DE BIG-SHOT TRAIN: A Northern Love Affair with Algoma Central Country

A Rough and Ribald Story of a Lifetime in the Bush ~ Robert Cuerrier

Chapter 12 Chasing Critters

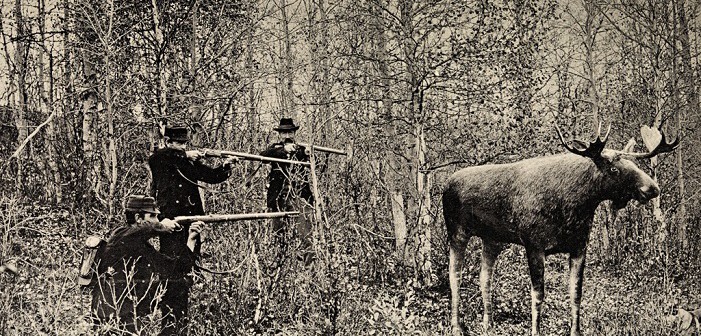

MOOSE HUNTING

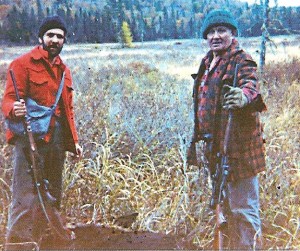

As a moose hunter I am a traditionalist. The hunt is a time of spiritual renewal and to reawaken primal urges- to hunt, to stare into campfires, feel the rain, sun, wind and snow, and to live on the land.

We hunt in lonesome areas well off the trodden path. There are no widgets with us: four wheelers, propane, chain saws, motorboats, or gas lanterns. For us it is canoes, packs, bacon, beans and coffee, bucksaws and candles.

The hunt begins by honouring the land with a purification ceremony by standing in the smoke of a cedar and birch bark fire. The belief is that the smoke rids our bodies of city scents and downtown attitudes and it prepares us to move into a brotherhood with all that surrounds.

Years ago on my first moose hunt I was reading the history of Black Elk, a Sioux medicine man. He spoke of his tobacco offering as a way to show respect to the land for an expected harvest. As I read this I figured I’d try it and crushed up a cigarette. A bull in full rut charged out at that very moment. Now I lay down homegrown tobacco leaves and feel that moose have offered themselves on every hunt so that my family might eat well.

Now my sister and hunting partner, Solange Marie Claire, believes that you should also pray savagely to St. Hubert, the patron of the hunter. She insists you’ve got to start early in the summer because by the time hunting season starts St. Hubert may be too busy to hear your call. It works for Solange.

However, you do it, the idea is to connect spiritually and to fall into the rhythms of nature and by doing so you will become at home and relaxed. You will be quieter, and your gaze becomes more intent. Slight sounds or movements will give game away. Moose can move silently and they blend into the landscape. I’ve seen patches of Labrador tea, after being stared at for hours, rise, shake and walk towards me as moose, shadows in the spruce merge into moose. They are there, you just have to prepare yourself to see and hear them.

A scout around will tell you where the moose are. Swamps with lily pads that moose like to graze on and a bit of a dry marsh to open the sight lines between the water and the bush are the best. A good place will have very evident moose trails. Some are as rutted as a cow path and as wide as an old bush road.

After you’ve found such a place, go no further. I like to build a thick bed of balsam boughs to sit and snooze on and a rough leant-to out of boughs and wide sheets of birch bark from deadfalls to keep out the weather.

Moose are curious, so when you gather stuff to build your stand simulate the Bull Moose thrashing at brush: occasionally you’ll have a visitor right away.

Moose have habits. They have a defined range and will come through time to time. You can make them come sooner by calling in the morning and evening. Don’t make more than a couple of calls each time. They can hear and may even answer. Moose have the innate ability to come exactly to the spot at which you call from even if they come from many miles away. Make the call well away from your stand. I didn’t do this once and woke up to find I almost had a Bull Moose in bed with me.

I always like to bring a packsack full of blankets to my stand. This is my vacation and sleeping is one of the best hunting methods, plus how to be quieter. I’ve gotten quite a few this way: you just tell your body to wake up when you hear them arrive. Or you can bring a kid with you who will take turns on the watch. Move as little as you can, don’t talk. Moose, although they can’t see too well, can detect motion and have ears and a nose like a radar.

