“Remember this: After Hitler fell, and the horrors of the slave camps were exposed, many Germans excused themselves because they said they did not know what went on behind those walls: no one had told them. Well, you have been told about Orillia.” ~ Pierre Berton, Toronto Star, 1960

“Don’t lie on your stomach when you go to sleep at night. And don’t go to sleep right away.”

The advice was administered by a guy who had been around long enough to know the ropes. It was Leo’s first night locked down with about 40 other males. For whatever reason -maybe it was the pity evoked on account of the rookie’s diminutive stature or some kindness in the seasoned internee’s heart, he was compelled to look out for Leo.

Leo was overwhelmed. Just a day ago he was packed up, stuffed into a Ford Coupe and then driven to the Algoma Central Train Station where he was loaded onto a steam engine destined for Orillia, Ontario.

“And listen, when you see the staff beating the crap out of another guy -don’t look. Just ditch. Fast.”

Leo looked down the length of the ward. There were two rows of beds running along either side of the narrow hallway. The beds were separated with barely enough room in between to squeeze in a tight fart. You’d have to crawl up the mattress from the foot of the bed to reach your pillow –if you had one.

It was a lot to take in. Especially for Leo, who was just 10 years old.

*****

At the top of the 19th century Ontario jails were convenient places to warehouse a slurry of folks- the criminal, the poor, the mentally ill, the learning disabled and the developmentally disabled. Jails were crowded and the conditions were horrendous. After visiting one jail in 1839, William Lyon Mackenzie declared the treatment of three women deemed ‘lunatics’, locked in cribs as “severe beyond that of the most hardened criminals”, concerned citizens took up a dedicated fight to lobby the government for change.[1] As a result, the provincial government passed “An Act to Authorise the Erection of an Asylum within this Province for the Reception of Insane and Lunatic Persons.” [2]

In 1876 Ontario opened its first institution for people with a developmental disability on the outskirts of Orillia. In 1876, it was named Orillia Asylum for Idiots. Later it was called the Ontario Hospital School of Orillia. At the time of its closure in 2009, the facility was known as the Huronia Regional Centre.[3]

It was 1948 when Leo walked through the entrance of the Ontario Hospital School. It was the beginning of what would be nearly 25 brutal years of institutionalization.

*****

Leo was born in Blind River, Ontario. He was one of half a dozen kids raised by a loving and hard-working single mother. Originally from the Wikwemikong First Nation Community on Manitoulin Island, Leo’s mom eventually ended up in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario working the night-shift at the Algoma Steel Plant piling the brick ovens –a man’s job back then, to put chicken on the table for her young ones. One day the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) showed up and took her children away.

Leo was eight years old and placed with his siblings in an orphanage in the Sault. His mom was unsuccessful in her attempts to recover her babies. The children remained there together for about three years until a CAS worker gathered up Leo and his meager belongings, boarded him on a train and headed for the Ontario Hospital School. CAS perceived Leo to have a developmental disability. Leo’s family was never notified of CAS’s decision to place him in an institution. It was his sister, Jenny, older by just one year, who noticed he was no longer at the orphanage.

“Where’s Leo? Where’s my little brother?” Jenny asked. “He’s gone,” they told her. But nobody would tell the young girl where Leo had been taken.

It has been noted among people who know Leo well that he has an impressive memory. Now 76 years old, Leo remembers with uncomfortable clarity the day, 66 years ago, that CAS put him on the train to Orillia.

“They just took me away. That’s when they still had the steam engines and people was still driving Model-T cars in those days. It was still back in the olden days when they took me away,” he shared.

The entrance to the main building on the empty grounds of Huronia Regional Centre. When Leo was admitted here the facility was referred to as the Ontario Hospital School. Image supplied by Jim Dolmage.

We are sitting at the kitchen table in his tiny apartment in downtown Sault Ste. Marie. It’s a damp December evening and outside the sky is grey. Melody Hawdon is there with us. She helps out Leo with day to day tasks, like managing his medications. More so Melody and Leo have become chosen family to one another. They’ve been a significant part of each other’s lives for 13 years.

Leo continues. “I asked them ‘where are you taking me’? They said ‘ohhhh I’m taking you for a nice train ride’. But they didn’t say where about. She took me away on the train and then I seen this great big brick building and I said ‘is that a school? That big building there?’ She said ‘yes, that’s your new home. That’s why I’m taking you there’. I said ‘you call that a home? Look at all the windows in it. It must be a big home.’ She said ‘oh yeah and there’s lots of people there too’. I said ‘how long am I going to live here.’ She said ‘oh, you’ll be living here forever’.”

