It is not uncommon to hear of little boys and girls, our children, to be enamored with the idea of being a police officer, shaped by the racy visions they see on screen of fast cars, blazing lights, flashing guns and badges -heroes to the rescue. Speaking with young adults considering policing as a profession, they often express a desire to help the citizenry. They’re also attracted to the excitement of the profession and the financial security. But with the explosion in the number of cell phone cameras and people eager to capture and share images of police behaviour on social media platforms, the blue curtain has been shredded, exposing old conventions in policing that haven’t evolved with the changing culture, shocking and disheartening the people they serve.

The Northern Hoot reached out to former Saultite, Constable Jon Carson, now a Training and Educational Officer with York Regional Police, and Dale Curd, Toronto based psychotherapist, to continue the dialogue about the use of force in policing, precipitated by our story about a lawsuit pursued against the OPP by a twice tased Sault business man. Right on the heels of the Forcillo verdict in the shooting death of Sammy Yatim, Constable Carson and Curd emphasize the urgent need to equip new police recruits and seasoned officers with an arsenal of de-escalation tools.

“Verbal de-escalation has been around for a long time, it just hasn’t been in the general law enforcement population,” remarked Curd. “Typically officers tasked with hostage negotiations or special investigations are the people that receive that type of training. I think what we are seeing is that it’s the patrol officer that really needs these types of skills, they are the ones that are engaging these individuals first.”

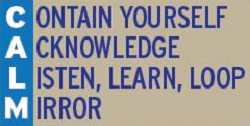

Curd and Constable Carson have developed C.A.L.M., a de-escalation technique which has been incorporated into York Regional police recruit training. The four-step method has been shared with police forces that request it. C.A.L.M. training instructs officers how to identify and engage people who present compromised cognitive functioning –irritation or agitation, triggered by myriad factors, without conflict, force or altercation. The de-escalation model is founded on best practices in mental health facilities where staff are not permitted to carry weapons, as well as Curd’s experiences over his fifteen years in practice.

Curd and Constable Carson have developed C.A.L.M., a de-escalation technique which has been incorporated into York Regional police recruit training. The four-step method has been shared with police forces that request it. C.A.L.M. training instructs officers how to identify and engage people who present compromised cognitive functioning –irritation or agitation, triggered by myriad factors, without conflict, force or altercation. The de-escalation model is founded on best practices in mental health facilities where staff are not permitted to carry weapons, as well as Curd’s experiences over his fifteen years in practice.

Curd emphasized skills reinforced through C.A.L.M. are active listening and self-monitoring. Active listening involves a style of listening that takes in visual cues like body language, making eye contact and observing increases or decreases in agitation. Self-monitoring –being aware of and keeping in check emotions, is a critical skill for officers who influence the atmosphere for the interaction. However, self-monitoring is much more than that.

Over his fifteen year career in policing, Constable Carson has seen all the ugly society offers. It nearly destroyed his life. He testifies it was the excruciating exploration of the job’s emotional effects and coming to terms with his baggage that saved his life. His trigger moment, seven years ago, started out as a ‘normal’ call that quickly took a tragic turn. A healthy baby, birthed in a toilet, left to drown by the family –it undid him. “Twelve hours later I went home to my own baby. There wasn’t any time for me to process what happened at work. I just had to bury it.”

Constable Carson used alcohol to self-medicate, was quick to anger on the job and at home, and he disengaged from his family. He convinced himself that he was burnt out from the road and just needed a change within the force. He accepted a position in the detective offices and then later a role as a school liaison officer but his internal wounds festered. His wife, also an officer, gave him a choice –his young family or the door. Constable Carson chose his family. “It was almost three years after the incident that I was finally driven to go and get some assistance. And I knew that there was going to be some deep and dark places that I’d have to go to, to get the help that I needed to get better.”

Receiving a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, Constable Carson began counselling with a therapist and disclosing his feelings to other men in organized groups. Today, Constable Carson has been invited to share his story upon many platforms, including his classroom.

“I think one of the most important things that I have done is take up meditation. It helped me immediately and it’s probably helped me the most because it has allowed me to process what I go through on a daily basis. I don’t hold on to it anymore. I let it go.”

Meditation, or as Constable Carson prefers to refer to it – ‘mindfulness’, has been shown through MRI scans to shrink the amygdala – the part of the brain associated with fear and emotion which triggers the body’s response to stress. The pre-frontal cortex – the part of the brain associated with higher order functions such as awareness, concentration and decision making, becomes thicker. The science suggests the practice of mindfulness increases an individual’s ability to draw on pre-frontal cortex functions, owing to more thoughtful responses to stress as opposed to primal reactions.

“Practicing mindfulness has made me more aware of myself and therefore more aware of others. I have a better, empathetic and compassionate approach towards people that have their own crisis going on. As it pertains to the policing world, I’m much more aware of my emotional triggers and how I react in a situation,” shared Constable Carson.

York Regional Police are breaking new ground with an unorthodox training curriculum for their new recruits. Mindfulness Based Resiliency Training, delivered by Constable Carson, in combination with the C.A.L.M. technique, are designed to rouse the recruit’s emotional I.Q. –recognizing one’s own emotions and the emotions of others to inform an appropriate response to a situation. In other words, these are tools that help the officer de-escalate their own emotions so that they can assist a person who is in crisis.

In July 2014, the York Regional Police Crisis Intervention Program was recognized by the Canadian Military with a Generals Accommodation for their efforts focusing on mental wellness and assisting military members. Constable Carson accepted the award.

“Most police officers out there want to do the job well. We, unfortunately, sometimes get lost in the emotions that take place on the job,” acknowledged Constable Carson. “Emotional I.Q., that self-awareness, is monstrous when it comes to dealing with these emotional situations that police officers are encountering. Bringing into practices mindfulness and C.A.L.M. techniques, we can listen effectively and become better at helping rather than showing up to a call and reacting. We can do a better job at that if we give every officer these tools.”