Some folks don’t see right off the sport of hunting from your bed. But by sitting still you see all manner of wildlife. For a couple of years I had an owl hunting from the top of a dead tree beside my stand. We accepted each other as hunters, would check each other out, commiserated when things were slow, and on occasion he’d sweep down for a kill. Stand hunting gives you a great appreciation for undisturbed nature- game movements, subtle changes in weather, light and mood.

A good hunter will want to remove every element of sport from the shooting. The moose should be close by, unaware and turned broadside in order to dispatch it cleanly without it moving away wounded or ruining any meat. You will want to shoot where you will be able to deal with it quickly: gut it, quarter it, move it a short distance with ease, hang it, protect it from weather. You can’t do all this easily unless you predetermine where the shooting will take place.

Indians always used to move big game to them if they could. Many used inukshuks (rock structures built to resemble men) to move herds of caribou or buffalo to spots handy for butchering and transport. One plains tribe pushed buffalo out onto ice on a river that they knew would give way. The buffalo would be dragged down and swept under the ice down the river with the current.

A couple of miles away the river was open. The women would grapple the buffalo, skid them out with horses, and butcher them right there beside the camp near their tea fires.

One of the more sporting aspects of the hunt is the call, which you should practice before the hunt. Here on the farm I can do this all day and anywhere. Solange figures that the car on the way to work is a good place to work on the call but the office she has learned, is not. My call is so effective I can bring out herds. Those who know me swear that in moose season my already prominent nose seems to grow bigger as I take on the karma of the moose.

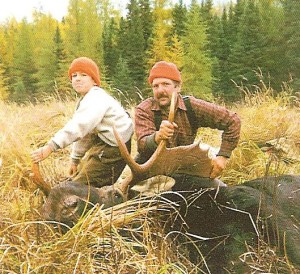

YOU’LL NEED A KID ALONG

When you’re packing the outfit for a hunting or fishing trip you shouldn’t forget to throw in a kid as a fairly handy accessory. The kid we baptize “The Pup”, “Showboy” or the “Checch”, short for cheechacko -greenhorn, novice, destined to a long apprenticeship as the “showboy”. I liked to start them young, well in advance of their best-before date. Mine were visiting the cabin as infants, day tripping as toddlers, on the deer hunt as five year olds and on deep woods moose hunts the year after. You can’t risk waiting and trying to train a teenager who knows more than you do.

I used to build up their anticipation at home with stories and practices when I put them to bed –all the great fun we’d have, what to do when you sight game, where to position yourself during the shooting, and mostly how quiet and careful you must be. Both my boys were issued axes as four-year-olds: it only took my oldest twenty minutes before he banged his ankle in his first lesson which made me wonder if he was paying attention.

But as I said, they are handy. They are all the time trying to impress you, especially on the portages. By the time a kid is a teenager he’ll want to show up the old man, and if you subtly work this to your advantage the Cheech will be a regular bundle of packs and equipment with every passage.

Kids have a good memory for detail. They know where things are when you’re pacing to go, they don’t let you forget anything and once you’re at the campsite you can send them to go for a root anytime you want an item. Or for water. Kids love to make campfires, so you let them, and along with that comes the responsibility of making wood.

When you’re on the stand you can relax with a nap knowing the kid is watching intensely. Here again I’d trained them with role playing at home- just to touch me gently at a sighting and not to say anything. If the weather gets brutally cold you don’t mind doubling up your blankets with the kid, something you’d never consider with another man. A Cheech is just as good as a big hot stone.

Further, kids love firearms and should be shown how to care for them right away. I haven’t had to clean my rifle going on forty years. As a reward I let them do the shooting as soon as they are able. My job is still the gutting; they can do it but the old man’s faster.

With the boys, I know I’m secure on the hunt in my old age and look forward to someday walking over the portages carrying nothing more than my rifle and the tea pail.

EARS OF CHRIST

Salt Pork was our food staple in the bush. It came in salted blocks, about half fat, half lean at best. It would keep all summer long without refrigeration in a brine solution. You cut it into slices about double the thickness of a thick sliced bacon, boiled it for about twenty minutes to take some of the salt out, and then fried it like bacon.