*****

Over 100 years ago, journalist and later a government Minister, John Kelso, advocated for the protection of children in Canada. His vision was that no child should ever live in fear, harm or violence. Under his efforts the Children’s Aid Society was established and given the legal right to remove children from families or detrimental situations. ‘Rescued’ children were often placed in foster homes or institutions.

In the nineteenth century a medical model was applied to the care of people with developmental and learning disabilities. Entering the twentieth century disabilities were viewed as a flaw that could be corrected through modification and training. Eugenics tried to control groups of people who were considered to be inferior.[4] Supporters of the eugenics movement argued that people with a developmental disability were the cause of many social problems and needed to be removed from society.[5]

When the Orillia Asylum for Idiots opened in 1876 there were 100 ‘patients’ admitted. By 1890 the population tripled with 309 residents on site. In 1902 there were 652 residents, 1945 – 2,241 residents[6], 1968 reached peak population at 2,948 residents and 1975 -1,566 residents[7]. By March 2009 there would be 0 residents when the doors to the facility, now known as Huronia Regional Centre, would close for good.

*****

“Every night you had to stand in line. I don’t know how long the hall was but it was awful long,” spoke Leo. “You had to take your clothes off and fold them up and put them on your bed. You had to wrap a towel around your waist and then you have to stand in line. I don’t know how long you had to stand there. Quite a while, I guess. Then they take you down the hall to the shower room. Then only three guys at a time would take a shower. When you come out of the shower, the staff, well that’s what I call them- they look like guards, but anyways, when you come out of the shower they check you. The say ‘put your arms up’. They check your arms and check your hands, check your ears and they say ‘bend over’ and all that. They say ‘you washed yourself that good? Look at the dirt on ya’!’ They give you a whack across your ass and send you back into the shower and say ‘get back in there and bath right’.”

Melody supplemented Leo’s comment. “They hit him a lot in the head, and one time with a cup. He remembers dripping in blood. He is deaf in his left ear. He’s been deaf for many, many years.”

“A side room. Every ward had a punishment room of some kind for the men. These were isolation rooms – no windows, no beds, no facilities. when Leo was there it was documented that men were placed in these rooms for months at a time.” ~Jim Dolmage

As Leo’s trust in Melody grew over the years he began sharing the details of his life in Huronia. The confidence developing between the Leo and Melody would become a significant factor that allowed Melody to support Leo to prepare a strong claim in a class-action lawsuit against the province of Ontario for the horrific abuses he suffered at Huronia Regional Centre.

In 2010, two brave women –Marie Slark and Patricia Seth, also former residents of Huronia, brought forward a class-action lawsuit against the Province of Ontario for a breach of its “fiduciary, statutory and common law duties to the class through the establishment, operation, and supervision of Huronia”.[8] The application for the lawsuit also alleged that the Province’s “failure to care for and protect class members resulted in loss or injury suffered by them, including psychological trauma, pain and suffering, loss of enjoyment of life, and exacerbation of existing mental disabilities”.[9] This action was certified as a class proceeding on July 30th, 2010 and the settlement action was approved by the Superior Court of Justice on December 3, 2013. Jim and Marilyn Dolmage were friends of Marie and Patricia and both served as their litigation guardians in the proceedings. Jim would eventually become a supportive resource to Leo’s claim process.

Melody began the arduous task of gathering files, documents and reports accounting Leo’s life in the institution.

“I found that he had been hospitalized at one point for thirteen days with wounds to his feet and ankles,” she said. “He got an infection and it ran through his body. He was on really strong antibiotics. Because of the stories that Leo has told me for thirteen years, I’m thinking that people used to stomp on his feet, kick his feet, kick his ankles, kick him when he was down. Beat him. Between his peers and the staff, somebody really hurt him.”

Digging further into Leo’s file Melody learned that when Leo was later placed in the Edgar Adult Occupational Centre that the deformity of his feet and toes were so noted that surgery was performed on both feet.

“His toes are all different shapes,” said Melody. “His feet were broken over and over.”

*****

Jim Dolmage met Leo at an open house on the former grounds of the Huronia Regional Centre following the settlement of the lawsuit. He has helped Leo, and many others like him, document his story for the claim about his time spent in the institution.