Curd believes that North America is on the cusp of transition for law enforcement practices. “I think that a variety of factors are converging to have law enforcement engage with the society that they are charged with protecting in a much different fashion than they have decades before,” remarked Curd, then adding, “And for some law enforcement agencies that’s been a harder transition than for others.”

The 2015 CBC documentary, Hold Your Fire, reports that though there is no entity in Canada officially recording the number of fatalities by police officers that “extremely conservative numbers from inquest records from 2004 to 2014 reveals 72 people in crisis were shot by police –almost 40% of all police shootings. From time to time the focus shifts on to the disproportionate number of non-white victims but always at the core seems to be the excessive use of force against people in crisis.”

In some of Canada’s larger urban centres special police units composed of officers and a mental health professional have been designed to respond to crisis calls. The reality that manpower is limited to support such specialized units underpins the urgency to provide de-escalation training to officers. The increase in use of force by police as a response to crisis calls is in part due to an increase in such calls but also owing to old doctrine that lethal force is the only defence against edged weapons –bladed or non-bladed, and sometimes even when the person in crisis isn’t holding a weapon. As reported in Hold Your Fire, an antiquated training video for police officers –Surviving Edged Weapons, establishes a 21-foot rule for managing people holding edged weapons. The 21-foot rule has become a common explanation among officers who draw their weapon –gun or taser, on an individual who is perceived as a physical threat.

Terry Coleman, Public Safety Consultant and a Member of the Order of Merit of the Police Forces, has stated of the hiring of new officers, “I’m not satisfied that police agencies routinely hire the right people. I don’t think, sometimes, they are paying enough attention to some cautions put up by psychological screening or polygraphs –integrity screening. And they quote-unquote, take a chance.”

Coleman was a consultant to the independent review, Police Encounters With People in Crisis, a critical evaluation of Toronto Police Services (TPS) undertaken by the Honourable Frank Iacobucci at the request of TPS Chief of Police, William Blair, following the death of Sammy Yatim. Yatim was fired at nine times and shot eight times to death by Constable James Forcillo and tased afterwards for good measure by Sergeant Dan Pravica,

Though the report was prepared for Toronto Police Services, Iacobucci urges the wide application of its findings and eighty-four recommendations across Canada’s police agencies. The pivotal review examines “the policies, practices and procedures of, and the services provided by, the Toronto Police Service with respect to the use of lethal force or potentially lethal force, in particular connection with encounters with persons who are or may be emotionally disturbed, mentally disturbed or cognitively impaired.”

Among Iacobucci’s recommendations are (7) that preference or significant weight be given to new police recruits who: engage in significant community service with exposure to crisis; have experience with mental health, be it direct personal experience with family members or work in a hospital, community service; and possess higher education where post-secondary education is completed or substantially equivalent education. Recommendation (11) advises TPS to instruct psychologists to screen for new constables using an assessment of positive traits while also assessing for the absence of mental illness or undesirable personality traits. Recommendations (33-40) place focus the need to develop wellness strategies, policies and procedures for police officers that are respectful of the stresses and potential to mental injury on the job. Additional recommendations throughout the report urge new practices and philosophies regarding the use of all guns and tasers.

Iacobucci’s review calls for an overhaul of policing practices in Toronto, while encouraging all police agencies across Canada to consider transferrable applications made in the report. The proliferation of indisputable videos captured by the public reinforces the vital need to spare no haste implementing recommendations.

Breaking policing tradition will no doubt require a great deal courage, as Constable Carson has discovered. “I still get a lot of flak from older officers that don’t want anything to do with me. I’ve been told I’m a salmon swimming upstream.” His convictions have not been dampered by the criticisms and he has “tremendous support from his supervisors”.

Demonstrating through his own example that policing can be mindful and compassionate, Constable Carson is realistic about the challenges ahead which will require complimentary partnerships with diverse agencies as well as support from the public. “It’s not always the responsibility of just the police officers or the politicians or the experts to make a happy, healthy community –it takes everybody to do that. When things aren’t being done right, there needs to be accountability but it will take a community to make sure that the things that need to happen are in place to help police do their jobs better. That gets lost in a lot of this.”

Curd is quick to acknowledge that mental and emotional wellbeing of police officers has often been overlooked in policy and procedure development. Curd is critical of WSIB benefits that simply fall short. “From a policy perspective we need to take a look at some of the more forward thinking companies in the private sector that understand that the success of an organization, ergo the health of their profits, are innately tied to the health of the people that are working within the organization.” Curd iterates the need of packaging comprehensive benefits for officers with increased provision for one to one counselling as well as greater support from within the organization with focus on mental and emotional health.

Moreover, Curd calls for greater understanding from the public. “As a society we need to have more empathy for the job that these people do. It is a very difficult job and it takes a lot out of them mentally and emotionally, as well as physically. And we need to break down our own barriers in terms of seeing law enforcement as being different from us. We need to start engaging them as part of us, as part of society and taking into consideration their own health issues and their own challenges. We have a stunning lack of empathy for them. And I think that’s where there needs to be some reconciliation.”

*****

Constable Carson and Dale Curd will be speaking at the 2016 C.A.P.E. Conference hosted by York Regional Police May 30th – June 3rd, 2016. Interested in learning more about C.A.L.M? Contact Dale Curd to schedule a workshop: 416.409.9700. You can also catch Dale Curd Fridays at 8:30 p.m. and Sundays at 8:00 p.m. on his CBC show “Hello Goodbye”. Keep up with Constable Carson, by checking out MindfulCop.com.