“The very first thing people need to know is that Gladue isn’t a ‘get out of jail free’ card. Gladue reports are about restorative justice and healing.” ~ Mary Bird, Nishnawbe Aski Legal Services

*****

On March 12th, 2015 Legal Aid Ontario announced provision of funding in the amount of $467,376 to Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto (ALST) for the hiring of four Gladue writers in Sault Ste. Marie, Sudbury, North Bay and Windsor.

ALST is the acknowledged best practice leader and provider of Gladue services and were the first organization to provide Gladue reports to the Courts beginning in the fall of 2001.

“Gladue workers are very needed in the Algoma District,” commented Linda Beam-Senecal, Native Liaison Worker with the Algoma Remand and Treatment Centre. “I’m very happy that Aboriginal Legal Services have received that funding and are able to provided services. They are the leaders in Gladue report writing.”

Statistics provided through the Office of the Correctional Investigator show that in 2013 Aboriginal people made up about 4% of the Canadian population, as of February 2013, 23.2% of the federal inmate population is Aboriginal (First Nation, Métis or Inuit). There are approximately 3,400 Aboriginal offenders in federal penitentiaries, approximately 71% are First Nation, 24% Métis and 5% Inuit.

Information provided by Ministry of Correctional Safety and Correctional Services indicates that for the 2013/2014 year, there were 786 total admissions to the Algoma Remand and Treatment Centre. Of those admitted 212, or 27%, self-identified as Aboriginal.

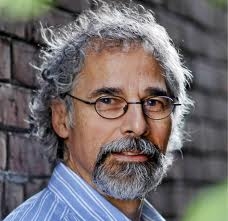

Johnathan Rudin, LLM, is the Program Director with ALST. His roots with the organization run deep having been hired to establish the entity in 1990. In 1999, Mr. Rudin appeared before the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Gladue and represented ALST before the Supreme Court in R. v. Ipeelee in 2012. His extensive curriculum vitae includes assisting with the creation of the first Gladue Court in Toronto, Ontario.

Johnathan Rudin, LLM, is the Program Director with ALST. His roots with the organization run deep having been hired to establish the entity in 1990. In 1999, Mr. Rudin appeared before the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Gladue and represented ALST before the Supreme Court in R. v. Ipeelee in 2012. His extensive curriculum vitae includes assisting with the creation of the first Gladue Court in Toronto, Ontario.

In an interview with the Northern Hoot, Rudin remarked of the expansion of Gladue services, “We certainly have known that there is a need for this service in the North for a long time. We have been advocating for this service to be provided and we’re very happy that it has finally come to pass.”

Gladue rights refer to the special considerations set out by the Supreme Court of Canada that must be applied to all Aboriginal individuals- status or non-status Indians, First Nations, Métis, or Inuit and regardless of whether or not the individual lives on or off reserve or in an Aboriginal community.

“It is important to know that Gladue reports aren’t done as a favour to Aboriginal people,” explained Rudin. “First of all the need for this sort of information comes from the Criminal Code of Canada.”

Section 718.2 (e) of the Criminal Code of Canada states in part, “A court that imposes a sentence shall also take into consideration the following principles: all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of aboriginal offenders.”

“The requirement is not for the Gladue reports,” continued Rudin. “Rather it is that people have to provide information to the Courts and we have found that Gladue reports are a very good way of providing that information.”

In 1995 Jamie Gladue was a young Aboriginal woman with one child and a second on the way. Gladue’s fiancé was known to have had several affairs during their relationship, including an affair with Gladue’s sister. It was at Gladue’s birthday party that she observed her fiancé and sister leave the gathering together. After consuming an excessive amount of alcohol Gladue confronted her fiancé back at their home and stabbed him to death. Gladue was eventually charged with manslaughter and sentenced to three years in prison. Gladue appeal of the sentence was dismissed before the British Columbia Court of Appeal.

In 1999, believing that the Court of Appeal had not acknowledged her Aboriginal status, Gladue’s case was brought before the Supreme Court of Canada who agreed that the Court of Appeal failed to acknowledge her status but also agreed that the sentencing was fair.

Jamie Gladue’s case was the first to challenge section 718.2 (e) of the Criminal Code.

The significance of Gladue’s case was the resulting message issued by the Supreme Court that Aboriginals in Canada and in the justice system experience racism and as evidenced in the penal system, are over-represented. These factors, according to the Supreme Court of Canada, emphasized subsection (e) of section 718.2 that special consideration must be given to Aboriginal people in the Courts to ensure fair treatment.