“Huronia was the most understaffed and underfunded institutions in North America,” Jim provided during one of our phone conversations this past winter. “You could have gone to Mississippi or Alabama and found a better staffed institution.”

Huronia supplemented their staff shortage by putting the young residents to work. Leo worked on the grounds cutting the grass in the summer and in the winter shoveling snow and coal. Leo was not outfitted with the proper protection for the harsh weather and his hands would ache throughout the winter. When he wasn’t working outside Leo was inside cleaning ‘miles’ of hallways for hours with an industrial wooden floor scrubber that left his hands full of splinters and his slight body throbbing.

“It was not uncommon that the able bodied residents ran the institution,” remarked Jim. “Residents did laundry, worked in the kitchen, teenage girls looked after the babies and younger boys fed people that lived in the medical unit.”

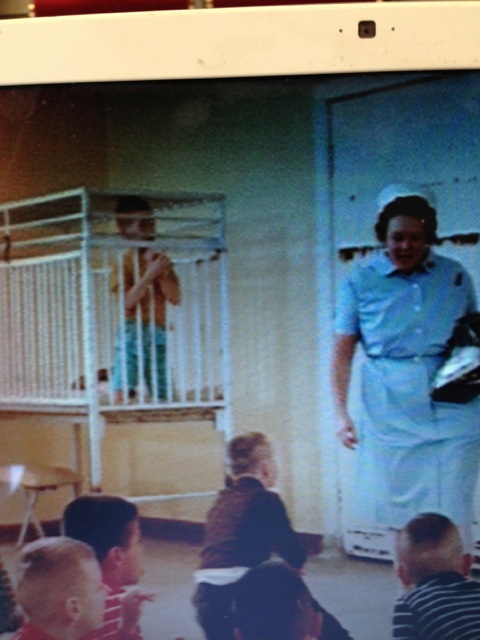

“Young children were placed in cages like this for punishment. One young boy was left in for years and his legs were all constricted as a result when he got out. The staff called him the ‘umpire’ because he couldn’t stand up. The children were numbers, nicknames or a unique Huron Regional Centre pejorative “winkie”. ~ Jim Dolmage

In addition to being understaffed, Huronia did not allow families or visitors to proceed beyond certain points of the institution. Both of these factors established the potential for all sorts of rampant psychological, physical and sexual abuse to occur. And it did.

“I had the unfortunate –in one respect, and fortunate in another, privilege to hear these same stories over and over from different people. There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that they are true and they happened,” remarked Jim.

An inspection –one of the very few, of the institution in the 70’s uncovered that among other horrors, two men had been left in segregation for over a year. Reports and stories from survivors expose murder and sexual assault in the underground tunnels that ran heat and water throughout the 200 acres of Huronia’s grounds. Cruel punishments -like ice baths, and the humiliation of residents -like forced nudity, were employed. And many staff did not stop short of their own abuse against the children.

“With the boys the staff used residents to control other residents,” detailed Jim. “There’s all kinds of stories about how the bigger boys were used to control the younger boys. How boys were encouraged to fight each other. How there were systems put into place where if a boy was out of line it was the other boys who abused that boy physically to put him back in line. There was a thing called a ‘horseshoe’ where one boy was put in the middle and all the other boys would all gather around and punch and kick him. There was another thing called ‘the tunnel’ where there were two lines of boys and one boy was forced to run down through the middle and was punched and kicked as he went through. The staff quite often physically abused the boys but even more often used the boys to abuse each other.”

Documenting the stories of sexual abuse among the male survivors was challenging. Recounting the experiences were painful and embarrassing for many. And for men in today’s society still, not something that is so easy to come forward with.

The insights Jim shared of the sexual abuse experienced by the boys may be difficult but his comments strike a raw nerve.

“I learned that the experiences of the men- it was all horrific, but the abuse to the men was even more systemic than the abuse to the women. And I put that down to the fact that the men were looked after by men. And the women were looked after by women. And the care of men for other men is simply not as sympathetic or as humane as the care of women by women.”

The sexual abuse of male residents wasn’t only perpetrated by male staff. As more male survivors of Huronia shared their stories a disturbing pattern was exposed.

“All of those men had stories to tell of a similar nature- being locked down in wards as children with other pubescent boys and being sexually assaulted by those boys. You went in there as a 9 or 10 year old and you were assaulted and then by the time you were 15 you had a string of 9 or 10 year olds that you could assault. Men have talked about this. It was just a cycle that went on and on. And that lasted right up until the institution closed in 2009.”

