to the language and then understanding the language, and then become an Anishinaabemowin speaker one day,” said Barbara reinforcing every point with a gentle thump with the palm of her hand on the dining room table.

Returning to my notebook she took up a pen and illustrated as she spoke. “Society is made up of many things- arts, beliefs, economics, education, socialization, religion, government and laws. And you might ask- where’s language in that circle? Well, language is all around that circle- it surrounds everything and it is in between everything. What the government tried to do with Aboriginal people was to try to make us like them. They wanted to take away our Indianness. The best way to kill a culture is to kill the language. Language is everything.”

*****

[1] United Nations, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organizations. “Language Vitality and Endangerment.” http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/doc/src/00120-EN.pdf

[2] McIvor, Onowa. “Building the Nests: Indigenous Language Revitalization in Canada Through Early Childhood Immersion Programs.” Diss. University of Victoria, 1998.

[3] Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples, 1996. “Gathering strength: Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services.

[4] White, Fredrick. “Rethinking Native American Language Revitalizaion.” American Indian Quarterly 30 (Winter and Spring 2007): 91-109.

[5] King, Jeanette. “Language is Life: The Worldview of Second Language Speakers of Maori.” University of Canterbury. http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/ILR/ILR-8.pdf

[6] Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples, 1996. “Gathering strength: Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services.

[7]McIvor, Onowa. “Building the Nests: Indigenous Language Revitalization in Canada Through Early Childhood Immersion Programs.” Diss. University of Victoria, 1998

[8] United Nations, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organizations. “Language Vitality and Endangerment.” http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/doc/src/00120-EN.pdf