“The Supreme Court told us what we knew- that the over-representation of Aboriginals is a crisis in the Canadian criminal justice system,” remarked Rudin. “Judges also told us that to address this they need two things- they need information about the individual and their individual circumstances as well as their background and systemic factors. And secondly, in light of that information, they need recommendations that would make sense for the individual as an alternative to incarceration.”

In 2001, Rudin, in his role with ALST, established the first Gladue Court in Toronto. “When the Court was set up we thought that it would be necessary and a good idea to have someone that could write reports and we came up with the name ‘Gladue report’.”

It is estimated some 40% of Aboriginal inmates in prisons today are residential school survivors. Many others are intergenerational survivors, and /or have survived the child welfare system, including the 60’s scoop, and other legislated legacies of colonization. ~ Native Women’s Association of Canada

So why the need of ‘special consideration’ for Aboriginal people before the Courts?

Centuries of systemic abuse beginning with the height of colonization in the early 17th century and extending hundreds of years later to the closure of the last residential school in Canada just eighteen years ago in 1996, have left a dark stain upon the legacy passed from one generation to the next. These atrocities, short of the near genocide of the First Nations, have left a people struggling to reclaim their cultural identity and spirituality, recover lost ancestral tongues and restore family unity that was defiled by the intervention of the government and church between parents and their children.

Centuries of systemic abuse beginning with the height of colonization in the early 17th century and extending hundreds of years later to the closure of the last residential school in Canada just eighteen years ago in 1996, have left a dark stain upon the legacy passed from one generation to the next. These atrocities, short of the near genocide of the First Nations, have left a people struggling to reclaim their cultural identity and spirituality, recover lost ancestral tongues and restore family unity that was defiled by the intervention of the government and church between parents and their children.

And what were the long-term consequences of the governments organized attempt to wipe out the First Nation culture? Among them, lower rates of education and income and increased rates of addiction, homelessness, abuse and incarceration.

“The Supreme Court, as well as many other people, have said that there is a history of colonialism and specific government practices that have targeted Aboriginal people that have had a particular impact on Aboriginal people and are certainly one of the root causes as to why Aboriginal people find themselves before the Court,” expounded Rudin.

“The other important point to note is that many people find themselves before the Court. What is of particular concern is that Aboriginal people in the Courts often find themselves getting a jail sentence. Not everybody that is found guilty goes to jail but Aboriginal people tend to be disproportionally over-represented among those who do go to jail.”

According to a 2013 report issued through the Office of the Correctional Investigator:

- In 2010-11, Canada’s overall incarceration rate was 140 per 100,000 adults. The incarceration rate for Aboriginal adults in Canada is estimated to be 10 times higher than the incarceration rate of non-Aboriginal adults.

- Since 2000-01, the federal Aboriginal inmate population has increased by 56.2%. Their overall representation rate in the inmate population has increased from 17.0% in 2000-01 to 23.2% today.

- Since 2005-06, there has been a 43.5% increase in the federal Aboriginal inmate population, compared to a 9.6% increase in non-Aboriginal inmates.

“We’re incarcerating Aboriginals at astounding rates,” remarked Mary Bird, lawyer and manager at Nishnawbe Aski Legal Services in Thunder Bay. NASL provides service to all members of Treaty 9- an area that runs along the Quebec border, along the James Bay coast, down to the Manitoba border and then back across Haida land.

According to Bird, statistics gathered during March 2011 regarding the percentage of incarcerated Aboriginals at the Kenora jail indicate that 93% of the inmate population are Aboriginal. However, the jail services the Kenora district which encapsulates about thirty First Nation communities.

“If we look at the northeastern region of Ontario as a whole the incarceration number of Aboriginal people is close to 80%,” stated Bird with a degree of exasperation in her voice. “That number makes no sense. To accept that it does, would be to accept that Aboriginal people are bad people and worse than the rest of the population. That simply isn’t true.”

It was announced in November 2014 that NASL would receive funding from Legal Aid Ontario to hire 3 Gladue workers to be located in Thunder Bay, Timmons and Sioux Lookout.