It is as perplexing as it is disturbing that the atrocious neglect and crimes committed against the residents of Huronia were never brought to justice in their day. Indeed, these incidents didn’t even make it into the mainstream publications of the time. The staff took oath’s of confidentiality and were threatened with job loss should they divulge the horrors happening upon the grounds of Huronia. Just as detrimental to the protection and dignity of the residents were the prevailing attitudes about people with developmental disabilities.

“To put it into perspective, when Leo was there, there was a huge siren in the facility that when anybody escaped the siren sounded and the whole community of Orillia was alerted that there was an escapee from the institution. People locked their doors, locked their windows and got out their weapons when one of ‘these people’ were on the loose,” remarked Jim.

And Leo was often cause for the siren to sound.

*****

“When I started growing up and got friends every fall we would make up a little plan. We use to run away every fall,” shared Leo.

“Well,” added Leo with a grin. “We got caught though!”

Despite the grimness of the memory Leo laughed, and so did Melody and I.

“We use to walk the railroad track up to Hawkestone there, and break into summer cottages every year. We done that every fall. Walked the railroad track. We went to the same place all the time, every year. We walked the railway track all the way to Hawkestone and break into the same cottages every year,” he said.

Leo and his friends would steal food and then find a car to hotwire. They’d drive it to anywhere until the gas tank was empty and then find another car to hotwire to stay mobile. The teenagers would keep up that drill until they were eventually caught four or five days later.

Of Leo’s interludes on the lam –moments in paradise by comparison to the institution, Jim notes that Leo’s earliest years were spent in nature. “He wasn’t someone that could psychologically adapt to institutional life. His only way of coping was to try to get out of there. And Leo has enough wherewithal –I mean, he is obviously a man with talents and he was able to keep escaping.”

Even though the punishment that awaited his return was miserable should he be caught, the chance to grab freedom was too irresistible. Eventually the youth would be apprehended and returned to Huronia. Leo and another gentleman’s story corroborated incidents of being dressed in women’s clothing.

“You had to take all your clothes off and put a pair of pajamas on or something and a housecoat. Like something like a women’s dress. I call it a housecoat. Like a kimono. We had to go upstairs and downstairs like that. We had to eat in the dining room with that housecoat on,” recalled Leo.

Leo’s partner on the run, and a person that Jim also knew well, shared with Jim memories of being called a faggot, experiencing physical abuse and being locked in a ventilator shaft for many nights while wearing ladies undergarments, after returning from the escapes.

“These are the institution made boots with winter grips. Leo would have worn them shoveling snow all winter. He also remembers staff members who kept one of the leather soles in their back pockets and hit the kids with them. Leo remembers a staff member who would say ‘come here and get a taste of sweet marie’.” ~Jim Dolmage

Leo also remembered upon his return from his brief bursts of independence, being greeted –across his knuckles, by Sweet Marie. Huronia operated a shoe manufacturing business in the basement, a sort of sheltered workshop. The soles of the winter boots were outfitted with metal crampons. Leo remembers staff who would keep a leather sole in their back pocket with which to hit the children. “Come here and get a taste of Sweet Marie,” one staff member would often invite of the residents.

“They would hit your hands until your hands turns purple,” said Leo.

Leo’s life as a serial escapee caught up with him when his ‘borrowed’ car sputtered to a stop. By that time Leo had been moved to Rideau Regional Centre for the Developmentally Disabled but he would not return to the institution. Instead Leo was shuffled into the penitentiary system spending some time in Kingston Penitentiary and then Penetanguishene Jail. He was incarcerated for three years and when he had served his time he didn’t want to leave.

“I made some good friends there,” said Leo. He asked the guards if he could stay at the jail. “They said ‘no, you done your time, now you have to go.’ They gave me all my stuff back and they opened the door and said, ‘o.k., you’re free. Get going’. I went down the steps there and I thought boy, that’s a long ways to all the way to town. I turned around and knocked on the door. The guard opened the door and said ‘what do you want’. I said ‘going to town, that’s a long ways to walk. It would be nighttime by the time I get into town’. The guard said to me ‘well, why don’t you run all the way’. I said ‘I can’t run’. I said ‘you got a car, why don’t you give me a ride’. He said ‘no, I’m not giving you a ride. You’re free to go. You served your time, now get going. I’m not giving you no ride. Walk to town’.”