In French it was always referred to blasphemously as “les oreilles de Christ” because it curled up in the frying pan and looked like a withered ear. Put a drizzle of maple syrup on it towards the end of the frying and it is truly delicious.

We served it with a dish of fresh vegetables all boiled together- potatoes, cabbage, onions and carrots- all of which only needed a cool place to stay fresh This diet greatly simplified and economized the management of the food supplies and gave us a dinner that would hold up. The work was hard, we were always hungry and even though supper was always the same during the summer months we never seemed to tire of it.

Salt pork was the meat that fueled the Canadian pioneer era. Years ago logging contractors wanted port that was particularly fat, thinking that it would be a stronger food for men working in the cold and would be cheaper. They used to call it “long clear”. Many an old logger saw the grub getting better in the camps by the 40’s. When they first saw ham being served in camp they would say “We’ve been eatin’ that pig for years now and finally we’re through the fat and onto the lean”.

PORTAGES

My sister, Solange, didn’t care for the long portages on the way to the family moose hunting swamp especially if she had the heavy pack with the salt pork. Her suggestion always was that we walk a pig over the portages.

HEAVY FUEL

Solange was a heavy feeder – trim and athletic but a real diner when she was on the land. Leonard St. Jean Baptiste used to tease her about it often by glancing over at her plate during meals and asking “Solange, where are you logging?”

BIG PIGS

In the evening and after a salt pork supper on the hunt ol’Leonard would get a little closer to the campfire. With his pipe sitting comfortably on his whiskey dampened lower lip he would clear his throat, getting himself ready to sound knowledgeable. He was going to retell his pig story, and you knew he’d be sure to have some new twists to the pig’s tale. So you listened.

First of all he’d personalize it for us by first remind us of the old home place near the village of Moose Creek where we farmed long ago. We raised pigs, had three or four sows, all of whom we made pets of with special treats and petting. Yet you couldn’t enter that pen without a crowbar and another man present. Those big sows could chew you up if you ever went down there.

When we harvested one it’d never go to an abattoir (a “pig out-placement centre”, the old man mockingly called it in his later years). We’d do it ourselves: he’d bang it over the head to stun it and slit its throat. While the pig screeched like a soul entering purgatory, Ma Mere (grandma) would collect and stir the blood to make blood sausage all the while murmuring, “C’est bon! C’est bon!”

Leonard had an intriguing theory about pigs and their place in our history. Pigs opened the country he said –without them there would be no nation. Here’s how it went.

One sow could have up to fifteen piglets in a litter in early April. By late fall each of them would weigh three hundred pounds if well fed. That’s over two tons of meat. Compare that to a cow calving at the same time whose single offspring would weigh a couple of hundred pounds by Christmas, and you don’t have to take off a boot after you run out of fingers to do the arithmetic. “Pigs fed the pioneers,” he’d say while thumping his chest

Pigs also cleared new land. The farmer would take off the trees and make a rough fence and turn the pigs in. If you had three sows, a boar and piglets there’d be about fifty pigs working. They’d dig up and eat every weed, all the roots and shoots. Nothing was more effective before herbicide came along. They’d plough the land with their snouts; make it ready for seed and fertilize some of it. The farmer would be able to plant between the tree stumps, which he could remove later on his own time all the while having the benefit of an immediate crop.

Leonard was coming to his point. He didn’t see royals and politicians as the most wholesome folks he’d ever heard of. He couldn’t understand why they alone adorned the country’s currencies. Why the common pig had done more to open up the land. Pigs helped create the prosperity we all enjoy and were cleaner than the stained hands of most former prime ministers and certainly, in his opinion, just as cute as the reigning monarch. They should be acknowledged and featured on coins and bills. We should honour the founders. His prejudices aside, he had a good point.

One time at the end of this well-worn story he thought that he might have told too often the old man made us a promise by quietly adding, “All things have an end and a port sausage has two.”

THE MAD TRAPPER

Here’s a story of a man society near drowned in a stream of city values that drenched him and then moved casually on, uncaring, like water down the creek.