In 2012 the Gladue case was referenced before the Supreme Court once again in R. v. Ipeelee. The case involved two Aboriginal men. One defendant was Manaise Ipeelee, a 39 year old Inuk from Iqaluit, and the other defendant was Frank Ladue, a 50 year old from Ross River Dena Council in Whitehorse. Ipeelee’s alcoholism began at the age of 12 years when he lost his mother who also experienced addiction. By the age of 19 years Ipeelee had 36 convictions including one charge of a violent sexual assault. Ladue was sent to residential school when he was 5 years old and began drinking at the age of 9 years and shortly turned to hard drugs. His offences included numerous sexual assaults against women who were drunk or unconscious.

Their appearance before the Supreme Court regarded their violation of their long term supervision order (LTSO) which resulted in their resentencing. Upon reviewing the Gladue factors and the purpose of the Gladue principles, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the importance of Gladue and that its’ principles must also apply to sentencing long term offenders for breach of LTSO’s. Also, “the majority of justices in Ipeelee note that over-representation and alienation of Aboriginal people in prison has only worsened in the years following Gladue.”

“The very first thing people need to know is that Gladue isn’t a ‘get out of jail free’ card. Gladue reports are about restorative justice and healing,” asserted Bird. “Equality doesn’t mean treating people the same. You have to treat people according to the circumstances. We hear it all the time- that Gladue’s are supporting a two-tiered justice system. But that’s not true. We have a multi-tiered justice system because every individual that comes to our Courts should be treated as an individual. And that’s what Gladue principle’s reinforce.”

“The very first thing people need to know is that Gladue isn’t a ‘get out of jail free’ card. Gladue reports are about restorative justice and healing,” asserted Bird. “Equality doesn’t mean treating people the same. You have to treat people according to the circumstances. We hear it all the time- that Gladue’s are supporting a two-tiered justice system. But that’s not true. We have a multi-tiered justice system because every individual that comes to our Courts should be treated as an individual. And that’s what Gladue principle’s reinforce.”

According to John Braithwaite (2004), restorative justice is “a process where all stakeholders affected by an injustice have an opportunity to discuss how they have been affected by the injustice and to decide what should be done to repair the harm. With crime, restorative justice is about the idea that because crime hurts, justice should heal. It follows that conversations with those who have been hurt and with those who have inflicted the harm must be central to the process.”

Rudin went further to explain that a Gladue report, when conducted thoroughly, is in and of itself a component of restorative justice.

“Ideally a good Gladue report is restorative justice in the sense that what we do is try to get the individual to think about their life in a different light. Part of that process is for the person to think about what has worked for them, what their strengths and challenges are and how they might address those challenges.”

The legacy of the residential school system demoralized Aboriginal cultures and disrupted families for generations. The devastating effects of residential schools have a long reach. Those who are survivors were abusively conditioned to disassociate from their culture and the generations after have carried this stigma forward.

Rudin noted that reviving, or in some cases discovering, cultural identity is significant to the restorative justice process for Aboriginals.

“What we see often is that for most of our clients, they don’t have any sense of cultural identity. Other people may have told them who they are but that person-the offender, doesn’t know who they are. They may not even feel like an Aboriginal person because they don’t know much about their culture but that’s how everybody else views them. They’ve often experienced racism. It is a huge issue that we give a lot of attention to.”

On release, in a way that is similar to their exit from residential schools, they are sent back out more wounded, angry and institutionalized. Communities are generally ill prepared to accommodate ex-offenders. The cycle of re-offending then continues: individuals are blamed while families and communities bear the brunt of a failed system. ~ Native Women’s Association of Canada

Aftercare services for people is utmost and Rudin admitted that it is an issue that can be challenging.

“Gladue is not the end of a process but ideally the beginning of a process that others will help the individual carry through with. Often people say that the challenge in trying to make Gladue real is that there are not resources in the community – or not enough. I think that is probably true of most communities.”

However, for a community like Sault Ste. Marie, Gladue services introduced into the local social fabric can serve as an impetus for positive growth.

“We have noticed a couple of recurring themes in communities where Gladue’s are introduced,” elaborated Rudin. “One, there are resources in communities, particularly small communities, that are not necessarily professional resources. There may be Teachers or Elders in the community that we can rely on and we need to explain that to the Courts. The other thing that we’ve found is that sometimes once we start writing reports that gaps and services are identified. That allows the community to address those particular gaps.”

Of meeting the challenge of follow-up resources Rudin commented, “We hope that it will galvanize people and we’re certainly willing to help in that regard as well.”

The hiring process for Gladue workers in northeastern Ontario is underway. It is hoped that the new writers will be established and operational by the middle of May.