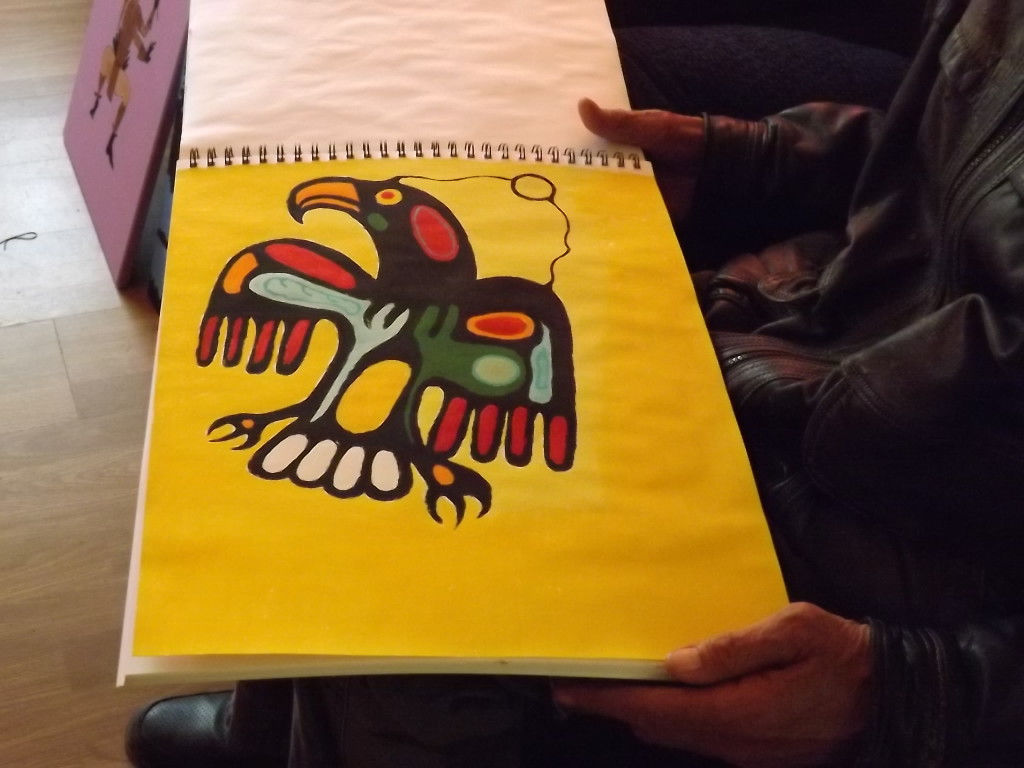

During his first stint in jail Leo’s brother and mother found him. To stave off boredom and depression his brother gave him a one hour drawing lesson. That was all that Leo needed. Leo has hosted his own art shows, sold his paintings and has been commissioned to paint and draw for many years.

After Leo was ‘kicked out’ of jail he spent some time living on the streets of Toronto and found odd jobs were he could. His childhood spent laboring in the outdoors toughened him and for many years he worked as a hand on farms.

“I worked on dairy farms, I worked on pig farms, I worked on chicken farms. I worked on a heck of a lot of farms,” he said.

In time Leo reunited with his family who were now scattered across the map. He found his mother and in the years that she had left they celebrated a close relationship. Twenty years ago, in the days leading to her passing, she lovingly encouraged her son to remain independent, to remain free.

“Before my mom died she told me herself, she said to me, ‘I don’t want you to live with anybody at all. I want you to live all by yourself. First I told her I don’t know if I can do that. My mom said ‘you know you can do it and I know you can do it. I want you to try. I know it’s going to take you a while to get used to it but I’m sure you can do it’. I’ve been living by myself ever since. And I love living by myself.”

Leo’s sister, Jenny, ensured his well-being after their mother crossed the great divide. And then a few years later Melody came along.

*****

On December 9th, 2013 Ontario’s Premiere, Kathleen Wynne issued an apology, as set out by the settlement terms in the class-action lawsuit, to the survivors of regional centres that housed people with disabilities. In Wynne’s final remarks she said, “As a society, we seek to learn from the mistakes of the past. And that process continues. I know, Mr. Speaker, that we have more work to do. And so we will protect the memory of all those who have suffered, help tell their stories and ensure that the lessons of this time are not lost.”