He spoke broken English, probably wasn’t any more accomplished in his native tongue, and lived the self-contained and solitary life of a trapper in the deep bush off Pan Lake. He’d built a little barn and brought in a couple of goats and a few chickens for milk, meat, eggs and companionship. I’d talked to him a few times on the train. In every way, he was all right.

Like all trappers he worked his line in the daytime and brought his catch back to the shack to thaw. In the evening he’d sit beside the guttering woodstove and skin, scrape and stretch the hides onto drying boards. When he finished with an animal he’d swing the carcass by the leg and toss it through the open cabin door towards a burgeoning heap in the snow. He likely shouted “hurrah” with each throw. This was common practice on northern traplines. The piles were a resource. Traps for wolves and foxes would be set around them and chunks retrieved to bait traps along the lines.

He looked on with pride at his front yard landscaping. It was an indicator of how well the season was going and to a trapper it was a fine sight. The snow soon dusted the heaps so they didn’t look too raw and he knew that with the melt, predators would use everything. Nature is self-cleansing, Christian burials unnecessary.

Each year during spring breakup it was his custom to go south to Muskoka to trap muskrats for a few weeks. He’d set out grain for the chickens, hay and fresh cut cedar boughs for the goats. A friend would snowmobile in every couple of days to check on his outfit and do any needed chores. He was responsible.

The year of the troubles his friend found it impossible to travel in at his regular interval but wasn’t too concerned because he cared for critters with weather contingencies in mind.

But he wasn’t the first man on site when the weather opened up. A couple of downtown adventurers happened by and, as fate would have it, found a goat had hung itself on a ladder and nobody home. They reported it to the authorities. The OPP and the Humane Society were called in to investigate, and perception soon became reality.

The media got hold of the story and pretty soon TV cameramen, newspaper photographers, writers, animal rights activists, curious sightseers and the purely self-righteous joined the congress of crows already cawing, circling and diving at the macabre sight that the melt had exposed –the yard full of carcasses and the hung goat. It looked bad,

Blazing headlines and lead stories followed. This one had all the elements. Set in the frozen north- a Mad Trapper, colourful photo ops too. The southern media jumped on the bandwagon: bushed woodsman, brutalized by a lifetime of killing, ghoulish, a real son-of-a-bitch from his socks to his toque.

A splash dam of media outrage and indignation let go and public opinion swept along with it. A conviction followed. It had been vigilante ambush, hysteria-driven with a special interest anti-trapping spin that had a popular appeal. His crime had been his lifestyle. He left the courtroom, a plaid bush shirt surrounded by starchy white collars, looking like he’d been run over by the train.

If he’s still alive, what does he think today? I think I know. He’d first of all wonder bitterly about the judgment of a society that largely turns a blind side to the homeless dying of exposure on park benches and on streets of our cities while convicting an innocent for supposed neglect: a man in perfect communion with the animals he lived with and trapped. And I can just see him sitting in his camp in the evenings, wistfully wishing all trapping would be outlawed for a few years until the roads and highways were flooded through the industry of the beaver. Then all his detractors would have to travel by canoe until they developed a reasonable appreciation of conservation and wildlife management.

WISDOM

“Don’t be too quick to judge. What the other guy does could be as innocent as a dog puking up a poisoned rat.” ~ Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

FISHING

I never had too much luck, time, or patience for fishing so never became a good fisherman. Even when I lived in the bush it seemed that I always had better things to do. I’d only fish for fun if that was the only intent and if the fish were so hungry that even I could catch all I needed.

The rest of the time I would take shortcuts. There always seemed to be an old trapper who would tell me where to set a nightline on top of a good hole. He’d understand that we were busy building and didn’t have the time to run around with a rod and a single hook. The number of hooks set on the nightline depended on how they were biting and the size of the camp being fed.

We did eat a lot of fish (fried, baked, stewed, broiled) and rice as a steady diet for a couple of weeks one time when we weren’t flush. I’ve got a fish-eating hangover that lingers to this day.

