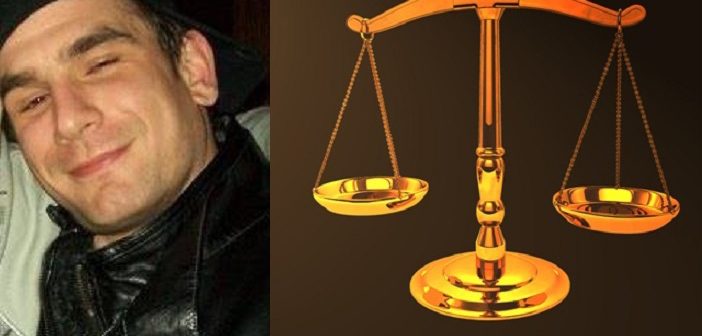

In making his reasons public for accepting the plea bargain that saw the first-degree murder charges against Ron Mitchell, Eric Mearow and Dylan Jocko reduced to manslaughter in the vicious slaying and dismembering of Wesley Hallam, Superior Court Justice Ian McMillan made some cogent arguments.

Under the deal the three would plead guilty to charges of manslaughter and offering an indignity to a dead body. Sentences were to be 10 years in prison on the manslaughter charge and three years to be served concurrently on the charge resulting from their cutting off of the head, hands and feet of Hallam after they killed him.

Under ordinary circumstances in regard to an ordinary case, I probably would have accepted McMillan’s reasons without comment.

Not in this one.

McMillan said in his explanation that although the court is not bound to accept the sentence component of a joint submission and retains its discretion to reject it, a plea bargain is to be given serious consideration

He said the value of resolution discussions was characterized in a judicial report as being “inherently desirable” and expressed that a court ought only to depart from a joint submission where not to do so would bring the administration of justice into disrepute or would otherwise be contrary to the public interest.

It seems he didn’t think this plea deal had such components as bringing the administration of justice into disrepute or being contrary to the public interest.

But I would suggest that if he had any feel at all for the pulse of this community, he might have thought otherwise.

Already frustrated by the light sentences handed down in the Jeff Holmes case, which involved the theft of $600,000 over seven years from Algoma Public Health, and in the Cynthia Jacobs case, which involved the theft of $390,000 over six years from the University of Algoma, residents of this city are outraged over this one.

I will admit that this case has caught the public eye more than usual because of the horrifics of it, the cutting off of the victim’s head, hands and feet after the killing.

But it still remains that Hallam, whom it is agreed was the first to pull a knife, was unarmed when he went down under attack by the three, Mitchell administering the fatal stab wound to the neck.

That is murder, not manslaughter, in my mind.

In any event, rather than being orchestrated through a backroom deal from which two of the major players, the Sault Police Service and the OPP, were excluded, it should have been left to a jury to decide guilt or innocence, with the penalty flowing from that, 25 years if the conviction was for first-degree and a minimum of 10 years if it was for second degree.

McMillan said although the jointly proposed sentences were not binding on the presiding judge, by reason of the pleas of guilty having been secured pursuant to the resolution agreement struck between the Crown and defence counsel, the sentencing judge is somewhat constrained pursuant to the jurisprudence that has evolved on the issue

“Arguably, the offence of manslaughter carries the broadest range of discretion in sentencing. as it may involve circumstances that are marginally beyond inadvertence at one end of the spectrum and those approaching murder at the other end,” McMillan said. “There exists a plethora of jurisprudence concerning manslaughter cases that demonstrate the very broad range of penalty and the endless variety of circumstances leading to the victim’s death.”

He said the offence of manslaughter in this case bears a maximum sentence of imprisonment for life Pursuant to Sec. 236(b) of the Criminal Code and the offence of indecently interfering with human remains provides for imprisonment for a maximum term of five years.

McMillan said the sentence proposed in the joint submission by the Crown and defence was not unfit or demonstrably unfit.

In his mind.

I dare say the public would have been more satisfied with sentences in the maximum ranges he mentioned.

McMillan outlined aggravating factors as: The assault was three on one; all accused have criminal records; the fatal wound was caused by a knife; efforts were taken to conceal body parts; fleeing the scene and the city in efforts to avoid detection; the brutality and violence of the dismemberment; and the fatal stabbing was administered after the victim had been disarmed.

He listed mitigating factors as: Guilty pleas albeit late in the proceedings avoided a lengthy jury trial; the victim initiated the altercation and was first to draw a knife; significant intoxication; expressed remorse by Mitchell; and agreed statement of facts resolved acknowledged frailties in the evidence and the specific roles of the offenders.

In regard to acknowledged frailties in the evidence, Assistant Crown Attorney Philip Zylberberg of Sudbury had told the court:

“Yes, your honour, I can indicate that in agreeing to accept the plea of guilt to manslaughter, with a joint submission on sentence, rather than proceeding to trial for murder, the Crown has taken into consideration that there are potential frailties in its evidence and triable issues as to whether the accused persons had the necessary mental element needed for murder, considering, among other factors, provocation and their level of intoxication.

“In those circumstances, and after broad consultation with the Criminal Law Division, we have decided that it is appropriate to proceed as we are proceeding today.”

I don’t buy the argument of frailties in the case nor, it has become obvious, do the police, Sault chief Robert Keetch asking for a third-party review of how this plea deal came about.

The only frailties that seem to be obvious was that the three accused had been heavy into both drugs and alcohol. But that is a high bar to hurdle in a murder case and the fact remains that they were cognizant enough to cut up the body and attempt to dispose of it. To me, that says with a high degree of certainty that they weren’t totally out of it.

But now that it is all over, I think what most of us want to know is how this case seemed to be taken out of the hands of the Sault Crown attorney’s office.

Our Chief Crown Attorney, Kelly Weeks, was seemingly assigned the second seat behind Zylberberg, an assistant Crown from Sudbury who, McMillan noted in his reasons report, presented the Crown’s case throughout.

Weeks had been involved in the case from the onset of the investigation, through preliminary inquiry and pre-trial arguments and, from what I have been told, had a very good relationship with investigators.

So with an assistant Crown from Sudbury assuming such a prominent role, it is hard to escape the thought that the majority of the decisions were made by John Luczak, director of Crown Operations, North Region, in Sudbury.

There is no doubt, as McMillan said, the decision to proceed on charges of manslaughter as opposed to the previous murder charges lie entirely within the Crown Attorney’s prosecutorial discretion.

And there is no doubt that it was within his discretion to accept the plea deal.

But that is to look at the decisions only from the legal side of things.

Looking at them from the moral side, which is to say from the community’s side and the Hallam family’s side, a far different picture emerges.

In it, these guys got a pass.

Doug Millroy can be reached at millroy@gmail.ca.

1 Comment

Great editorial Doug and comments.

The bottom line as echoed by everyone I have discussed this issue with, and as you have pointed out, is why the Crown would not have simply let a jury decide.

I am certain that the Hallam family would have agreed to take their chances with a jury trial.

Is the Crown trying to make the general public believe that there was a chance that a jury would have acquitted these three? I find it very hard to believe that.

I hope there are at least some answers coming from Sault chief Robert Keetch asking for a third-party review.