Even in death there was no dignity for the residents of Huronia Regional Centre. The grounds cemetery where the number of dead that lay to ‘rest in peace’ is still unknown. In the 1970’s staff removed grave markers to build walkways and patio’s. In 1985 a chaplain made the horrifying discovery and collected as many tombstones that he could. Not knowing where they belonged the markers the were eventually laid out as a cement pad (pictured above). Fields of unmarked graves roll across the grounds of Huronia to this day. But- if that isn’t bad enough, just this week it has been discovered that at some time in the 1950’s tombstones were removed and a sewage pipe was run into the cemetery and a septic system was dug up in the cemetery for use by nearby institution houses.

One may wonder if Wynne’s statement was made tongue-in-cheek given that the provincial government provided a settlement to the measly tune of 35 million bucks for some 3,700 survivors and a promise that the Huronia cemetery would be maintained. The settlement effectively prevented the public airing of generations of physical, psychological and sexual abuse and neglect that occurred in the government run institutions.

The 65,000 documents collected through the class-action lawsuit which account the alleged abuses that happened at Huronia from police, witnesses and staff at the institution will only be available by filing a freedom-of-information request to the provincial government. Further, the province has the right to redact any material that it deems to infringe on privacy or that falls under one of the other numerous exceptions permitted for censorship.

Fortunately, there are many platforms where these difficult stories can be shared.

The advocacy work of Jim and his wife have advanced the preservation of about 10 survivor stories. These narratives will be archived in one location along with other stories as more people come forward to publicly share and document what they experienced while held at Huronia and other institutions like it.

There will be many people who read Leo’s story, and stories of other survivors, who may have never been aware of the atrocities committed against Canadians with developmental disabilities.

How could they?

For generations people with perceivable differences were isolated from mainstream society and as we’ve learned from Leo’s story, suffered inhumane crimes that were never reported or if reported, never legally pursued. It would be hopeful to say that we know better today, that people of all abilities are valued as equal human beings.

But we haven’t come too far.

One need only look to pre-natal testing for the presence of a third 21st chromosome – Down syndrome. Statistics show that of the women who do choose to undergo pre-screening for Down syndrome, 90% will abort if Trisomy 21 is detected. Eugenics –packaged as reproductive health services.

The last institution for people with developmental disabilities in Ontario closed 6 years ago. Have we become a more inclusive society? Or are we just warehousing people differently now?

Jim expresses concern for the well-being of older folks who have been released from the institutions. In Southern Ontario, self-advocates and supporters are struggling with accessible accommodations for seniors or people with physical limitations.

“One of the horrible things that we are starting to see happen with people who were in their 50’s and 60’s when they were released from the institutions is that they’re now at a point in their lives where they need accessible accommodation and a lot of group homes don’t have that,” explained Jim. “So they are being forced from group homes into long-term beds. It’s simply going from one bad institution to another bad institution at the end of their lives. It seems very unjust that these folks that had to live in institutions when they were young had to be put back into the same kind of environment that they grew up in.”

*****

Because of the extreme violence Leo suffered while in Huronia he could receive $42,000 for his misery. That works out to about $140 for every week he spent in the institution being beaten and experiencing, as well as witnessing, myriad other horrors –not to mention the uncounted years of residual trauma and suffering.

“Show her your hands Leo,” encouraged Melody gently. “It’s o.k. Leo,” she said as he tried to pull his hands into the sleeves of his leather jacket.

“His thumbs- he has to take arthritis medication. When it’s damp he can take up to six per day. When it’s not damp, he aches and he complains about it a lot. I truly believe he is in pain –his feet, his hands and his knees. I think a little is normal arthritis but I think a lot is due to the injuries he suffered to his hands and feet when he was in the institution,” she continued. “His hands use to bleed when they whipped him. The staff would use the soles and just whip him on his hands and they would bleed and blister. They would wake him up in the middle of the night to shovel snow and his hands and feet hurt from the cold. He wasn’t allowed to go back inside. He talks about working in the garden in the summer. I think he had heat stroke. He talks about being dizzy and thirsty. He was not allowed to go inside.”

The trusting relationship between Melody and Leo was an investment of time.

“Leo didn’t talk about the institution. We weren’t allowed to talk about it. The family wasn’t allowed to talk about it. It was just a given thing,” said Melody. “Then one day I went to Leo’s house. He finally gave me a key and I found him in the closet sleeping. I said ‘what are you doing’. He said ‘I sleep in the closet so the pigs can’t get me at night’.”