Contracting out for fish I’ve found works well. If my brother was on a fishing trip with us he’d get right at it while I set the tent up and put up a woodpile. On those trips I was showing my young son how to get by in the bush, so we brought only skeleton rations along thinking that a hungry fisherman fishes best. If we were well provisioned there’d be the seduction of the comfort of the cookfire and the tea pail. The kid hated fish: they made him sick and he puked all over us one night in the tent to prove it. He worked hard, knowing that if he took in a good catch he could eat all the Kraft Dinner. With the two of them along fishing trips were fun.

Sometimes on a hungry day when the fish were not hitting we’d just backslide to the old and tested way of the nightline.

CANOE TRIPS

You know, I don’t get the canoe trip. I think most folks are missing the point. They race through the wilderness covering a lot of ground and experiencing very little. What do you see walking portages with a canoe over your head or all humped over under a packsack, moving fast to reach your day’s travel goal only to set up a hurried little hovel before nightfall? And if the route is used at all, you’re usually camped in the middle of a public toilet area.

The immediate bush has likely been scoured and denuded of firewood. Game has been scared away. There’s bound to be company come through. Why take the bush and bring with you all the frenetic angst of the morning commute that you’re taking a break from?

Try rethinking it. Often by studying your maps you can locate idyllic little lakes or ponds just off the canoe route easy enough to reach while having some small deterrence that might discourage others. Find one from which you can day trip easily to other places you think you might like to explore.

Now you can enjoy where you are or travel lightly through the day if you wish and return to an established camp. You’ll be better prepared against bad weather with a woodpile and a tent set up to buffet storms. There’ll be a balance between high energy and quiet enjoyment. You’ll have time if you want to –to try smoking a few fish, pick berries, make bannock and explore. You’ll see more wildlife and drift into the beauty and serenity of the deep bush.

CAMP HARMONY

“Be helpful to the other guy and the rest of the time tend to your own trap line.” ~ Leonard St. Jean Baptiste

BEAR FACTS

A camp in the bush quickly becomes a refuge for strange odors. There’s people, food and cooking smells, game hung, campfires and latrines. Stay in the same place for a while and for sure flies and bears wills soon get interested.

Some people deal with bears with an excess of bravado. Naïve tourists and even some real dumb bush folks will try to touch them or even hand feed them. Leonard St. Jean Baptiste once jumped between a marauding bear and our food pack while on a moose hunt and started blazing away, proving only that he was even more serious about lunch than the bruin.

My son, Ti’Guy, when he was little used to bounce over the beds in our cabin near impaling us with a big stick, his bear spanker he called it. He hurled threats and called upon the higher spirits to bring one to him for retribution.

One day he saw a bear, dropped the stick, ran indoors into his bed and spoke no more of them.

Shoney and I cohabited with one when we were building a log camp. The bear must have been well-fed because at first he wasn’t going after our cooler, which was just a deep hole, dug into the ground. He was coming in close though and you’d come face to face with him in the middle of the night when going out to pee. He’d take off when you yelled or banged a couple of pots. I often thought what might happen if he took a paw swipe through the side of the tent while we slept but was always too tired to dwell on it. At that time we didn’t have a rifle in camp, so there wasn’t much we could do.

Later on when the cabin had a roof we moved in. There were no windows, doors or chinking but it was more commodious than the tent and drier too. The bear stayed with us and each morning would scratch the walls of the camp as our living alarm clock. We roused ourselves and smartly, always ready to hop out of any opening should he find his way in.

The bear became a nuisance and started raiding our grub. Bears, I learned, can unwrap a pound of butter and lick it clean without perforating the tinfoil or can burrow into a loaf of bread at one end, eat the contents, all without wrecking the bag. It’s hard to believe that paws that can power through the walls of a frame building could be as delicate as a surgeon’s fingers.

The bear was getting more quarrelsome and one day in a cold rain I found he’d shredded my rainwear and that was it. By this time we’d brought up a rifle and I shot him at close range: he rolled over and cannonballed away wounded. Good thing it wasn’t my way since I could never have readied to shoot again.

The shooting, because it was off-season, simulated Mr. Graham, a puffy dandy, who had recently bought the failing old lodge at the end of the lake. He boated over, affected, wearing full camo, a hireling bearing his rifle, “dismounted”, and walked over to our campfire accumulating more authority with each step. He wanted an accounting. I told him the story, and he wanted to know why I hadn’t gone looking for the bear because it might come back for revenge. As if! I told him there wasn’t a good blood track, the bear was going to die soon and more importantly I didn’t care where. Off he went, with his man, after the wounded bear.