And that was how Leo began sharing his courageous story of survival and resilience with Melody.

Many years have passed since Melody discovered Leo slumbering upon the closet floor. Since that time Leo has attended various speaking engagements to tell others about his experiences in Huronia. He was particularly compelled to let First Nation communities know about what happened.

“Leo knew many First Nation people that were in these institutions,” said Melody.

Leo and his sister, Jeanette Fitton, revisiting Huronia Regional Centre. As part of the settlement, several days of an Open House were permitted to former residents and family members of residents. Perhaps an opportunity for closure, understanding and maybe a demonstration of defiance. These men and women are survivors of the grittiest kind.

Awaiting his settlement, Leo had a dream. With his due compensation he wanted to find a little place in the country and become a homeowner. Jenny, knowing how long these sorts of promises from the government can take to fulfil, wanted to make sure that her 76 year old little brother wouldn’t have to delay his hopes one moment longer. This spring, Jenny provided him with the means to purchase a snug little mobile home on the outskirts of Sault Ste. Marie- country living.

Landing just 1.7 km outside of the community para-bus boundaries means that on his fixed pension he is unable to afford the $15 rider fee and that Leo often walks into town to take care of business should an urgent matter arise. The other day he walked about 20 km to reach his bank in downtown Sault Ste. Marie and then walked 20 km back home.

“It was ok. I did it. I guess it would be nice if I had one of those battery operated bikes,” said Leo shrugging off the impressive trek. “Well, I got to go see those girls at the bank,” he said. “They would worry about me if I didn’t go in. I been goin’ there for years.”

He’s right. People would worry if he went under the radar for too long. The tellers at the bank, the barista’s at his favourite coffee hang out who spot him tea until his pension comes in at the end of the month, his bevvy of female co-workers at the Canadian Mental Health and his close ties with family and friends form the important daily networks that enrich his life.

But it’s not one way.

Leo and Melody have become family to one another, so much so that when Melody marries next month she has scheduled Leo for sittings during the wedding photo shoot. He just belongs in those family photos!

“Leo is probably the smartest person in my life and the most inspiring,” Melody emphatically stated. “He is so smart because he knew how to survive. And he is the most inspiring person in my life because most people couldn’t have gone through half of what he did and remain half as intact as he is.”

There is much to learn from a man like Leo. There are many truths that Leo can tell us that our government will not.

“Having heard stories from people like Leo, I understand now – and this is the disillusioning part, that there were a lot of bad people. And there were a lot of people that supported that bad system and did nothing about it. And the good people were few and far between,” shared Jim.

*****

His name is fitting. Leo, the lion, full of courage.

He was torn from his mother at 8 years old, separated from his siblings when he was 10 years old and then filed and recorded as a number in the Orillia Regional Hospital manifest.

He withstood heinous abuse. He was whipped. He was locked up. He was treated less than human. He escaped, many times. And though they would contain his body, they could not contain his brave heart.

He is a son, a brother, an uncle and a friend. He is a co-worker, a patron and a neighbour. He is a survivor, a teacher, an artist and a homeowner. He is a kind and gentle man.

And especially, and most remarkably, Leo is a man of undiminished spirit.

A commissioned work in progress. “I need a couple of fishermen in there,” said Leo sitting on his lazy boy in his new home -the home that HE owns.

Kindred spirits! Leo and Melody in front of Leo’s new digs. Congratulations on being a homeowner Leo!

![]() [1] http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/dshistory/reasons/index.aspx

[1] http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/dshistory/reasons/index.aspx

[2] ibid

[3] ibid

[4] http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/dshistory/reasons/eugenics.aspx

[5] ibid

[6] http://opseu323.tripod.com/hrchis.html

[7] http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/dshistory/firstInstitution/huronia.aspx

[8] http://www.institutionalsurvivors.com/

[9] ibid

4 Comments

A story that needed to be told and a wonderful tribute to Leo Gattie. Well done Steffanie.

I miss and love you Leo. Friends always Debbie Bell XOXOXO

What a great read. Unbelievable courage!

A very important story, thank you for telling it. There is one mistake though that I hope you will correct. “The last institution for people with developmental disabilities in Canada closed 6 years ago.” Ontario closed the last of their institutions in 2009 but unfortunately there are others that still exist in Canada. Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba still operate their large institutions for people with developmental disabilities. I don’t want people to think we have progressed farther than we actually have.