Meanwhile, Rochefort and Giroux, two old bucherons, heard the shot and came over with a couple of shovels to help dig a hole. They’d guessed what had happened and figured I’d want a hand with the burial. We made tea, and they mocked poor Graham mercilessly with time worn insults. “He couldn’t track an elephant with a nosebleed through two feet of snow” and “There goes a man with bugger all to do and an Indian to help him”. A pale Mr. Graham returned; he hadn’t been gone too long or too far.

Then there was Shoney and the bear. We had set up a temporary privy back of the camp. Just a couple of poles between two trees, a splashboard and a shallow hole scooped out. Well he was up there one day, and just sat down and began to amalgamate his thoughts when he got a surprise. There was the big black bear laying in the hole getting interested in what was happening above him. Shoney came down that trail like the Devil skinning out from a Holy Water splash- tumbling, somersaulting, all caught up in trying to pull up his pants. I wonder if that bear was as amused as I was.

REPRIVE AND THEN A PARDON

I’d baptized him Harvey and I was going to kill him. I named him after a pilfering, a sneak-about, rat faced, slum minded yegg who’d once ripped me off. Harvey was a groundhog who was raiding our camp. Like his namesake he was a sub terrain traveler, burrowed around and popped his head up place-to-place looking for something that wasn’t his to run off with. He liked to hang out around our cooler, which was just a deep hole in the ground and where he was sure to find eggs and salted port. Harvey was the likely result of a careless upbringing.

And so I was after him and going to get him. If I had a sighting while working on the cabin I’d fling whatever tool was in my hand – an axe, framing square, cant hook, chisel or hammer. If I were at the cookfire it’d be a knife, fry pan or a chunk of cordwood.

Harvey was fast, nimble, sure of himself. He didn’t run when I spotted him but squared himself up and conceded the first move to me. I’d line him up, hurl my weapon, and he’d side step it like it was of no consequence. Like a good ice hockey goaltender there was nothing visually spectacular in his game, just deft professionalism. Even when the chase was on he could duck into one of his holes and seemingly pull it over him. He was teasing me.

Harvey was getting to me and began to take on larger symbolic meanings. I started to project on him. If I misplaced my carpenter’s pencil, well Harvey must have walked away with it; no toilet paper in the latrine, Harvey; hard words with my brother (the groundhog was stressing us out, rain on the work), must have been because I’d just seen Harvey, the harbinger of all things bad. The Watergate break in at that time, burrowers just like Harvey. He was starting to interpret my world.

I caught up with him in the cooler where I was going for a root. There he was…at the bottom of the hole and no escape. Jubiliation! I picked up the shovel that was there and got ready to practice deadly force. Harvey backed up and we caught each other’s eyes. I saw fear, desperation and resignation and could sense he knew what was coming. Just as quick it turned into bravery, like the cat backed into a corner and is no longer scared of the dog.

Well there was no way I could do it to a sport like Harvey and so declared a truce and granted him a pardon. He’d been here first and there we were cuttin’ up the trees and putting a cabin right there on old Harvey’s homestead.

I would have started feeding him, tried to make him a pet, maybe have him sit around the fire with us at night but he was a little shy after his fright and we never got that close. He steered clear of the cooler though, he knew that was not a good place and still he invited me to play although by this time it was just a friendly game.

DEEP THINKING

“There was a woman who married moose droppings but he had a Medicine Pipe between his legs” ~ Translation of a traditional Ojibway women’s song

A SKUNK ON THE MOOSE MEAT

A quick gust of irritation crossed the face of Leonard Saint Jean Baptiste as he glared out of the door of his Sand Lake shack. He started to pace like a man waiting desperately beside an occupied outhouse- really doing the hokey-pokey.

We’d just come up the river the day before with a moose. The moose had been cut up to travel, packed in burlap grain sacks in eight equal parts for easy movement by canoe and portage. Now you can keep meat almost indefinitely in the fall if it’s hung up in quarters, in the air, kept dry and out of the sun. The meat will form a hardened protective crust and pepper on the open cuts will keep the blowflies off. But in this condition it was what we called a “red hot moose”, one that had to see a butcher as soon as possible.

We had it stacked like cordwood just outside the cabin door, just waiting to be moved up to the track and then onto the downtown train. But there was a skunk on the meat pile. We were paralyzed, couldn’t do much for fear of spooking the skunk and there wasn’t another train for six days if we didn’t catch the one today. The skunk was having a lingering lunch and time was running out. Much of the meat would be lost in delay.

Leonard wouldn’t leave it alone. It bothered him because having been a farmer you wasted nothing especially food that you worked so hard to produce. He wouldn’t leave the skunk alone either. He was talking loudly, going to the door, louder now, trying to move the skunk off. He was weighing the risks here.

In a rage, he spit his chew out the door at the skunk, got a little jump out of him so he reached for his plug to reload. He pulled out his clasp knife to cut off another chaw, a big one this time, and then licked both sides of the blades clean as old men do. He was really working on it, moving that big wad anxiously from one side of his moth to another, getting ready to fire again. So lathered up he was ready for a shave.

Earl and I reheated the coffee and sat down on the stumps that passed as chairs. We were starting to enjoy this; it was getting funny. We couldn’t talk to the old man in this mood, so in perverse amusement we put on our own little dialogue to try to get through to him. We speculated about just how much of that moose we’d be able to eat in the next week, whether we could re-hang it, smoke it maybe- all in very serious voices. We had to take his mind off the skunk and onto reason before both of them blew.

The skunk didn’t move until it was satisfied. It looked like it ate a couple of pounds which was a lot considering its body weight but it was all in one neat little hole that we could easily trim out.

We made the train and the three of us laughed for years over Leonard’s vaudeville act while we waited out the skunk on the moose.

UNCLE ALBERT TAMES THE SKUNKS

There were five or six skunks in the grain shed ripping it up. They’d been there for three days and I was beside myself. Every sack had been torn open, and it looked like it all would soon go to ruin. I sure didn’t want to shoot them or risk traps. It was déjà vu all over again. Albert chanced to visit and I outlined my lament. Albert’s an unruffled problem solver and you knew he’d have a theory if not an answer. He said that it would be easy and asked if there was any over cleaner under the sink.

We went out and opened the door of the shed and Albert waited till he had their attention. The skunks all lined up in a semi-circle to look at their master, just like Sunday school kids. He sternly lectured them and then gave each one a little burst of Easy Off- a communion, on the ends of their noses. Albert’s a Highland Scot and the ceremony reminded me of a Presbyterian service and sermon on a hard life’s lesson. We quietly shut the door and left. Of course the skunk’s noses blistered up and they never came back.

Today I use the same method for skunks eating my sweet corn. I set out the live trap, catch them, spray their noses, release them and never see them again.

A SPUNKY WOMAN

My brother Earl built an authentic birch bark wigwam for us on the farm. Susie and I would visit it on our evening walk. I always insisted that we follow traditional Ojibway customs at the wigwam. The women would sit just to the left of the opening; the better to go in and out to get wood, water, gather herbs and berries and attend camp chores. The warrior, me, would sit on the far side of the fire to work on tools, make medicine and face the entrance in case of trouble. This was the man’s seat. I’d be ragging her a little bit.

The fire pit had a little underground tunnel built out of stone to bring air to it from the outside. One night with no fire, a skunk –trouble, walked in through that hole and stopped right in front of me, which shut me up. Without a word, Susie stepped through the door and went straight home. I knew she’d been readin’ too many books again and wasn’t putting up with any hint of attitude. It was lonesome waiting out that skunk.

A PRICKLY SITUATION

I was down the road visiting Silas, my old bush partner, having a campfire, and washing down all the nostalgia we were dredging up with a few beers. I had to call a cab to get back to the farm. Before going inside, I stepped behind the woodpile to get rid of some of that beer. I was swaying there somewhat, still reminiscing ‘bout the old days, when I heard a little shuffle, which turned out to be a porcupine sitting on a stump. I was almost touching it while peeing on it. Had there been contact, I’ve often wondered how I would have explained it down at the hospital emergency or whether I would have simply taken a little pair of pliers and dealt with it myself.